From Hazarajat to Wolverhampton, the incredible story of an Afghan torture and child labour survivor

“It was a dark, rainy evening when I arrived in the UK on 2 November 2004,” begins Rohullah Yakobi. Looking out from his small flat in Wolverhampton, a city in central England, where his family was crammed in, he could see children everywhere. Some were on scooters and mini-bikes, others were throwing firecrackers on what he later came to understand was Bonfire Night. It felt like a war zone. “Is this Britain?” he remembers thinking. “Or have we left one war zone for another?” It certainly wasn’t what he’d envisioned Britain to be.

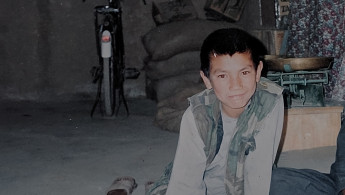

Draw a circle in the middle of a map of Afghanistan and you’ll find the Hazarajat. A mountainous region, it is the homeland of the Hazara people, who make up the majority of its population. Rohullah was born in a small village there, nestled between mountains, surrounded by rugged and unforgiving land. As a child, he never ventured far out of the village. There was a local school, a mosque, and that was what he assumed life to be.

His father was a member of one of the Mujahideen factions who fought against the Soviets and the Taliban. “Wearing a long beard, he was an imposing, tall and strong man,” Rohullah recalls. “I idolised him.” Their walls were lined with his rifles and every day before he left the house, his father could be found cleaning his beloved Makarov pistol.

In winter 1997, when Rohullah was 10, they had one of the heaviest snowfalls he remembers. The Hazarajat region was experiencing unprecedented temperatures, as well as a famine inflicted by a Taliban blockade.

“I don’t know anyone who wasn’t touched by the famine,” he says. His one-and-a-half-year-old brother was just one of the thousands who died of malnutrition that year across the Hazarajat.

A year later, the Taliban began their attacks on northern Afghanistan and the Hazarajat. They were heavily defeated in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif.

The Hazaras thought they were invincible, and let their guard down. But when the Taliban returned, they massacred thousands of civilians. Feeling the pressure, Rohullah’s father and his men fled the day before his village was invaded.

“We’d heard so much about these people,” he says. “I remember going to see who these ‘monsters’ were.” The Taliban wore sandals. With piercing eyes, they were dirtier and more rugged than them. “They were like aliens,” he adds.

|

|

At first, they didn’t touch or mistreat people; they were just strict. The first time Rohullah witnessed their violence was at the age of 11. Returning home from the local bazaar with his cousin, a car from the Taliban’s police force stopped in front of them. An officer called his cousin over and touched his chin, feeling for a beard.

“My cousin was 13,” explains Rohullah. “He’d barely hit puberty.” The man got out of his car, beat him with a baton and demanded: “Why have you shaved your beard?” To many, it can be impossible to imagine this type of violence. But Rohullah says that was the reality of life: “It completely dehumanises you.”

To many, it can be impossible to imagine this type of violence. But Rohullah says that was the reality of life: “It completely dehumanises you”

They soon started arresting people linked to his father. The day he was taken, Rohullah was returning from school wearing Hazara soldier trainers. A man drove by in a car and said: “Jump in.” He took his shoes and drove him to a newly established Taliban base. Rohullah recognised it instantly: “It was my father’s old base.”

That night, he remembers waking up to screaming from next door. In the morning, the Taliban commander called him into his office. His father’s old desk had been replaced by a mattress. The commander was making tea over a fire. Placing his spoon on the heat, he asked where his father was. “I didn’t know,” Rohullah replied.

The commander went ballistic, picking the spoon up and pressing it against Rohullah’s stomach. “I screamed.” The pain ended when the commander’s deputy soldiers asked him to let the child go.

He felt adrenaline running through his veins. “Where are my flip-flops?” he thought. Flustered, he grabbed a pair, put them on his hands, and ran home barefoot.

Fearing for his safety, Rohullah’s family sent him to stay with one of his uncles in Helmand’s Garmsir district, a Taliban heartland. That was the last time he saw his mother. Nobody he met in Garmsir was literate, but because he was, people became suspicious of him. Perhaps because they thought he was a spy.

Nobody he met in Garmsir was literate, but because he was, people became suspicious of him. Perhaps because they thought he was a spy

He was smuggled to Iran later that year, via Pakistan, with a fake passport in hand and aged only 12. Here he worked in factories and on building sites for two more years.

On 11 September 2001, Rohullah was walking to work when the news about the Twin Towers reached him. A farmer in a tractor was listening to the radio and he turned to him, saying: “Afghan boy, America has just attacked the Middle East.”

Rohullah remembers falling to his knees in euphoria. All his suppressed emotions exploded at once. He could finally go back to his village.

Unknown to him, his father had claimed asylum in Britain. It took some time for them to reconnect. The first time they spoke over the phone, he could almost smell him smoking. “I can hear in your voice how far the Taliban has kicked your ass,” his father said.

“They’ve kicked you so far, you’re in the UK,” Rohullah replied. They laughed and cried, and a few months later, he was reunited with his two siblings in Pakistan. Needing to prove they were related to their father, they had their DNA tested, acquired visas, and were finally able to leave for Britain.

Not long after arriving in Wolverhampton in 2004, Rohullah started an English language course. Alongside his struggles with the language, accents, and bullying, he was diagnosed with PTSD. So he dropped out of the course and began working at a factory.

|

|

Four years later, Rohullah got married and now has a son. This has bolstered him to finally improve his English. One of his then-colleagues was training to become an English teacher, so they made a deal: “I drive you to work every day, and you teach me English.”

Within two years, he was almost fluent. By then a British citizen, he applied for a philosophy, politics and economics degree at the Open University. This led Rohullah to write for the Human Security Centre, analysing Afghanistan’s conflict. People seemed interested in his commentary, and he soon began speaking at big conferences, like the Open University Charter Day in 2017, where he met David Attenborough.

Rohullah returned to Afghanistan in 2018, but it was too dangerous to visit his village. “My face is too well-known,” he tells The New Arab from his home in Wolverhampton. “But I’d love to go back one day.”

Olivia is a freelance journalist and an aspiring Middle East correspondent finishing her journalism degree at City, University of London.

Follow her on Twitter: @oliviarafferty6

![Minnesota Tim Walz is working to court Muslim voters. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2169747529.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=b63Wif2V)