'Talibanisation of education': Why did Afghanistan's government try to ban schoolgirls from singing?

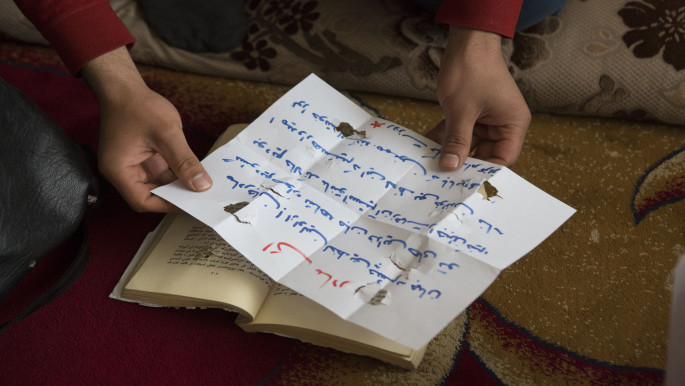

Leaked to the local media in early February, the letter also declared a ban on male instructors teaching music to girls above the age of 12.

A powerful social media campaign forced the education ministry to backtrack on the move in an act of collective resistance, which showed that the Afghan civil society would not allow a regression to Taliban-era policies, where women already suffered immensely under a brutal, state-enforced misogynism.

In the wake of the public outrage, Najiba Arian, the education ministry's spokesman, issued a statement claiming that the letter issued by Kabul's local education department did not reflect the official stance of the ministry.

In the statement she said the ministry was "committed to supporting the right to education and the right of all male and female students to participate in cultural, artistic and sports programmes" and that it did not want "to restrict the legal and educational rights of students".

|

A powerful social media campaign forced the education ministry to backtrack on the move in an act of collective resistance, which showed that the Afghan civil society would not allow a regression to Taliban-era policies, where women already suffered immensely under a brutal, state-enforced misogynism |  |

A subsequent memo appeared to clear up that misunderstanding by then banning both girls and boys from singing.

However, even before that, the ministry had gone on record defending its nationwide ban on schoolgirls on the grounds that "parents had asked for daughters to be excluded from public performances, as some students themselves complained that the infrequent commitments hindered their studies," according to Reuters.

Ali Latifi, a journalist who is based in Kabul, told The New Arab that the saga exemplified the Afghan government's incompetence.

"The director of education in Kabul does not outrank the minister of education. They have to report to the minister of education, who must then approve what they say. People are confused. If the ban really happened, then it shows more government dysfunction," he said.

|

|

| Read also: Assassination campaign targets intellectuals and human rights defenders as violence across Afghanistan escalates |

Adding to the perplexity of the affair is the physical proximity between Kabul's directorate and the education ministry, according to Latifi.

"Miscommunication would be excusable if the decree came from faraway provincial authorities, where the Islamic madrassah substitutes for the absence of government-run schools," he explained.

But was the ban a momentary collapse in the Education Ministry's chain of command, or did it augur larger sociopolitical shifts looming on Afghanistan's horizon?

At present, Afghanistan's international stakeholders (some of whom invaded the country to topple the Taliban) are pushing for a new interim government which shares power with the Taliban.

Kabul's administration, which has indicated it is opposed such a settlement, blames the militant group for spike in killings targeting prominent Afghan women – including assassination of female judges, journalists, and rights activists.

Furthermore, women and girls in the country are afraid that any deal with the Taliban will roll back decades of progress in women's rights. It is no surprise that the ban on schoolgirls singing was met with outrage.

|

Women and girls in the country are afraid that any deal with the Taliban will roll back decades of progress in women's rights. It is no surprise that the ban on schoolgirls singing was met with outrage |  |

Rangina Hamidi and the Afghan Education Ministry

One figure with a central role in the events that unfolded is Afghanistan's Acting Education Minister, Rangina Hamidi. A caretaker minister who is yet to be approved by parliament, Rangina appears to have long advocated for women's rights in the war-torn country, setting up the first women's private enterprise in the southern province of Kandahar.

Lately however, Hamidi has promoted policy maneuverers which seem to appease those parliamentarians whose very vision for Afghan society is similar to the Taliban's.

According to Saber Ibrahimi, a non-resident scholar at NYU's centre on international cooperation, hardline lawmakers, likely irked by the minister backtracking on the ban, have a far-reaching presence in the Afghan political stage.

"There is concern about hardline elements, not only within the ministry of education but in the entire cabinet," Ibrahimi tells The New Arab.

"The Taliban are pushing for a more conservative society; the government is trying to prove itself as Islamic as the Taliban; there are hardliners within the government and in the parliament, and there is also the broader conservative society that the ministry is trying to accommodate," Ibrahimi explained.

The minister's attempts to accommodate the conservative swathes of Afghanistan's political and social body have been fraught.

When she addressed parliament in December, she appeared to struggle to recite a hadith – a saying of Prophet Muhammad – while displaying a fragile command of formal spoken Dari – one of two national languages spoken in Afghanistan.

Around that time, one of Hamidi's other announcements garnered bad press – a proposal that all children should receive primary education in mosques. This avowed aim was to bridge an apparent gap between religion and education.

The policy proposal raised eyebrows with both domestic and international observers, given that some madrassahs which educate children in lieu of schools are known for poor regulation and encouraging extremist ideas.

In response to a backlash which came then, the education ministry insisted the move would widen education to those who did not have access to schools.

|

The Taliban are pushing for a more conservative society; the government is trying to prove itself as Islamic as the Taliban; there are hardliners within the government and in the parliament, and there is also the broader conservative society that the ministry is trying to accommodate |  |

#IAmMySong

Dr Ahmad Sarmast, the head of the Afghanistan National Music Institute and a towering figure in music education in Afghanistan, said the ban of schoolgirls above the age of 12 singing at public events sounded alarm bells. He believed that "more exclusion would come regarding women, arts and culture".

Twitter Post

|

Dr Sarmast was a key figure in a social media campaign protesting the ban. Based on the hashtag #IAmMySong, it featured Afghan woman and girls uploading short video extracts of themselves singing. The campaign gained traction across Afghanistan, with a petition reportedly gaining hundreds of thousands of signatures in different provinces.

Dr Sarmast, who established Afghanistan's first youth orchestra and oversees a music institution which is seeing more girls enrol than boys, was forthright in his criticism of the Afghanistan Ministry of Education, in comments to The New Arab

"The ministry appears to be paving the way for the Taliban and for the start of 'Talibanisation' of the educational system in Afghanistan. Its job is to ensure gender equality and assist in the empowerment of women. In all the legislation and policies of the ministry, they promise these things as well as equal opportunities in arts, culture and sport," he said.

"The ban was a shock because it came at a time when we're talking about the future of Afghanistan – at a time when Afghanistan is talking with the Taliban, and the government is representing itself as the advocate of the Republic and for the preservation of the constitution."

Dr Sarmast is unconvinced by the ministry's response and says a letter should be issued explicitly rejecting the ban because according to him "there are many figures in education in Afghanistan, including school principals, with sympathy for the Taliban or Taliban-like mindsets that would use the letter as guidance."

|

There are many figures in education in Afghanistan, including school principals, with sympathy for the Taliban or Taliban-like mindsets that would use the letter as guidance |  |

Power-sharing with the Taliban

Afghanistan is at a crucial political juncture. US President Joe Biden indicated that the May 1 deadline for the withdrawing US troops, set by his predecessor, would likely be unmet.

The Taliban say there will be "consequences" if this happens. While they have largely stuck to their promise not to attack foreign forces under an agreement with the Trump administration, they have stepped up their war on the government.

Fighting has raged amid negotiations between the warring sides, launched in September and billed as landmark for the country's future. Yet they have failed to achieve any real progress.

Both Biden and the NATO's chief have said that any troop withdrawal is tied to success in intra-Afghan talks. With a gathering in Moscow of Afghan stakeholders last week failing again to break that deadlock, hopes are now pinned on a large conference in Turkey next month.

US, Russia, and other international powers want to see some form of transitional government take hold in Afghanistan, which involves power-sharing with the Taliban.

Analysts believe the Taliban will not easily accept a power-sharing agreement in an interim government, given it would effectively rule out the possibility of them restoring their ideal of an Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan.

Women, singing and the future of Afghanistan

When the Taliban ruled Afghanistan, their restrictions on girl's and women's dress, work and education hit hardest in Kabul. The city had been more Westernised than others and had the highest proportion of educated Afghans and intellectuals, according to Professor John Baily, a renowned ethnomusicologist who spent decades in Afghanistan.

Reflecting on music censorship under the Taliban after their rule in 2004, Professor Bailey contributed a chapter to a book titled Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today. He notes that the the Taliban banned all musical activity other than certain forms of unaccompanied religious recitation and singing, known as Tarana.

Ironically, a nationalist form of Tarana sung by schoolchildren would have been a target of the ban in the leaked letter by Kabul's education directorate.

|

When the Taliban ruled Afghanistan, their restrictions on girl's and women's dress, work and education hit hardest in Kabul. The city had been more Westernised than others and had the highest proportion of educated Afghans and intellectuals |  |

Professor Bailey goes on to discuss forms of censorship in the period preceding the Taliban, the time of mujahideen rule. In Herat, pigeon flying and flying kites were banned on the grounds that it could lead to men spying on the courtyards of their neighbour's houses. Authorities were honest about why they stifled recreation and entertainment.

Immediately after the Taliban were toppled, the topic of women singing became the subject of intense wrangling between radio and television organisations, Professor Bailey adds.

The reasons given included the fears that the ban would give the Taliban an easy way to stir up trouble, there were no more competent female singers in Kabul, or that it would leave women vulnerable to attacks.

In 2019 Zahra Elham won Afghan Star – a sensational nationwide singing competition akin to X Factor and was a victory that came after the show counted 13 male winners since its inception fourteen years ago.

It was also a statement that proved artistic expression was a critical part of women's hard-fought rights and freedoms since the days of the Taliban.

Today, it is clear why Afghanistan's Ministry of Education had to change its narrative on banning schoolgirls from singing. Afghan women and girls will not easily allow the powers that be to encroach on their rights and freedoms once again.

Kamal Afzali is a journalist at The New Arab.

Follow him on Twitter at @KNIAfzali

![Afghan schoolgirls [Getty] Afghan schoolgirls [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_345x195/public/media/images/A9D672C9-DFFD-4FCD-B57F-65DEBD45D39C.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=1EFsoqKu)

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News