By helping Israel, Oppenheimer sparked a regional nuclear arms race

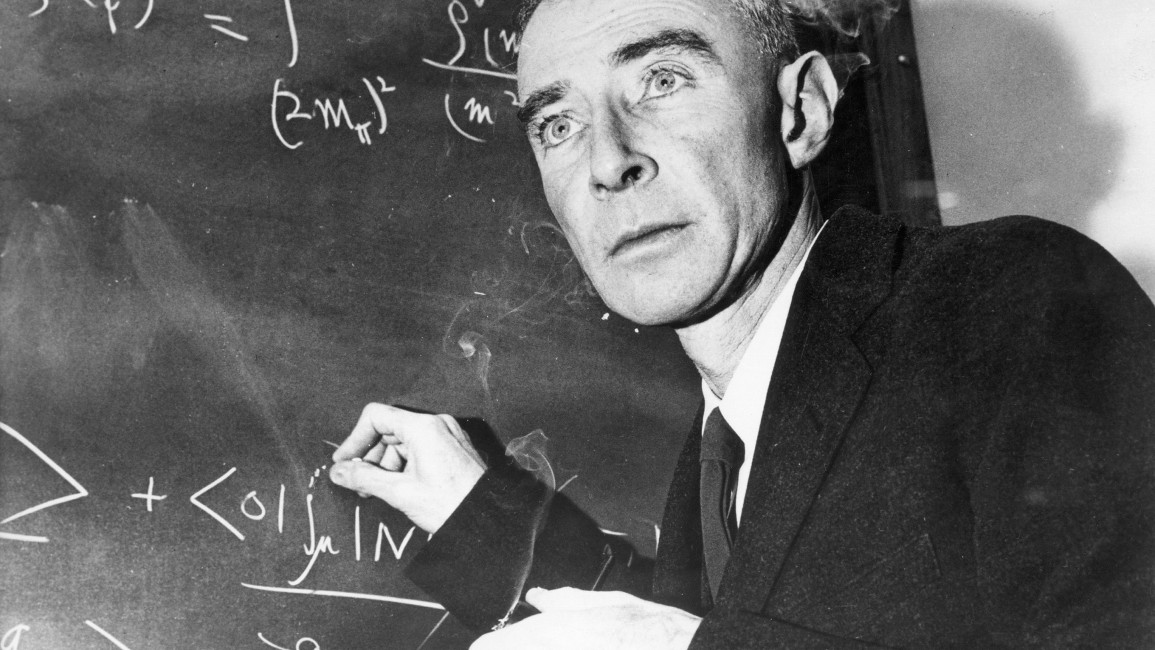

Oppenheimer is a three-hour biopic of American theoretical physicist and father of the atom bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Throughout, director Christopher Nolan moves back and forth in time to either side of the 1945 Hiroshima & Nagasaki mushroom clouds.

Exploring Oppenheimer’s origins, struggles, and fate, the film may not measure up against Nolan’s other works, such as Dunkirk (2017) and Interstellar (2014), in terms of explosiveness and visual dynamism.

However, it excels at gauging the fluid realm between science and morality. It seeks to provide a clue about Oppenheimer’s belief system, which biographers continue to grapple with, and shed light on his ethical dilemma.

In doing so, Nolan rehabilitates the image of America’s Prometheus and reintroduces him as a tragic moral hero and historic icon.

"Despite his guilty conscience, Oppenheimer allegedly never regretted building the bomb or, as a matter of principle, opposed deploying the weapon against imperial Japan. In fact, he explicitly lamented that the weapon had not been developed in time to be used against Nazi Germany"

The first-ever explosion of the atomic bomb in July 1945 was in the New Mexico desert, exposing tens of thousands of mostly Latino and Native people to extreme levels of radiation without warning, resulting in generations of cancer.

After the blast, Oppenheimer - then the director of the Manhattan Project - is said to have whispered to himself a line from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita that has come to define his public image: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Mere weeks later, an American B-29 bomber named the Enola Gay broke the morning silence in the sunny sky over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. For the unassuming population who lifted their heads to peer at the foreign aeroplane, it was an inescapable moment of oblivion.

What started as a whistling sound soon turned into a dazzling flash. Then came the heat and wind that vaporised people and tore buildings to dust.

Before the Japanese had woken up from the shock, another atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. A quarter of a million Japanese lives were lost to the technology Robert Oppenheimer and colleagues developed at Los Alamos.

78 years since the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the only way to deliver justice to victims is through global nuclear disarmament, argues Farrah Koutteineh. Especially as the Oppenheimer film fails to hold US accountable ⬇ https://t.co/ee4wCqz8IC

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) August 7, 2023

Nolan presents Oppenheimer as a troubled man, though he does not spend much time exploring the depth of his trepidations.

The presentation, nonetheless, serves to highlight the physicist’s sense of guilt, allowing the plot to evolve to show Oppenheimer’s efforts to atone for his terrible brainchild, in a fashion similar to the theme of atonement in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

After the war, Oppenheimer would become an advocate for nuclear peace. He sat with President Truman to talk about international control of nuclear weapons.

“I feel I have blood on my hands,” he reportedly said. The angry president called him a ‘crybaby scientist’ and did not want to see him again.

Despite his guilty conscience, Oppenheimer allegedly never regretted building the bomb or, as a matter of principle, opposed deploying the weapon against imperial Japan. In fact, he explicitly lamented that the weapon had not been developed in time to be used against Nazi Germany. He never held himself publicly accountable for the death of hundreds of thousands of people.

This moral ambiguity is fairly common in science and happens in scenarios where the legitimate and illegitimate overlap, thus leading to different ethical assessments based on the stakeholders and potential outcomes.

Controversial consequences, in other words, are rationalised in the name of the collective good or self-interests. Those that defend the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki argue that this ultimately shortened the war in the Pacific and potentially saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Nolan tackles this particular issue but stops short of exploring the full extent of Oppenheimer’s moral ambiguity, certainly regarding his involvement in developing Israel’s nuclear capabilities.

Despite his own discomfort with his Jewishness and alleged disinterest in political Zionism, Oppenheimer was a supporter of Israel. Declassified documents in Israel’s state archives suggest that he may have played a role in developing Israel’s nuclear programme.

"Israel needed a qualitative military edge to counterbalance the Arab quantitative advantage, which would allegedly only be used 'defensively' in emergency situations. An Israeli bomb, they believed, might force the Arabs to accept Israel’s existence and seek to make peace with it"

In 1947, he met with Haim Weizman - Russian-born Zionist leader and Israel’s first president - to discuss Israel’s nuclear capacity. Five years later, Oppenheimer and Edward Teller - his colleague at the Manhattan Project and, later, an adversary - met with Ben-Gurion to explore the best scenarios to manage Israel’s plutonium reserves.

Ben-Gurion admired and praised Oppenheimer, and the latter, reportedly, emphasised to the Israeli prime minister that Israel needed to develop nuclear capabilities against the threat presented by Egyptian-Russian relations.

Israeli leaders saw that the ‘new state’ was existentially threatened by its Arab neighbours, coupled with another belief stemming from the Holocaust that no one but Israel would come to the Jews’ rescue.

Israel needed a qualitative military edge to counterbalance the Arab quantitative advantage, which would allegedly only be used ‘defensively’ in emergency situations. An Israeli bomb, they believed, might force the Arabs to accept Israel’s existence and seek to make peace with it.

Israel reached a secret agreement with France in 1957 to help install a plutonium-based facility in Dimona, Negev. It is estimated that today Tel Aviv has a stockpile of approximately 90 nuclear warheads, though the country never confirmed nor denied its possession of nuclear weapons.

This moralistic logic for Israel’s programme accounts for the mainstream Western view today that deems Israel's nukes morally and historically defensible, in a way that an Iranian or a Pakistani programme or any others in the region are not.

The logic has long ensured Israel had a nuclear monopoly and provided it with political and diplomatic cover to target any regional nuclear attempts, as it did against Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2006.

Regions typically have several adjacent nuclear-armed states or none. Israel, however, is a historical anomaly in being the only nuclear power in an immediate region that is nuclear weapons-free.

Save for the fact Israel has been uniquely belligerent thus raising the nuclear risks and impunity, its possession of nuclear warheads has, in fact, upped the stakes of regional nuclear armament.

"One way or another, Oppenheimer's role in developing Israel's programme helped trigger a nuclear chain reaction in the Middle East"

Indeed, an Iranian bomb will be no small matter for Tel Aviv. But, ironically, Israel’s nuclear stockpile itself may have been the primary drive behind Iran’s programme in the first place. In the same sense, an Iranian bomb would encourage Saudi Arabia to obtain nuclear capabilities.

It is hard to speculate what Oppenheimer would have thought of Israel’s nuclear posture today, or whether Israeli PM Golda Meir’s decision to ready 13 atomic bombs to use against Egypt during the 1973 Yom Kippur War would have been ‘morally comprehensible.’

But one way or another, Oppenheimer’s role in developing Israel’s programme helped trigger a nuclear chain reaction in the Middle East.

He effectively, albeit not solely, put in high gear the very nuclear proliferation that he claimed to have feared and campaigned against after World War II.

Dr Emad Moussa is a Palestinian-British researcher and writer specialising in the political psychology of intergroup and conflict dynamics, focusing on MENA with a special interest in Israel/Palestine. He has a background in human rights and journalism, and is currently a frequent contributor to multiple academic and media outlets, in addition to being a consultant for a US-based think tank.

Follow him on Twitter: @emadmoussa

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.