The Good Friday Agreement: 25 years of deflecting from British imperialism

This week will see global leaders both past and present, from Biden to Sunak, to Blair and the Clintons, descending upon Belfast to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.

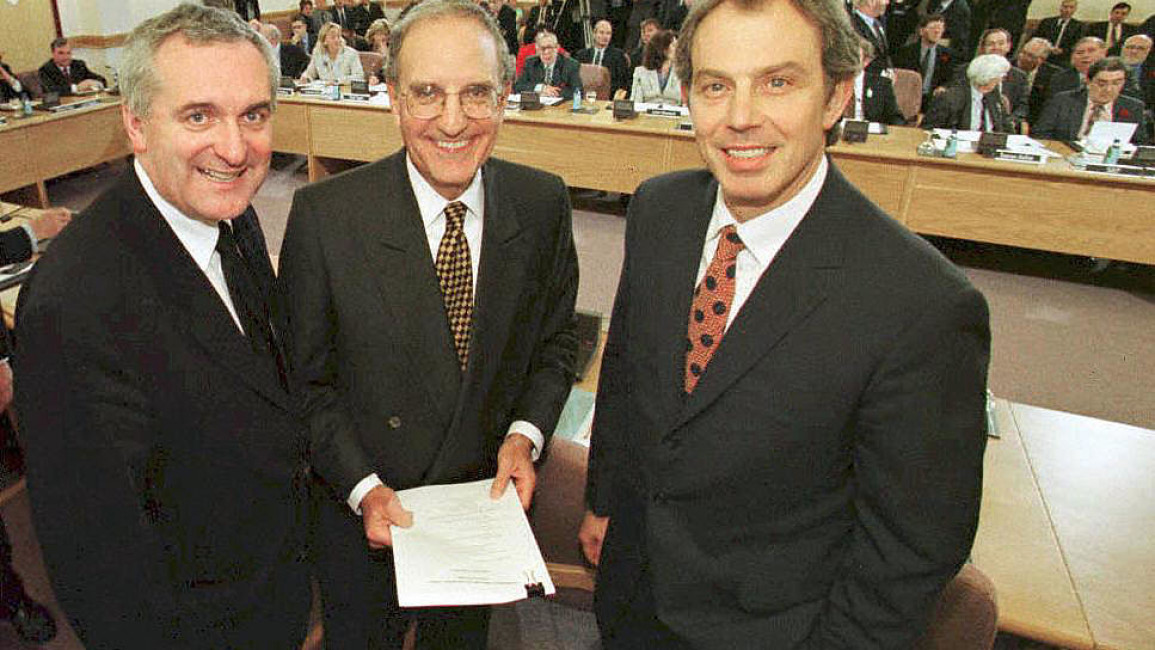

Indeed the 10 April 1998 was a landmark moment in Irish history when two agreements were signed – one between the British and Irish governments, and the other between the ‘Northern Irish’ political parties. It affirmed that the North of Ireland would constitutionally remain a part of the UK, outlined a power sharing assembly to make up a devolved government of both Irish-Republican and British-Unionist parties, promised police reform, granted the early release of political prisoners, and called for the disarmament of paramilitary groups, which included the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and others.

Also referred to as the Belfast Agreement, it was signed by a select few political leaders from the UK to the Republic of Ireland, aided by the Clinton administration, and was voted on by the public in both the North & South in an all-Ireland referendum.

''An obvious and expected absence in the reportage of the Good Friday Agreement’s 25th anniversary, is its unwritten aim: ensuring the longevity of British imperialism in Ireland. Indeed, continuing to distort the history of 800 years of British oppression of Ireland with a fabricated narrative of sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants, would pacify what was becoming an uncontainable issue: Irish resistance.''

It came after over 30 years of intensified armed Irish-republican struggle against British military occupation and its partition of the North of Ireland, often referred to as ‘The Troubles’, which claimed the lives of over 3,600 people.

As global political leaders arrive in Belfast this week to mark the agreement's quarter centenary, the vast majority of the population across the North of Ireland who live in deprived, impoverished and segregated communities, who are victim to corrupt sectarian policing, and a mental health crisis, are not joining in the celebrations.

This is largely because decades on, the vast majority of points that were outlined in the agreement have either failed in practice, or have remained empty words on paper.

One of the main aims – outlining power-sharing of its devolved government between Unionist and Republican parties – has proven to be a colossal failure. The North’s executive, which is the sitting government at the time, presides over the local Assembly (Stormont) in Belfast. However, Stormont has been in a state of collapse for almost half of its existence. In fact, if you add up the number of party boycotts, political stalemates and executive dissolutions, the North has effectively been without a functioning government for 10 entire years since 1998.

One of the most contentious parts of the agreement was the promise of police reform. For decades, the police force in the North, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), was deeply sectarian, consisted mostly of Protestant officers who colluded with British intelligence and Protestant/loyalist paramilitary groups in carrying out political assassinations and subjugated the Irish-Catholic population. However, the agreement seems to have merely rebranded the RUC into today’s Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI); with many RUC officers continuing to serve.

According to recent statistics published by the PSNI, their broader religious make-up comprises 67% perceived as Protestant and 32% perceived as Catholic, and its elite Special Branch, remains almost 80% Protestant, despite the agreement’s promise to achieve 50/50 representation.

Discrimination against the Irish/Catholic community is confirmed by the PSNI’s own statistics which state they are twice as likely to arrest and charge a Catholic in the North than a Protestant. Between 2016 to 2020 they arrested 57,000 Catholics compared to 31,000 Protestants. Of those that they then charged, 27,000 were Catholic’ and 15,000 were Protestant.

In reality, since the often referred to ‘peace agreement’ which has historically been praised for supposedly ‘bringing two sides together’, the North of Ireland has only become more segregated. For example, there are more segregation walls or “peace walls” – 116 of them to be precise – dividing Catholic and Protestant communities today than there were at any point before the agreement. Furthermore, 93% of all schools remain segregated by religion, and 90% of all social housing is also still segregated.

One of the vital points of the agreement was for the North of Ireland to constitutionally remain part of the UK, and since 1998 it has remained the poorest part of it. Over 330,000 people are living in abject poverty, 1 in 4 children are living on the poverty line and there is an ever increasing homeless population. To make matters worse, privatisation is expanding faster across the North of Ireland than anywhere else in the UK, with Westminster’s neoliberal policies forcing the shutdown of hospitals, healthcare centres and vital public services.

Another undoubtable failure of the agreement was the absence of any solution to address the decades of trauma people in the North experienced. Statistics reveal that thousands more people have died by suicide after the Troubles, than died during, and there’s been an estimated 5748 deaths recorded as suicide since 1988. A veritable and persisting mental health emergency.

The quote on Free Derry corner says all that needs to be said. The counter revolutionary Good Friday Agreement is not to be celebrated. Whilst it also impounded misery on the working class it also solidified partition as a continuation of the 1921 counter revolutionary treaty. pic.twitter.com/JXwv99GXUi

— Paul 🇮🇹🇦🇷 (@L191719171916) April 7, 2023

Finally, an obvious and expected absence in the reportage of the Good Friday Agreement’s 25th anniversary, is its unwritten aim: ensuring the longevity of British imperialism in Ireland. Indeed, continuing to distort the history of 800 years of British oppression of Ireland with a fabricated narrative of sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants, would pacify what was becoming an uncontainable issue: Irish resistance.

Historically, radical class unity had long existed between Catholics and Protestants in Ireland, most notably the 1932 strikes, where over 60,000 workers from both communities fought for fair pay and better living conditions. The divides only developed and deepened through the concerted efforts of British forces.

Ultimately the agreement was fundamental in Britain’s suppression of Irish resistance. This was achieved through its policy of disarming paramilitary groups (which were predominantly Irish resistance groups) and the renaming of the North’s police force, who didn’t adopt any of the changes stated but continue to work alongside British intelligence in undermining Irish republican activity aimed towards ending British presence.

It couldn’t be clearer that this agreement was only crafted and signed to prolong British imperialist interests in Ireland.

As world leaders flock to Belfast regurgitating the same disingenuous sentiment that the Good Friday Agreement brought an end to violence, all the facts prove otherwise. Violent segregation, a corrupt sectarian police force, suicide, homelessness and abject poverty all persist for the people of the North, from both sides of the ‘peace walls’. They do not reap any benefit from the Good Friday Agreement, instead they are pawns in Britain’s long game of imperialism on the Island.

Farrah Koutteineh is head of Public & Legal Relations at the London-based Palestinian Return Centre, and is also the founder of KEY48 - a voluntary collective calling for the immediate right of return of over 7.2 million Palestinian refugees.

Paul McGoldrick is a member of the Robert Emmet 1916 Society who are based in Co. Fermanagh, Ireland. They are a socialist republican pressure group who are involved in grassroots leftwing activism. Paul is also a mental health campaigner involved in various community lead initiatives aimed at tackling social deprivation and inequality.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News