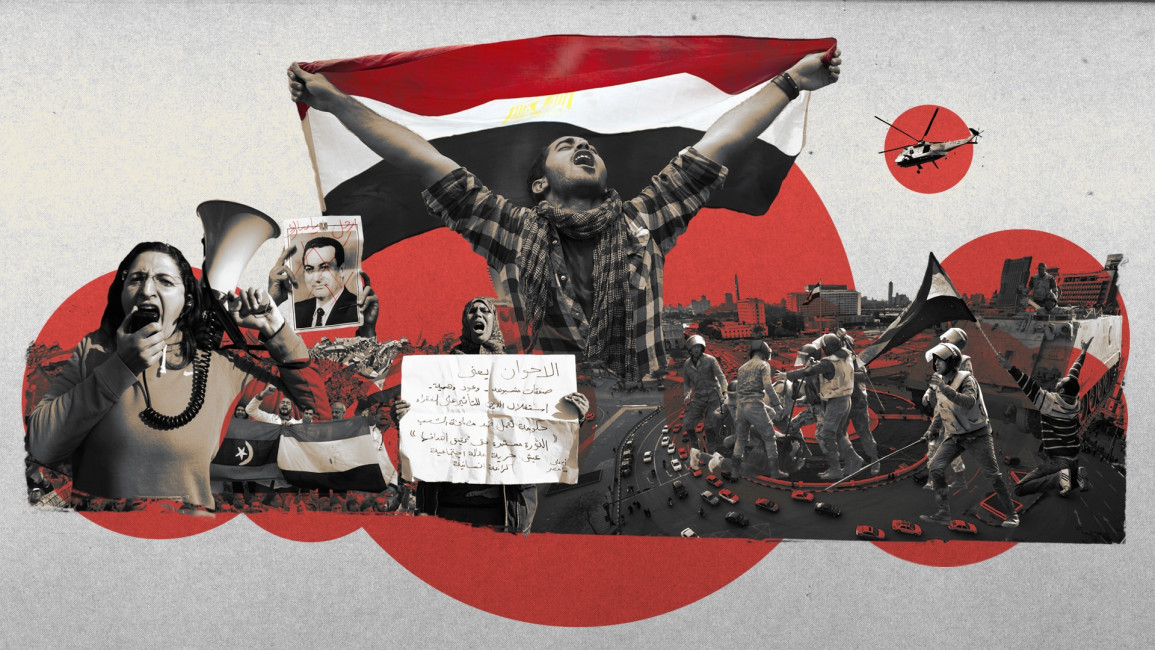

A decade of Arab protest caps a century of erratic statehood: Part II

Taking stock of an unprecedented decade

The balance sheet is mixed. Tunisia and Sudan have achieved democracy or a transition to it, but both are in fragile condition. Yemen, Syria, Libya, and Iraq remain mired in domestic or regional wars. Monarchies such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, and Morocco and Jordan to a lesser extent, all either prohibit public protest or allow only symbolic gestures that do not threaten the power structure. Foreign powers are frequently involved in the wars and in bolstering Arab autocrats.

Read more: The price of Arab resilience

The most important countries to monitor today are where the 2019-20 protests are certain to resume when conditions permit - Algeria, Lebanon, Sudan, and Iraq. Their uprisings all elicited limited state concessions without any real change in the exercise of power; only Sudan's protests forced the military regime that ousted President Omar Hassan Bashir to negotiate a gradual transition to a democratic system. That arrangement is very fragile, with the civilian and military wings of the transitional authority often at odds (such as on normalisation with Israel) and the economy remains in dire straits.

The stalemate and pause see activists reassessing their tactics and strategy, with many advocating to organise at the grassroots and nationally to create political parties or movements that can contest future elections. The street protests and disruptions of normal life clearly have not caused regimes to cede power, and foreign parties are not stepping in to save collapsing economies. Most Arab elites and protesters realise that they are on their own, because the Arab region as a whole, for the most part, has lost its strategic relevance to foreign powers. Those powers that do intervene - like Russia in Syria - do so to maintain the autocratic order that serves their strategic interests.

|

That sense of agency and change-through-political action never existed on a wide scale before, and now permeates hundreds of millions of ordinary men and women of all ages |  |

The least visible but perhaps most significant change of the past decade that might define the future of political rule in Arab societies is the realization by individuals and masses alike that they are not helpless in the face of their ruling regimes, but rather that they can organise and protest and try to define their own future. That sense of agency and change-through-political action never existed on a wide scale before, and now permeates hundreds of millions of ordinary men and women of all ages. When it is mobilised again, it is likely to have more impact than it has this decade.

The lessons of an uprising on standby

The main lessons seem to be about the balance of power among the two forces that confront each other - the protesters who spontaneously took to the streets to remove their governments but did not master the keys to success, and the power elite that has ruled for decades and will fight to remain in place, even if it governs shattered societies like Syria, Yemen, and Libya. The 2010-20 decade is the latest and most robust, but not the final stage of Arab transitions to democracy and stability.

The confrontations will resume post-Covid because all the underlying conditions of citizen despair that prompted the uprisings continue to deteriorate. As citizen well-being plummets and poverty and vulnerability spread to over 70 percent of the population, confidence in governments vanishes and popular support for the uprisings increases.

These trends are repeatedly confirmed by opinion polls. The most recent regional survey, by the Doha-based Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, showed that household income is insufficient for nearly 75 percent of families. One in five Arabs wants to emigrate, and almost one in every three 18-34-year-olds wants to leave for good. About half the people view government performance negatively, over 90 percent see corruption as prevalent, and less than one-third feel that the rule of law is applied equally to all citizens.

|

The confrontations will resume post-Covid, because all the underlying conditions of citizen despair that prompted the uprisings continue to deteriorate |  |

These realities explain why 58 percent of the entire region view the uprisings positively, and in the four countries where the protests continue the public's support ranges from 67 to 82 percent. The widespread desire for change only intensifies as economic conditions deteriorate and governments seem uncaring about their citizens' suffering. Citizen agitation for deep change will persist, though it is not clear today in what form, due to the limited impact of the last decade's activism.

We should view the revolutionary uprisings in Arab lands as dramatic elements in the state-building process that started a century ago, but never solidified its results in most cases because ordinary citizens never had an opportunity to shape decisions about national values or policies. The uprisings have sent the message that citizens need material well-being, opportunity, and security, as well as intangibles like dignity, respect, voice, and identity. They will continue to do that in new ways, with much greater awareness of how to confront stubborn state power.

As the Arab system of states now enters its second century of state-building, anxious and determined citizens who battled for a better life in the 2010-20 decade will keep trying to make sure that they finally exercise their right to, and participate in, their national self-determination.

Rami G. Khouri is Director of Global Engagement and senior public policy fellow at the American University of Beirut, and a non-resident senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Follow him on Twitter: @ramikhouri

Have questions or comments? Email us at editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.