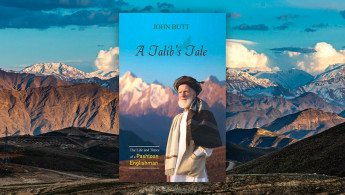

A Talib's tale of hippies, Islam and adventure: The Life and Times of a Pashtoon Englishman

Why would an English man travel to a foreign land and accept Islam? In A Talib’s Tale, Islamic scholar and journalist John Muhammad Butt takes the reader through the journey of his life and travels over five decades from Britain to India, Afghanistan, Pakistan and back to the UK.

The memoir offers a recollection of his extraordinary life as one of the many 1960s truth seekers who travelled to the East and joined the “hippie trail” in India.

This eventually led to his conversion, and becoming a student of Islam. He holds the unique distinction of being the only Western graduate of the famous Darul-Uloom Deoband, Islamic Seminary based in North India and also discusses his life in Afghanistan and career transition into media journalism.

"I had no particular attraction to or even knowledge of Islam until I arrived among the Pashtoons of the North-West Fronter Province of Pakistan. The Pashtoons I was with really felt they had something of immeasurable worth — Islam — to give to the world"

What drew you to the “hippie trail” in India during the late 1960s?

Well, I was very much part of the hippie culture, determined to extract more out of life than the usual materialistic goals that people work for. I have to be honest and admit that I probably had sufficient financial security from my family side to give me the luxury to be able to think over and above mundane, material objectives.

However, that did not figure into my consideration at that time. I simply felt there was more to life than what Western culture had to offer. The hippie counterculture was my escape route from the West.

How did you convert?

I had no particular attraction to or even knowledge of Islam until I arrived among the Pashtoons of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan. The Pashtoons I was with really felt they had something of immeasurable worth — Islam — to give to the world.

They let us hippies know about Islam — in both their words and their kind and generous actions. This led to a spate of conversions in the summer of 1970. This increased the pressure on others to convert.

I initially resisted this pressure but then something happened that tipped me over the line. I have mentioned that event in A Talib’s Tale. I had better not steal all my own thunder! Best to leave some things in reserve, for people to read about in the book.

Why did you decide to become a Talib of Islam?

I was always keen on classical education. Somehow, I missed out on that during my education at a Roman Catholic Jesuit public school in England. I just resented even being at that school, let alone immersing myself in acquiring learning. I could not fulfil my potential in that environment. Maybe Allah was just saving me up for an Arabic and Persian-based Islamic classical education, instead of a Western Latin and Greek one. In retrospect, of course, it would have been good to have both but if one has to choose, I am happy with the choice I made.

Which scholars influenced your learning and why?

I was lucky in that regard. From the beginning, the scholars who taught me were all students and followers of the great Sheikh’al-Quran of the Pashtoons, Maulana Mohammad Tahir. He passed away in 1986. Sheikh’al-Quran’s motto was ‘that I should recite the Quran’. He lived to teach the Book of Allah.

I had the good fortune of studying under four of his leading students, along with completing the entire Quran — of course with full meaning and explanation — twice with the Sheikh himself. The older generation of my teachers — the Sheikh himself and one other of their number — had themselves studied in Delhi and in Deoband prior to the Partition of India in 1947 that led to the creation of Pakistan.

How did you prepare the material for this memoir-did you keep a daily journal or did you work to complete it within a timescale?

I never kept any diary or journal. I guess the memory also acts as a kind of filter and important things — or what one feels is important — remain there. People say what an amazing memory I must have to remember all that stuff. I’m sure they can also remember a whole lot if they only try.

"I see media work, not so much as a transition from Islamic scholarship, but as an extension of Islamic scholarship. This does not only apply to storytelling with a moral, it also applies to more mainstream journalism"

My memoir was first published by Penguin in India, in March 2020 – right at the beginning of the COVID lockdown. After we came out of lockdown Kube published an international version. It was not a book I particularly wanted to write, but more a book I felt I had to write, considering all the insights into Islam, Afghanistan, and Pashtoon life I have gained over the years. I felt I had a duty to share those insights and experiences with a wider audience.

After living for so long in the region-what drew you back to England in the 1990s?

I launched my media career working on a popular and influential newspaper based in Peshawar, the Frontier Post. I loved journalism and took to it like a fish to water. However, to progress as a journalist, I felt I had to go to the UK. I did so in 1991 and was lucky enough to join the BBC. The BBC did not waste much time in sending me back to Peshawar.

|

Why did you transition from Islamic scholarship to media journalism and how was the Afghan version of the Archers received there?

Yes, my posting for the BBC in Peshawar was to set up an ‘Archers for Afghanistan’ in 1993, the Archers being a radio drama series on BBC Radio 4 initially set up to encourage post-World War II reconstruction. No such luck in Afghanistan where the war situation dragged on and on! Still, the ‘storytelling with a moral’ approach to addressing Afghanistan’s problems went down very well in Afghanistan. It is absolutely in line with the storytelling tradition in Afghanistan. People are being entertained and at the same time being given ideas as to how to improve their lives.

For that reason, I see media work, not so much as a transition from Islamic scholarship, but as an extension of Islamic scholarship. This does not only apply to storytelling with a moral, it also applies to more mainstream journalism.

That is why, over my relatively long career in the media — spanning more than 30 years — I have developed two media modules or educational courses based fairly and squarely on Islamic scriptures and literature. Unfortunately, I have not had a chance to actually teach them yet!

Your book includes insights and observations on tensions within Pashtoon culture and observations on the history and politics of Afghanistan, India and Pakistan. How do you see these dynamics between the three societies unfolding in the near future?

I will try to answer it as honestly and also as tactfully and concisely as possible. In the old days, the road of Islamic learning led from Afghanistan and the Pashtoon parts to Deoband in India.

In my opinion, that was a good thing. Of course, substitutes for Deoband were established in Pakistan but I feel those institutions became more politicised largely due to the nature of the environment in which they were operating. I cannot say how things will unfold but what I would like to see is there being a climate of peace and an atmosphere of mutual trust between India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

What are your thoughts on the growing British Muslim population?

It is very complex and after just over two years of trying to navigate the choppy waters of British Islam, I am not having much success. I still feel much more at home in the familiar fields of Asian—Ajami—Islam in Central and Southern Asia as they share one common Islamic — predominantly Hanafi — culture. British Islam, on the other hand, is a melting pot of different Islamic cultures.

In time, Insha’Allah (God willing) one type of homogenous British Islamic culture will emerge. There may be pockets of it even now. It will take time for that to spread and cover the length and breadth of the British Isles. I believe this will be a good thing. It will enable common terms of references to emerge. If there was a common Islamic culture, a unified, unchallengeable position — a consensus — would emerge on such matters.

Are you working on any new writing projects?

Yes, a tafseer — commentary of the Holy Quran — written in an up-to-date style of English that addresses contemporary questions. People depend on the old Arabic and Urdu tafseers. These were written for a different time and place. There seems to be a need for a solid, scholarly tafseer that young people born and brought up in the West can read and feel is talking to them.

I am working on such a unique tafseer that utilises all the disciplines I have immersed myself in — Islamic scholarship, media work, storytelling, dialogue writing and simulates the relationship between a teacher and a student.

This relationship is so important in the communication of Islamic scholarship. I will be putting some previews on my YouTube channel, Insha’Allah. I hope it will not be long before I am able to leave this tafseer to my own children and to the next generation in general. May Allah accept it as a charity in perpetuity from me.

Dr Sadek Hamid is an academic who has written widely about British Muslims. He is the author of Sufis, Salafis and Islamists: The Contested Ground of British Islamic Activism.

Follow him on Twitter: @SadekHamid

![Minnesota Tim Walz is working to court Muslim voters. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2169747529.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=b63Wif2V)