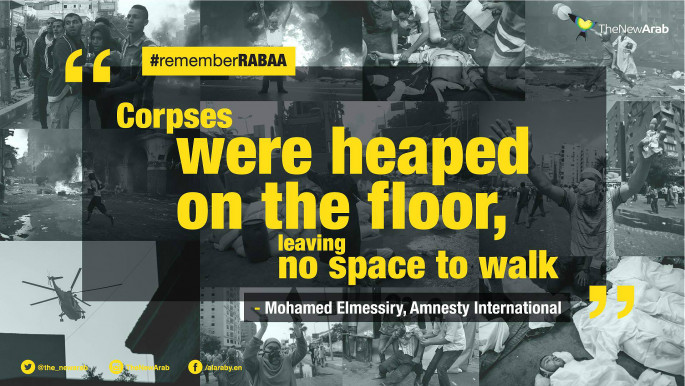

Rabaa Square and the long search for justice

Thousands had arranged sit-in protests against the July 3 military coup and show their support for deposed President Mohamed Morsi. Thousands were killed that day when security forces brutally suppressed the protests.

One of those was Omar Mohammed Ali – also known as Kano – an amateur rapper who was on his way to university to rehearse for a concert.

"The bodies are already buried," a guard told a relative who went looking for him.

Omar was a member of the liberal Ghad al-Thawra Party, and he and his sister Mariam lost each as they passed the packed square.

When the massacre was over, Mariam moved between the injured and dead trying to find her brother. There was still hope when some said they had seen him in custody.

Omar's family embarked on a fruitless journey to find him. They searched hospitals and morgues and even DNA tested scorched human remains.

They went to cemeteries and prisons – military and civilian – but everywhere they met with the intransigence of the army and police. Even now they still refuse to confirm or deny whether or not they ever detained Omar.

More missing

Hundreds more Egyptians have disappeared in the regime's crackdown against the now outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

But the bloodiest day by far took place on August 14 in Cairo. A blaze started at Rabaa Square on the evening and destroyed the main stage of the protest, a field hospital, mosque and the first floor of the Rabaa hospital, which was razed to the ground by army bulldozers. There were areas that the wounded and dead had been brought.

|

Some corpses have been identified by DNA tests, but others were too ravaged by the fire to name.

Most of the bodies of those killed during the dispersal of the Rabaa sit-in were severely charred or disfigured, according to medical experts.

For the rest of the disappeared, the families suspect they were either detained and remain alive in jail, or were killed and buried in secret. There are rumours of a mass grave at a police camp on the Cairo-Suez road.

Families still persevere in the hope of identifying their loved ones. Some have been lucky. It took the family of Mustafa al-Meadaway two months before DNA tests identified his body. Mustafa's brother Muhammad had followed countless leads, which often went down dead-ends before they came to the truth.

His brother was a computer engineer who had been killed at Rabaa, and rushed immediately to the square to find him.

He got to the perimeter of the square at 9pm and after several attempts to scale the fence managed to enter the back entrance of the Rabaa Mosque. There he saw more than 100 partially or fully burnt bodies, too disfigured to identify.

Muhammad continued on to al-Iman Mosque, where dozens of bodies had been transferred. From there he went to hospitals which were expected to receive the injured and the dead.

He returned again to the Rabaa Mosque the following morning, but the place had almost completely burned down, and found no trace of the body.

Mass graves

Mohammed was told by a close friend that police and army bulldozers moved dozens of bodies out of Cairo to be buried at the "Kilometre 21" camp during the night, a police barracks along the Cairo-Suez road.

A friend of Muhammad's went there but was stopped by security who warned him never to come back.

"The bodies are already buried," the guards told him.

|

|

On October 19, Mustafa's disfigured corpse was finally identified by a DNA test among the charred remains found at Rabaa.

Hassan al-Banna Eid was an engineering student whose family were also driven on a fruitless two-month search. It eventually circled back to the charred remains at Rabaa and DNA confirmation.

Omar's family embarked on what would prove a fruitless journey to find any trace of him

But for relatives of those still missing, there has been no closure. The Khedr family launched a campaign to find their missing son Muhammad, but again no remains have been identified.

Even finding loved ones can be a dangerous quest for these families. As a result of the campaign, Muhammad's father and brother were arrested by authorities and charged with membership of the Muslim Brotherhood, protesting without permit and incitement to violence.

The rumours of a mass grave close to the Cairo-Suez road continue. The suggestion was first aired publicly in January by al-Jazeera host Ahmad Mansour, who initially attributed the information to the London-based media website, Middle East Monitor. The website later clarified that it was not the source, but added in a tweet "that doesn't negate the occurrence of the crime".

On March 5, the London-based Human Rights Monitor – a single-issue watchdog focused exclusively on Egypt's military coup – said in a report that that a mass grave for victims of Rabaa was located inside a police camp on the Cairo-Suez road.

The existence of a mass grave is disputed by the government but if confirmed it would lend weight to the growing number of accusations that the Egyptian regime engaged in crimes against humanity.

Salma Ashraf, a researcher with HRM, said the organisation had documented 140 cases of missing persons, statistics that are almost exactly mirrored by the Wiki Thawra website, which was set up by the Egyptian Centre for Economic and Social Rights.

Out of a total count of 924 protesters missing – according to Wiki Thawra – 693 had been identified and their bodies located, 30 unidentified bodies were buried in state-owned cemeteries, and 14 completely charred bodies were eventually identified through DNA testing. The rest remain unaccounted for.

#RememberRabaa: Watch our special video coverage here and join the conversation by tweeting us @The_NewArab: