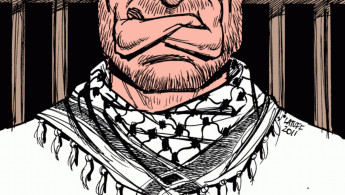

Prison politics behind Palestinian hunger strikes: Sami's story

Organised behind the confines of prison walls, it isn’t well understood and can be difficult to examine.

One of the important tools Palestinian prisoners use within this movement is hunger strikes.

However the nature of these strikes have altered drastically with the changing political sphere within Palestine, moving from collective action to improve conditions in Palestinian prisons, to individual, lengthy strikes to gain freedom.

In the first of a series of interviews with former and current prisoners involved in hunger strikes since the late 70's, we speak to Sami K*, imprisoned for the last 11 years in southern Israel's Negev prison, about the politics behind prison organisation and hunger strikes.

Striking during the intifada

"The hunger strike was in response to the repressive measures and humiliation practised against Palestinian detainees, like strip searches, at the hands of jailers in order to contain the intifada," Sami begins, speaking about the strike of August 2004 where 4,000 prisoners joined the fast.

"[It was] a message to the people outside about what awaits them inside prisons and also an attempt to break the spirit of resistance."

However, during the strike, there was an issue between the hunger strike 'steering committee' and the prisoners who carried out the longest sentences.

The latter negotiated with the Israeli prison administration, who said that they would fulfil demands.

Confusion emerged and the hunger strike ended in some prisons, but continued in others.

|

The strike was in response to the repressive measures and humiliation practised against Palestinian detainees like strip searches at the hands of jailers in order to contain the intifada |  |

"The leadership of the prisoners movement became decentralised where every prison has its own leadership, and even in some locations, a separate leadership for each section of the very prison," he said.

"The isolation of the steering committee in addition to the differences that existed between Fatah and Hamas led to the failure of the 2004 hunger strike."

Following this, sections of the prison were divided by region.

For example, "the people from Nablus area divided into different sections, a section to the people of the city and one to the people from Balata refugee camp and so forth," Sami said.

"Intelligence officers inside prisons took advantage of these divisions and worked to deepen the geographic segregation.

"Decisions that are made within these isolated geographical groups reflect the specific interests of prisoners in this section and do not reflect the interest of all prisoners," he said.

"Hamas has a clear organisational form and a central organisation and is linked to the outside. Any decision taken by the movement represent the prisoners since they are officially taking part of the decision making process."

This reflects a core difference between Hamas and Fatah’s attitude towards action inside prisons, where Hamas' priority appears to be freeing their prisoners, rather viewing the prison itself as a site of resistance.

"On the other hand there is a lack of representation of prisoners in the official bodies of Fatah," said Sami, who is affiliated with the movement, and feels that the particular outlook of Fatah detainees entering prisoners is "an important issue that many avoid to deal with."

Fatah in Prison

|

|

|||||

"They generally did not have a link to organisation institution in Fatah.

"After entering the prison, the emotional aspect which caused them to get engaged in the resistance disappeared and they became interested just in everyday life… not the organisational interests and public interest or visions of the prisoners as a community."

This development also reflects Israel's widening of prisoner demographics.

As many others have testified, at the beginning of the occupation many of the prisoners were those that were involved in organised political parties.

As the second intifada gained traction, the net was widened to include young people whose political activity might be confined to throwing stones, and were not officially members of any faction.

Many of these young people chose to reside Fatah sections in prisons, due to social and practical reasons, such as being with friends, and hope for more aid from the PA.

"This is a major problem within Fatah in the prisons, but this does not negate the existence of a large cadre of Fatah in the prisons who had an important role in the student movement and the youth organisations… before they were arrested," he said.

"But mostly they have no power to bring about significant changes in the organisation and reality of the prisoners," Sami concluded.

Shalit deal and tensions with Hamas

|

|||||

"The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine [a leftist faction] started a hunger strike before the Shalit deal,” Sami said.

"The demands of the hunger strike was to bring the situation inside the prisons to the period before the Shalit law was approved."

The 'Shalit law', implemented after the soldier’s capture, was designed to further worsen conditions in prisons; it deprived prisoners of the right to university education, to receive gifts from families during visits, and prohibited family visits altogether for those from Gaza.

"During this strike, the Shalit deal was reached and the Hamas leadership decided to suspend the strike after the arrival of the news of Shalit deal to the prisons. The PFLP refused to end the strike. The result of this strike was ending Ahmed Saadat’s isolation," said Sami.

Sadaat is the secretary general of PFLP and has been imprisoned since 2002.

He recently launched another hunger strike and campaign of disobedience which was consequently cancelled.

"After the Shalit deal an internal problem within Hamas started to escalate in the prisons… about the criteria that was implemented to determine the names of the prisoners to be released according to the deal," Sami said.

Meanwhile, Hamas decided to enter the hunger strike to demand family visits to the prisoners from Gaza.

"There was a dialogue between Fatah and Hamas on the strike, I was present during the dialogue at that time which took place in Ramon prison," Sami said.

"We have been communicating with Hamas, to form a steering committee for the hunger strike, the committee should be formed based on the number of prisoners each faction have… Hamas refused, and insisted to have four representatives on the Committee and to be in command of the strike.

"Fatah reached the conclusion that Hamas wanted to enter the hunger strike alone. Prisoners in Eshel and Ashkelon withdrew from the strike.

"The strike lasted for 29 days and resulted in bringing out the prisoners from solitary confinement and approval to family visit for prisoners from the Gaza Strip.

"We call this strike the 'co-opting strike' because it was made to contain the tension within Hamas after the Shalit deal," Sami said, explaining that the original strike was planned to restore prisoner’s rights to what they had been before a crackdown on prisoners in 2000.

"Hamas wants to exploit the hunger strike politically. After that and through other dialogues Hamas announced its rejection to have Fatah represented in the strike."

Sami is not the only one to criticise these strikes; a Facebook group called Don't Stab the Hunger Strikers in the Back also criticised a premature deal as the strikes were apprently gaining momentum, as did blog posts at the time.

"The internal situation currently is heavily influenced by differences prevailing between Fatah and Hamas," Sami concluded.

The development of the lone hunger striker

|

|||||

The year of 2011 saw the growth of individual hunger strikes, where prisoners would strike alone for a far longer period of time that the previous collective strikes.

The most well-known of these strikers is probably Khader Adnan, who went on strike in December 2011 following his imprisonment under administrative detention.

However, Sami said there was some precedent to the growth of the individual hunger striker.

"We had some cases like people who were in solitary confinement who did go in hunger strike... usually [these] people receive support of the rest of the prisoners," he said.

"However some individual hunger strikes started when prisoners saw that it was a time for an action against the prison administration but the leadership of the prison decided otherwise… these people announced that they are going to start a hunger strike and thus they demand to be moved to a special section."

Although these strikes attracted much international solidarity, and few criticise the bravery and sacrifices of strikers like Khader Adnan, within the prisoner community, there are mixed feelings towards the strategic value of individuals striking for longer and longer periods of time.

"We don't encourage individual actions in the prisoners movement, in any organised body the decision shouldn't be taken without the consensus of the rest of the members of this structure, individual decisions causes harm to whole structure and to the collective interest of the prisoners," Sami said.

"Despite all of that, when the administrative detainees took this step that started with Khader Adnan the prisoners movement supported them."

Like others, Sami feels that these strikes have lessoned the impact of the tool.

"The individual hunger strikes drained the hunger strike tool," he said.

"Before this wave of hunger strikes the reaction to hunger strike was huge in Israel, the prison administration used to seek negotiations with prisoners after a week or 10 days... think about it thousands of prisoners are in hunger strike, this used to cause a dilemma [for Israel].

"But since the individual hunger strikes started the threshold raised, so it's hard to reach anything now in a collective hunger strike, you cannot expect from thousands of prisoners to be in hunger strike for 50 or 60 days, the individual hunger strikes deprived this strategic tool (weapon) of its effectiveness."

Sami also feels that consequently the Palestinian public has become somewhat desensitised to these strikes.

"Prisoners and the street in Palestine don't react the same way to hunger strikes, we are hearing everyday now about new hunger strikes that last for 50 days or even a 100 days, the credibility of the hunger strike in the street is lost.

"In the past when prisoners went on a hunger strike for ten days, the streets used to burn and solidarity actions were organised everywhere," he said.

Solidarity actions towards hunger strikers in Palestine include small sit-ins and protests outside the Red Crescent offices.

"We cannot just accuse the Palestinian people of not caring, this is completely unfair, the Palestinian people still have the capacity to raise any moment," Sami said.

"These hunger strikes drained the solidarity of people outside the prisons to the level that we lost the credibility in the street… some people even started to question it, 'a person went in a hunger strike for 100 day, how could he survive?'"

"Only one of those [Samir Isawee] who were in a long hunger strikes admitted that he took like vitamins during the hunger strike."

Khader Adnan told The New Arab that he also said that he had accepted vitamins, but refused other substances.

"I have been in prison for 13 years now, I saw the hunger strike as my last weapon that I can use," Sami said.

"It's my suicidal tool, the last thing I used when I tried everything else…"

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News