Yemen's 'great game' is not black and white

Yemen's post-revolution transitional process is unravelling and leaving behind complex and intertwining conflicts and enmities. Any tempation to apply binary interpretations - north/south, Sunni/Shia - risks pushing the country to the abyss and creating a second Libya senario.

But how can such a mess be explained?

First, the Houthis. They are the bete noir of the Saudi alliance after taking over Sanaa and pursuing the president, Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi to Aden after he fled house arrest.

The Houthis, a politico-religious movement deriving from the Zaydi branch of Shia Islam, was a marginal group which built popularity and power over the years, and especially since the 2011 revolution - culminating in an effective, if undeclared, coup earlier this year.

This takeover, however, would not have been possible without a circumstantial alliance between Houthis and former president Ali Abdullah Saleh who stepped down in 2011 following protests against him.

It is an alliance that continued to benefit from the allegiance of a significant part of the security apparatus. It was an alliance between former enemies who had fought each other in the Saada war between 2004 and 2010 and that allowed both to take vengeance on their common opponent, the Islah party - the Yemeni branch of the Muslim Brotherhood that is allied with Hadi.

|

|

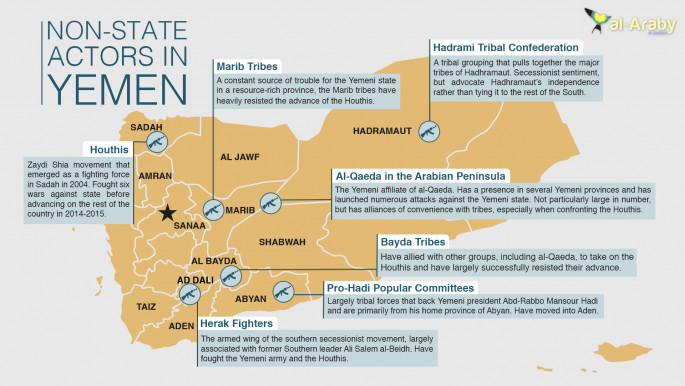

| Non state actors in Yemen. Click here to expand. |

The Houthis earlier this year apparently applied the coup de grace by forcing Hadi's resignation. However, the president escaped house arrest and set up in the southern port city of Aden.

Hadi's re-stated his constitutional legitimacy from his new location, and announced the temporary transfer of the capital to Aden. But this move has had the effect of dragging the country further into division. Although he hails from Abyan, a governorate neighbouring Aden, Hadi's political base in his city and in the south of Yemen in general has been weak.

The former south Yemen population has been largely in favour of secession. It also remembers Hadi having led, as minister of defence, a military offensive against Aden in 1994. Hadi was up against one of the main secessionist leaders, Ali Salim al-Bidh, following a dark and murderous southern purge in 1986.

Hadi is however the champion of the international community. The UN Security Council supports Hadi but does not take into account that his flight to Aden has further split the country. The UN and major world powers have sided with his camp, while calling for negotiations between all parties.

Binary polarisation

Aden had remained for a long time, since 2011, far from the competition between elites in Sanaa where Houthis, the Muslim Brotherhood, Saleh's partisans and supporters of Hadi were all involved.

The southern population which largely supported the secessionist movement no longer felt concerned with the affairs of the north and demanded independence.

But Hadi's move to the city turned the tables drastically and violence began to sweep through Aden. The airport situated in the downtown area witnessed violent clashes in mid-March between forces supporting Hadi and others opposing him. Jetsd sent by Sanaa, likely piloted by officials loyal to Saleh and allied with the Houthis, bombed Hadi's temporary palace.

This reshuffling of cards has also framed a complex conflict in simplistic interpretation - historical, geographical and confessional: The Houthis belonging to Shia Zaydism, the recurring accusations of their Iranian support and their rivalry with the Muslim Brotherhood definitely gave the conflict a religious aspect.

| Aden had remained far from the competition between in Sanaa between Houthis, the Brotherhood, Saleh's partisans and supporters of Hadi. |

The north embodies the Zaydi identity and its followers engaged in a wave of rejection of Sunnis dominant in Yemen in general, but a minority around Sanaa.

The assassination of the intellectual Houthi, Abdel Karim al-Khaywani, on 18 March 2015 and, two days later, the attack against the two Zaydi mosques in Sanaa, killing more than 150 people, reinforced this sectarian polarisation that seems to be on the rise.

The Islamic State group that was until that point inactive in Yemen claimed responsibility for the attacks, thus reflecting devastating dynamics. For their part, the Houthis who were advancing on Sunni areas in Yemen, particularly Taiz and later Aden, expressed deep resentment.

On the other side, to the south, the population is exclusively Sunni. Hadi can therefore use this as a counter to the Houthi rebellion and Shia Islam, as well as the south's rejection of the north.

Nevertheless, the main impediment to the advancement of the Houthis is al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which is allied with the tribes of the border areas between north and south in al-Baida, al-Dhala or the Yafea.

In this context, anti-Houthism, turned anti-Shiism, constitutes a strong and firm bloc. However, it does not erase the internal divisions within each camp.

Divided camps

Hadi's moves have ultimately led to consolidating the idea of political separation that the southerners had called for since years. The Houthi controlled capital and its surroundings are disconnected from the rest of the country, even worse isolated from the world, except for Iran.

Nevertheless, it is not certain that this division would realistically turn the southern secessionists' expectations into reality. In fact, it immediately highlights the internal divisions in the southern movement itself.

The Houthis have stepped into the breach by announcing having offered Bidh, the former president of south Yemen and secessionist leader, a diplomatic passport that would allow him to return to the country after more than two decades in exile.

The positive alliance between Hadi and the jihadi groups in their common fight against the Houthis has put Hadi in an awkward situation in respect of his support among world powers.

| Hadi's moves have ultimately led to consolidating the idea of political separation that the southerners had called for since years. |

Regional calculations also had a major role to play in the south. The historic rivalries between tribes in Abyan, al-Dhala and Lahj, north of Adenm have divided the south. Hadhramaut, the oriental governorate of the south, seems to be relying on its trade ties with the Gulf to take a different path. Its inhabitants have been little concerned with the turn of events between Sanaa and Aden.

Houthi divisions

The Houthi camp, firmly united by a desire for revenge against Sunni fighters and their allies, is not itself free from internal divisions.

The military success of its militia can only be understood in light of its integration of whole sections of security forces that remained loyal to the former president Saleh.

The alliance between Saleh - a Zaidi himself - and the Houthis is certainly functional but it is hardly sustainable between two former enemies who, in addition to their historical enmity, are adopting different strategies.

The chaos is playing to Saleh's benefit. From his home in Sanaa, he gives orders.

The prevailing divisions, which are draining citizens, could impose the resurgence of Saleh's connections through his son Ahmed Ali, former leader of the Republican Guard.

In his capacity as ambassador of Yemen to Abu Dhabi which he has been handling since 2012, he is able to establish basic connections with influential regional players, such as the UAE and also Saudi Arabia, and thus appear as a point reference to fall back on.

For their part, Houthis are clearly antagonistic towards the Saudis who they have recently threatened. They want to put their hand on natural resources, particularly in the oil region of Marib, where they face resistance from tribes (not necessarily Sunni ones).

The Houthi strategy is mainly reflected in a frontal fight against the Sunni militants close to al-Qaeda or currently affiliated with IS.

The problem lies in the fact that each time Houthis advance, Sunni solidarity is reinforced, as a reaction, according to a perverse and self-fulfilling logic.

The apparent willingness of Houthis to learn from the experience of the Lebanese Hizballah party and the Iranian state would have worked better if they had limited themselves to a certain territorial base and to an alliance with other political forces.

The latter could have provided a shielding veneer for Houthis, but at the same time, an interface before the international community. However, recent events have decided otherwise - undoubtedly taking the situation from bad to worse.

This is an edited translation of an article from our French partner site, orientxxi.