Yassmin's Corner: Re-orienting the lens of travel through the eyes of a Muslim woman

Growing up, my father was obsessed with Ibn Battuta. "Our very own Marco Polo," he would say to my brother and I, as we wandered aimlessly down the brightly lit aisles of our local grocery store during the weekly family shop. We were never quite taken by Baba’s admiration of this mythical figure, one we knew so little about. There were tens of books in the local library about the famed Italian merchant and explorer - even a game named after him that we played in and around discounted piles of tomatos, oranges and potatoes. But this, ‘Ibn Battuta’ fella? Who on earth was he?

Frustrated by our lack of interest, my father tried another tack. "Okay, some homework for you," he said. "Paid, as well!" Now, our interest was piqued. "If you write a short report on Ibn Battuta and his travels, I will give you $100."

"And what a shame, for I then grew up somehow absorbing the idea that travel and exploration was something reserved for white men, for the coloniser, for a heart of conquering and darkness, rather than a tradition that I belonged to. It was not going to be a story of curiosity and joy in which I would star as the protagonist, rather than simply be referenced in the background."

$100 in the 90’s, for an 8 year old, was like winning the lottery. But alas, in our pre-broadband existence, a lack of available information made winning this particular jackpot all but impossible. Even the entry under ‘Battuta, Ibn,’ on our CD copy of Encarta 95 was sparse on detail. And what a shame, for I then grew up somehow absorbing the idea that travel and exploration was something reserved for white men, for the coloniser, for a heart of conquering and darkness, rather than a tradition that I belonged to. It was not going to be a story of curiosity and joy in which I would star as the protagonist, rather than simply be referenced in the background.

Ibn Battuta was born in the early 14th century, in today’s Morocco. From a family of Qadis, Islamic judges, his travels began after he first journeyed to Mecca for Hajj, at the age of 21. It is said that from then, his love of travel was born, and he apparently set himself a rule "never to travel any road twice."

Batutta travelled more than any other explorers in pre-modern history. He beat famed Chinese Muslim Mariner Zheng He’s record by about 50,000km and surpassed my childhood favourite Marco Polo by 24,000km. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his travels were neither for economic nor scientific reasons but for the joy of exploration, and ultimately his legacy lived on in an incredibly rich account entitled Rihla. This was the book my father had tried so valiantly to get us to read, but an English translation was difficult to come by in our local Brisbane bookshop.

But Battuta is just one man, and one man, no matter how well travelled, does not a destroyed myth make. That is to say, it would take more than just learning about the North African explorer to undo the internalised ideas I had about who could travel and what value it would possibly have for a multiple migrant like me.

It is at this point that I should mention these internalised ideas did not come from my immediate family, at all. In fact, my father loved to explore, and we often would- at least, as much as we could with the limited budget of a first generation migrant family. Curiosity - of the scientific and cultural nature - was always encouraged in our household; from how to fix a leaking tap, to watching German TV shows, to learning a different language in order to hear the news 'from a different perspective’. And yet still, somehow, when I graduated from university and my friends went backpacking around Latin America and Asia, I travelled back to Sudan to live with my grandmother. Why waste time exploring other people’s cultures when I didn’t even really know my own, I thought. Why learn a new language when I had yet to master my mother tongue? Why intrude, gawk, trample, lark through another’s home when I have spent so much of my life resisting and repairing the damage caused by those who thought the earth was theirs for the taking?

I had yet to understand there are many multiple ways of moving through and across our world, that this did not have to be a zero sum game. This slow shift crystallised when I came across a twitter thread by @milkwrath earlier this year.

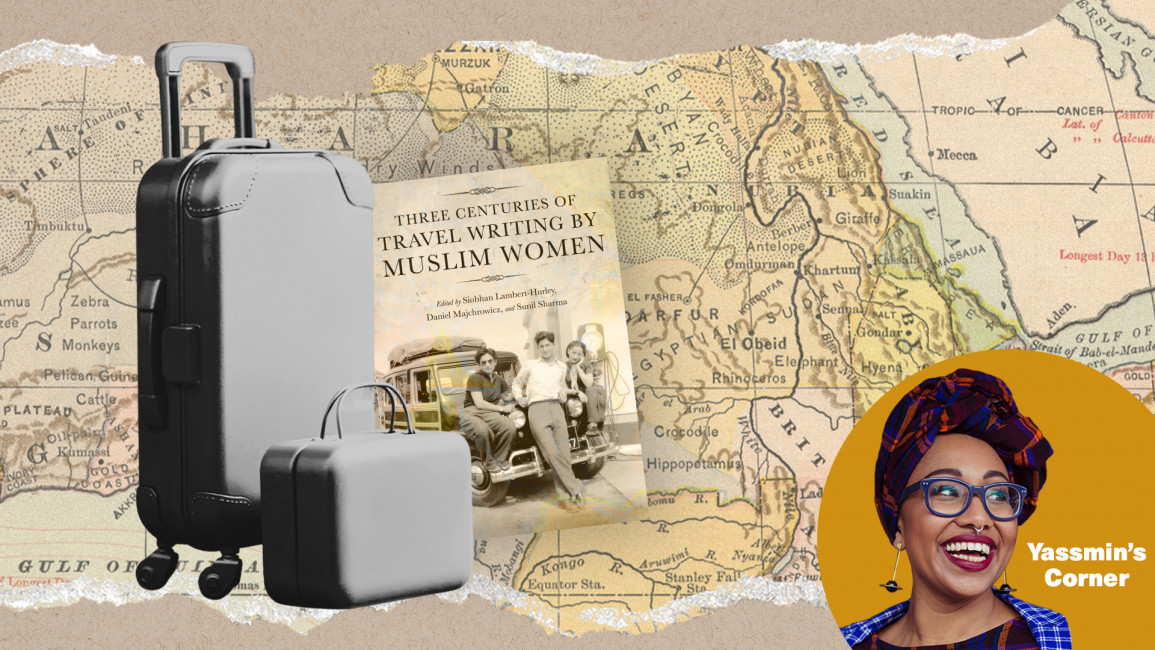

10 books that ‘flip the myth of travelling as a white colonial pastime’, they shared, and the good people of twitter supplemented the initial list with plenty more. One was a collection of 45 Muslim women traveller’s writings from the 17th - 20th centuries, another, A Muslim Woman From Colonial Bombay to Edwardian Britain a translation of Atiya Fyzee’s diaries as she explored Britain at the turn of the 20th century. Beyond the Muslim experience, there were books like Inscribed Landscapes, an anthology of writing by Chinese travellers through their own country from the 1st to the 19th century, and Contemporary Travel Writing of Latin America, focused on Latin writers from the late 20th century narrating experiences in Patagonia, the Andes, Mexico and the Mexico-US border.

"By beginning to explore the writers and travellers from these books, I was able to re-orient the lens through which I approached the idea of travel. "

This was decolonising in a way I hadn’t experienced before, not focused on an education syllabus or a distant academic exercise, but something much closer to home. It was shifting the perspective from which I understood who travelled, and for what purpose. Even the idea that I had to ‘allow’ myself to enjoy it was something these books and diaries refuted. Who was I seeking permission from? Why couldn’t I be the observer? And perhaps a more contemporary question I asked myself, was how would I practice said observation in a way that didn’t do to others what was done to us?

By beginning to explore the writers and travellers from these books, I was able to re-orient the lens through which I approached the idea of travel. Of course, a lens is one thing, and the reality of borders and visas is another. However, by looking back to those past explorers, I am now able to look forwards with fresh excitement and anticipation, to a world not mine for the taking, but certainly mine to explore.

Yassmin Abdel-Magied is a Sudanese-Australian author and social justice advocate. She is a regular columnist for The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @yassmin_a

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.