The world doesn’t care about the Myanmar military’s crimes

It took until March of this year for the US to designate the mass killing and cleansing of Rohingya Muslims by the military junta in Myanmar a genocide.

In just over three months, from October 2016 to January 2017, at least 700,000 Rohingya people were cleansed from their home in the West of the country, fleeing to neighbouring Bangladesh, where half-a-million people live miserably precarious lives crammed into one of the largest refugee camp, something that ought to be thought of as a stain upon the earth.

Instead, both the crime carried out by the military junta in Myanmar, which is infused with a virulently Islamophobic, sectarian and racist Buddhist nationalist ideology, and its consequences, have been absorbed into global normalcy.

Among the liberal democratic West, despite a brief swell of care, including television charity appeals and celebrity interventions, the plight of the Rohingya and the crimes of the Burmese military have been forgotten.

''Perhaps the fact that Western states have used ‘war on terror’ narratives to justify everything from supporting tyrannies to implementing their own brutal anti-refugee policies, is the reason that they are unable or unwilling to undermine similar activities by other nations.''

Other than a few weak sanctions, it has largely been business as usual between the world and Myanmar’s China-backed military junta, despite it carrying out genocide against a minority group, seizing absolute power in a coup d'état last year and crushing all dissent.

It's not as if the crimes in Myanmar are confined to the past; in fact, the opposite is true. Not only do the Rohingya continue to suffer, but the military junta continues to carry out crimes with genocidal intent.

Though the world is currently rightfully exercised by the crimes of Russia in East Ukraine, the atrocities in the east of Myanmar have received very little coverage in mainstream media.

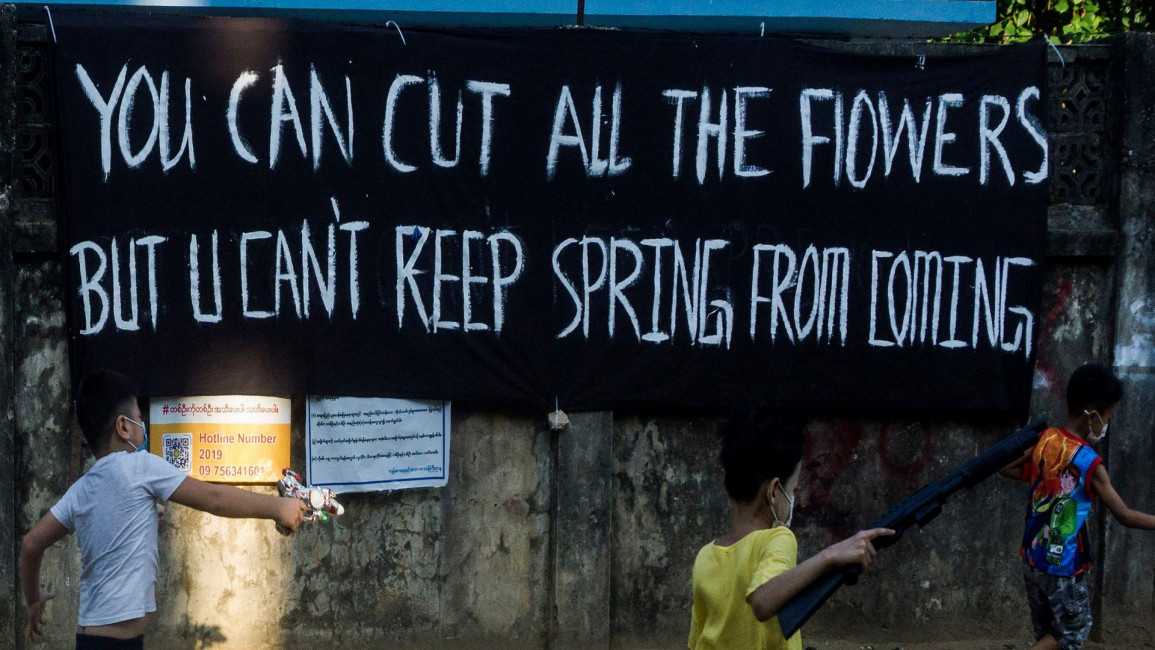

The violence first erupted in the states of Kayah and Kayin, which are populated by the Karenni and Karen ethnic minorities respectively, after they rose in defiance of the coup and the decades-old, centralised chauvinism of successive majoritarian rulers in Myanmar.

So far the violence, as documented by Amnesty International among other NGOs, is ominously like the beginnings of the Rohingya genocide in the West of the country.

The military have carried out a plethora of atrocities in the two eastern states, including the mass killing and collective punishment of thousands of Karen and Karenni civilians by way of aerial and ground assaults by the military, leading to the displacement and cleansing of at least 150,000 people.

As well as this, there has been the arbitrary detention of thousands, the widespread use of torture, and the weaponization of sexual assault.

All of this is justified by the Myanmar regime by painting the legitimate struggle of movements in Kayah and Kayin for greater autonomy and civil rights as ‘terrorist activity’.

Indeed, the particular hatred of Islam and Muslims within the ruling ideology of the Myanmar regime is peddled under the guise of the ‘war on terror’.

However, as movements around the world have already pointed out, the state’s targeting of Muslims is usually a starting point of the wider repression to follow. Attacks on the non-Muslim Karenni and Karen peoples demonstrated that in reality, no one is safe.

Myanmar’s justification for its atrocities in Kayah and Karin, as well as Russia’s justifications for its attack on Ukraine, illustrate that the ‘war on terror’ narrative can be adapted and expanded to justify militarised brutality and state terror against any minority group.

As soon as the word ‘terror’ is used by these forces, domestic audiences are fooled into believing their government is doing whatever it takes to destroy an existential threat to their country. Perhaps the fact that Western states have used ‘war on terror’ narratives to justify everything from supporting tyrannies to implementing their own brutal anti-refugee policies, is the reason that they are unable or unwilling to undermine similar activities by other nations.

But, more than anything, it seems to be a case of sheer disinterest.

For much of the Western world, Myanmar belongs to the savage lands of the ‘third world’, where genocide is normal and simply part of the realities of world order. This brand of realism, which has infused successive US presidencies and reigns supreme in the foreign policy of many European countries, is one of the reasons why genocide, as well as other crimes against humanity, has re-emerged on the world stage with a vengeance.

One could easily retroactively look at this disinterest and contrast the way the West reacted to the Rohingya genocide, with how it has reacted to Russia invading a European country and unpack the racialised power relations behind it. But this is occurring in real time. The lack of action against the Myanmar regime will only embolden it to increase the scale and ferocity of its attacks.

If even relatively mild action had been taken against the Myanmar regime, the country might not be sitting on the precipice of yet another genocide.

Yet western and global businesses continue to trade with their Burmese counterparts, including ventures operated by and to the benefit of the kleptocratic Burmese military

There is a perfect storm gathering in Myanmar: as the country moves into its notoriously devastating monsoon season, combined with the upheavals of war, much needed food and medical aid will be almost impossible to deliver to the millions of people who need it most.This could lead to unprecedented mass starvation in Kayah and Kayin, something that the regime would embrace like imperialist monsters of old, deliberately starving ethnic and religious minority populations deemed to be troublesome and inferior to the majority.

If one looks at Myanmar holistically, it almost defies belief: the world watched as the Rohingya were subject to genocide, despite the warning signs being there for years before, and now the very same thing is happening in Kayin and Kayah. The only difference is that, if anything, the world seems to care even less.

Sam Hamad is a writer and History PhD candidate at the University of Glasgow focusing on totalitarian ideologies.

Join the conversation @The_NewArab.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.