Turkey: Free from costly conflicts with its own minorities

Turkish politics has just experienced a sea change.

For the first time ever, the country's 15 million Kurds will finally be represented in parliament by a national political party, an achievement that has huge implications for the stalled PKK peace process and for Syrian Kurds.

As Turkish novelist Elif Shafak eloquently predicted: "Once seen by Turkish nationalists as a backward subculture, the Kurds are now Turkey's leading progressive force."

The game-changer responsible for this turn of events is a newly formed group of pro-Kurdish and pro-minority rights parties which has come together under the banner of the HDP (People's Democratic Party), widely seen as Turkey's equivalent of Greece's Syriza and Spain's Podemos.

HDP's all or nothing gamble that by banding together they could cross the 10 percent threshold necessary to gain seats has paid off, catapulting them into parliament with 80 seats after winning 13.1 percent of the vote.

Architect of this unprecedented victory is HDP's charismatic leader Selhattin (Saladin) Demirtas, a 42-year old human rights lawyer, who has oratorial skills to rival President Erdogan's and looks that exceed his. He ran his election campaign brilliantly, showing statesmanlike qualities of restraint in the face of media harrassment and violence.

His new party supports Turkey's future membership in the European Union, calls for the PKK (the Kurdish separatists) to disarm, supports gays and same sex marriage and wants Turkey to recognise the Armenian Genocide. The party's aim is to end all discrimination based on race, religion or gender.

As Turkey's only party championing minority rights, the HDP has gained support from Syriac Christians, Kurds and Alevis. Kurds form the country's largest ethnic minority at around 20 percent of the population, and are growing due to their high birth rate.

| HDP has an automatic policy of sharing all top positions with women, seeking to promote gender equality in politics. |

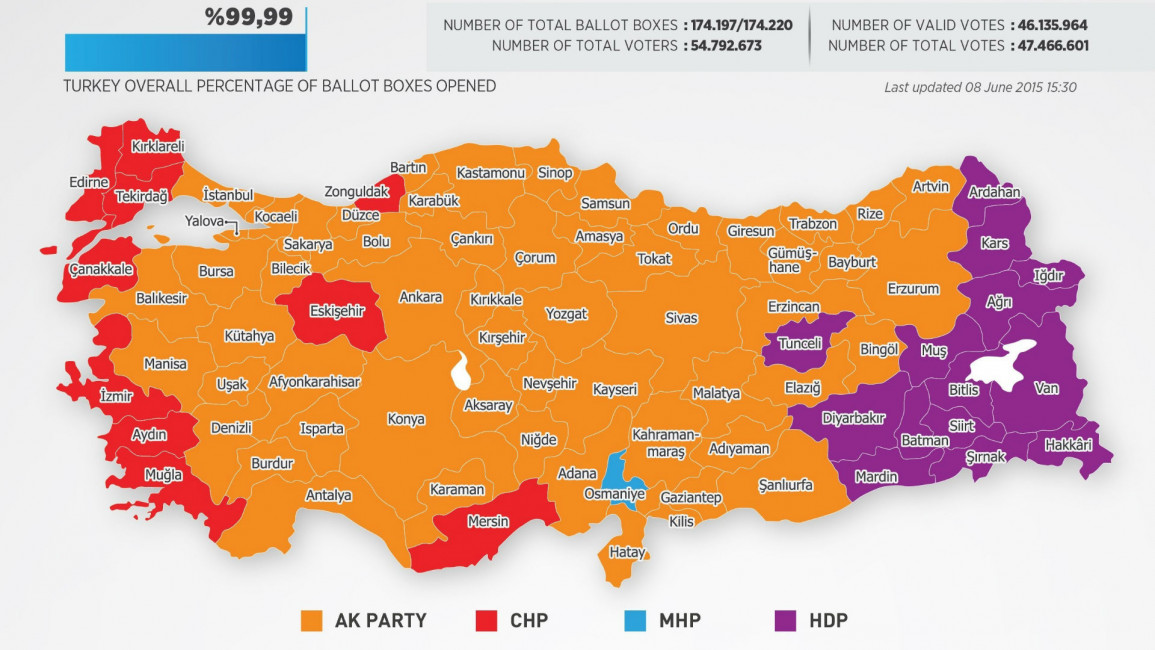

In order to win, Demirtas attracted voters from Erdogan's traditional supporters in the southeast, pulling the AK (Justice and Development) share of the vote down from nearly 50 percent in 2011 to just 41 percent this time. While still the largest single party, AK has therefore lost its majority, thwarting Erdogan's ambition to increase his presidential powers, as the AK party can now only govern in coalition, something they will be hard-pushed to achieve.

Power-sharing is not Erdogan's forte. Hubris has been his undoing, and the tide has turned against him. In his presidential role he was supposed to be apolitical though no one would have guessed it. His electoral rallies were unashamedly pro his own AK party.

His excesses have been well-publicised, from his grandiose 1,100-room White Palace in Ankara to the 'toilet-gate' affair over the alleged golden toilet seats installed at public expense. Corruption allegations are increasing with Turkey now ranking 149 out of 180 in the Corruption Perception Index, even worse than Russia.

Erdogan remains popular in the traditional and religiously conservative Anatolian heartlands. His economic policies over the last decade have brought increased prosperity through vast investment in infrastructure projects like new roads, bridges, airports and high-speed trains to cities like Konya. His encouragement of the headscarf has come as a 'liberation' to many women in Anatolia who say they now feel more comfortable and respected.

But it is in these southeastern regions, where most of Turkey's Kurds are concentrated, that Erdogan's popularity has been challenged in this 7 June election. Turkey's spectacular growth over the last decade has given way to stagnation and high unemployment.

Erdogan's foreign policies have backfired leaving the Kurdish peace process dangling by a thread and his country overrun with two million Syrian refugees. In his recent rallies in the big eastern cities, some women, headscarved or otherwise, quite literally turned their backs on him in symbolic protest.

Turkey has the lowest female employment in the OECD, less than 30 percent, a drop from over 40 percent in the 1980s. Only the HDP has addressed this, through their policy of job-sharing with women in all top posts.

Turnout rose to 83 percent in this election, and that extra 3 percent may well have been thanks to more women coming forward to vote. A sophisticated young Ankara University graduate now working in Mardin told me how impressed she was by the non-discriminatory policies of HDP, with whom she had been working since 2014. "I will be voting for them," she told me. "I think they are the future."

With this sea change Turkey's future is charting unknown waters, leading to an inevitable drop in the Turkish lira and stock market. Once the markets adjust to the change, it is hoped investors, rather than taking fright, come instead to realise the potential of a united Turkey, free at last from its costly conflicts with its own minorities.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of al-Araby al-Jadeed, its editorial board or staff.