Syria and beyond: Manufactured doubt and moral atrophy

Presented with facts about the regime's crimes, Zarif was pugnacious. "No. Those are not the facts", he said. That Assad is a dictator was merely "your impression"; to support Assad was to be "on the right side"; and the problem in Syria was IS, a group that was a "creation of the United States government" and "armed and equipped and financed" by Gulf states.

The man representing a state that supports designated terrorist groups such as Hizballah and whose forces are currently occupying parts of Syria, had advice for the West: "People are making the wrong choices in supporting terrorism", he said; and they must avoid the folly of basing "foreign troops in an Arab territory".

Zarif was bludgeoning irony with alternative facts. But his approach is unexceptional. This disdain for truth has become a defining feature of modern politics. The function of lies is no longer to persuade; it is to challenge the primacy of facts. Relativism has been weaponised by the powerful to eliminate the very possibility of justice.

This doubt is distinct from the kind of legitimate scepticism that might check against unqualified belief. It is ersatz and functional, manufactured to thwart action and allay guilty conscience. Politically immobilising and morally liberating, it sustains political inertia among cynical politicians and the will to disbelieve among jaded publics.

In the 1950s, when the tobacco industry faced the weight of accumulating scientific evidence linking smoking to cancer, it received advice from a PR firm: "Doubt is our product."

|

This disdain for truth has become a defining feature of modern politics |  |

Energy companies eager to impede environmental legislation also found in doubt an ally. For decades unhealthy businesses were able to escape regulation, protected by doubt. Doubt also kept smokers and energy consumers from changing their ways.

In matters of war however the effects of doubt are more lethal and immediate.

Because the regime and its apologists manufactured doubt about its May 2012 massacre of 108 civilians in Houla, no one paid a price and, over the summer, the regime able to get away with several more.

Because doubt was cast over the regime's August 2013 chemical attack on Eastern Ghouta, the regime escaped consequences and escalated the war without relenting on its use of chemical weapons. Because the regime's use of a starvation siege in Yarmouk was shrouded in doubt, it was able to deploy the same tactic in Madaya, Zabadani, Aleppo and Moadamiya.

But if for the regime doubt is a political necessity, for western "anti-imperialists" it bears psychological rewards.

|

|

| "People are making the wrong choices in supporting terrorism" said Zarif on CNN [AFP] |

Because anti-imperialists have shown greater alacrity in protecting Assad from imagined regime change than protecting Syrians from the regime's actual repression, every new atrocity is an indictment of their priorities.

Their response is a willed ignorance. The seemingly absurd attempt to cast doubt on the regime's well-documented chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun thus becomes explicable when one sees it as an attempt to resolve the moral dissonance that might follow if they were to acknowledge that their misplaced priorities have helped a real mass murderer evade accountability.

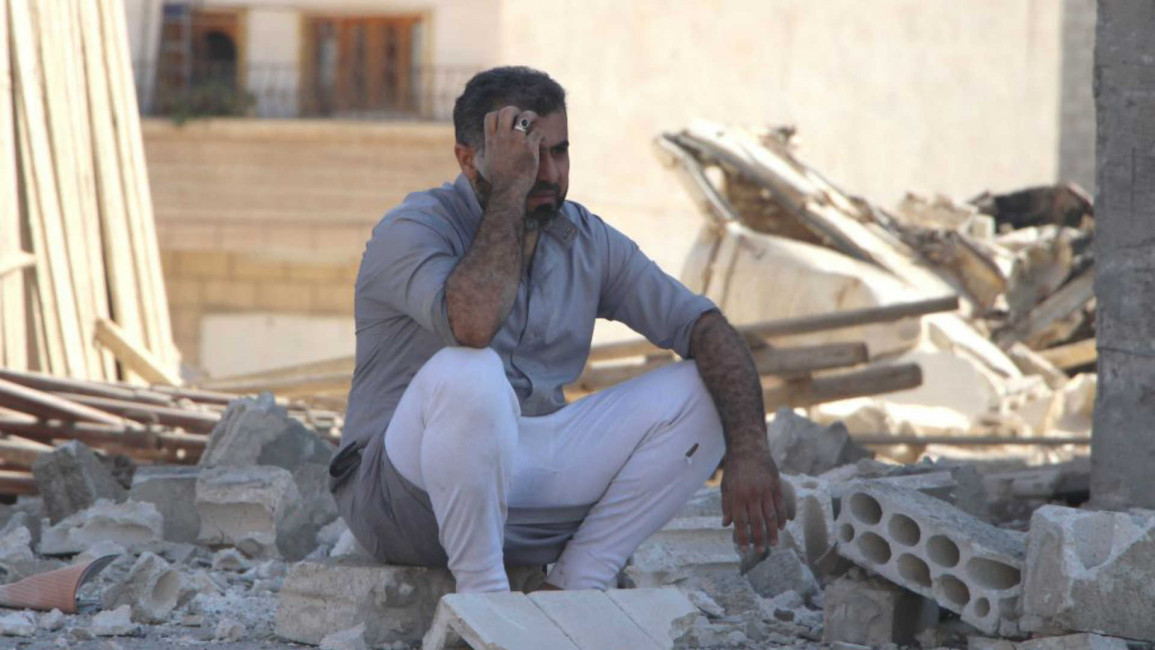

In Syria, since the start of the conflict, there has been a determined effort to obfuscate the regime's well-documented crimes. With doubts manufactured about major atrocities, there is a natural reluctance to assign new blame. In the West, on the political level, commentary about Syria has been reduced to generalised condemnations of violence without recognising the regime as its main author and instigator. A sense of proportion has been lost.

|

Commentary about Syria has been reduced to generalised condemnations of violence without recognising the regime as its main author and instigator |  |

This is what allows bien pensant liberals to condemn "all sides", the cynical to insist there are "no good guys", and the partisans to prefer "the devil we know". Through a false levelling of the moral plane, the apologists for Assad - "realist" or "anti-imperialist" - are able to shift the conversation onto political categories like "containment", "stability" and "security".

Stripped of moral content, the debates thus treat Assad as no worse than his opponents (who are inevitably conflated with IS), except he has the merit of a near monopoly on power (albeit with a little help from Russia, Iran, Hizballah, Iraqi militias, Afghan mercenaries,and Pakistani jihadis).

Facts are what separate judgment from justice.

Philosophical scepticism about the unattainability of truth needn't be allowed to cover for the devaluing of facts. In journalism, as in in law, it is still possible to gather what Hannarh Arendt called "brutally elementary data" whose "indestructibility" is indubitable.

Read more: Chomsky and the Syria revisionists: Regime whitewashing

What is happening in Syria is not a contest of equally valid claims. On one hand we have the denials of the regime, its Russian and Iranian allies, an assortment of ideologues, and a legion of conspiracists; on the other we have the considered judgment of reputable journalists, human rights organisations, UN investigators, arms inspectors, aid organisations, witnesses and the regime's own documents.

|

The function of lies is no longer to persuade; it is to challenge the primacy of facts |  |

If there were any doubts about the regime's actions (excepting those manufactured by the regime and its apologists) the notoriously cautious UN would not have indicted it for "the crimes against humanity of extermination; murder; rape or other forms of sexual violence; torture; imprisonment; enforced disappearance and other inhuman acts".

And now that the world - including the UN - is preparing to rehabilitate the regime, there is no doubt that it is wilfully entrusting Syrians to a regime that by its own reckoning comprises genocidaires, murderers, rapists and torturers.

In her essay "Truth and Politics", Hannah Arendt relates the story of French prime minister Clémenceau having a friendly conversation with a German diplomat about responsibility for the recently concluded First World War.

"What, in your opinion will future historians think of this troublesome and controversial issue?" Clémenceau is asked. He replies: "This I don't know. But I know for certain that they will not say Belgium invaded Germany."

In the post-truth world, such certainties can no longer be taken for granted. Where people would sooner cushion their guilt in uncertainty than face the troubling implications of knowledge, truth becomes an encumbrance.

To arrest this moral atrophy and ensure justice then, it is necessary to restore the primacy of truth. Truth may be unattainable, but falsehoods remain vulnerable to facts. Destroying falsehoods then is our duty to truth and justice.

Muhammad Idrees Ahmad is a Lecturer in Digital Journalism at the University of Stirling.

Follow him on Twitter: @im_PULSE

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff