Saudi Arabia's record-shattering executions are mass murder, and it's getting away with it

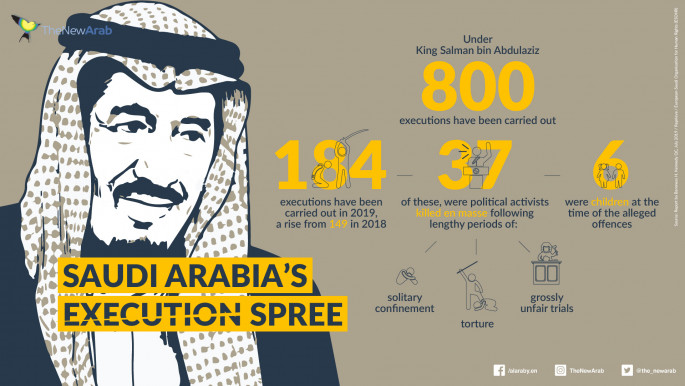

Aside from the latest imprisonments of members of the ruling family last month that further centralised political power in the hands of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), numbers released by Amnesty International today reveal that Saudi Arabia ranks third in the world, following China and Iran, for most executions. Over the course of 2019 alone, Saudi Arabia executed 184 people (including six women and just over 50 percent Saudi nationals) - the largest single number it has recorded in that country, and an increase from a total of 149 executions in 2018.

Further, last Tuesday, UK-based human rights organisation Reprieve and the European-Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR) reported that Saudi Arabia has carried out 800 executions under the rule of King Salman, who came to power in 2015.

This number represents roughly a doubling over the previous five years: Saudi authorities executed 423 people between 2009 and 2014 - still a large number but one which pales in comparison to the current figure. So, what accounts for the increase?

The first mass execution of King Salman's reign, the largest since 1980, took place on 2 January 2016 and involved 47 people, most of whom were accused of being members of al-Qaeda but some of whom were activists from the Shia community, including, most notably, the influential cleric Shaykh Nimr al-Nimr.

|

This pattern is likely to continue if there are no consequences for Saudi Arabia, which is set to host the G20 |  |

The execution was the first of such a high-profile member of the Shia community, and spurred protests in the Shia-majority Eastern Province, as well as in Bahrain and Iran. Although al-Nimr had been arrested in the past and sentenced to death in 2014, there was still shock about his execution. Additionally, the execution of a nonviolent religious figure who urged an opening of political space in Saudi Arabia sent a clear signal that political redlines were changing, particularly for the Saudi Shia community.

|

|

Further, between 2016 and end of 2019, at least 84 Saudi Shia men have been executed or killed in raids by Saudi security forces, according to the ESOHR. In addition to executions of members of the Shia community, raids were also conducted in Awamiya in the Eastern Province in May-June 2017, which led to the government's demolition of ancient homes in the search for alleged terrorists.

As a result, in July of that year, the Saudi Supreme Court pronounced death sentences for 14 of 23 Saudi Shia individuals on a terror list known as the Awamiya Cell on charges of carrying out armed attacks in the Eastern Province and spying for Iran. Having cracked down effectively on that area, plans were announced thereafter to rebuild Awamiya to make it a tourist and heritage centre.

Others of those executed were primarily found guilty of being criminals. Indeed, of those executed in 2019, 82 sentences were for drug offences and 57 for murder. The use of the death sentence for nonviolent crimes like drug possession signals the importance of social redlines: just because the kingdom is liberalising in some ways does not imply a change in the government's strict position against drugs.

|

Another worrying trend is the number of young people set to be executed |  |

Another worrying trend is the number of young people set to be executed. The ESOHR is currently tracking the cases of 52 individuals on death row (though there are likely more) and has revealed that, troublingly, 13 children are included on the list for execution. Saudi Arabia executed six young men under 18 in April of last year in a mass execution of 37 people in total, all charged with terrorism and most of whom also were members of the Saudi Shia population.

Prevailing concern about activism about young Saudi Shia men in the Eastern Province likely will continue to drive such moves against young people who remain dissatisfied with MbS's reforms.

Meanwhile, popular Sunni Islamist figure Salman al-Odeh remains in prison and may face the death penalty as well if the government wants to take the same tack against Sunni Islamists as it has against Shia activists.

Arrested in 2017 shortly after tweeting a prayer for reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Qatar after the imposition of a blockade against that country, largely due to its perceived support for Sunni political Islam, al-Odeh was held for one year without charges. He was tried ultimately on 37 charges of terrorism in September 2018 at a closed hearing of the Special Criminal Court, and his verdict and sentencing have been repeatedly delayed.

|

The Trump administration has only appeared critical of the Saudis where oil prices are concerned |  |

Two other noted Sunni scholars, Awad al-Qarni and Ali al-Omari, could also face a similar fate. Indeed, rumours circulated last year that the three would be executed after Ramadan.

Further, thousands of political prisoners, jailed for everything from criticising government economic plans to advocating for the right of women to drive, are said to be suffering from malnutrition and severe physical abuse. This pattern is likely to continue if there are no consequences for Saudi Arabia, which is set to host the G20.

Indeed, the Trump administration has only appeared critical of the Saudis where oil prices, rather than human rights, are concerned. As long as the relationship with Saudi Arabia is viewed as one of economic rather than strategic importance, it is unlikely that the kingdom will be held to account.

Dr Courtney Freer is a research fellow at LSE Middle East Centre.

Follow her on Twitter: @CourtneyFreer

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News