The rise and fall of political Islam and democracy in the Middle East

The euphoria that surrounded Arab and Turkish Islamic political parties’ participation in national elections in the early 1990s has dissipated. Since then, strongman regimes in Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Sudan, the Gulf States, Turkey, and elsewhere have muzzled these parties, eviscerated the electoral process, and jettisoned democracy as the basis for governance. In addition, US policymakers have generally been skeptical about political Islam and often worked to undermine it.

The decision by the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and its ideologically affiliated political parties in the region to enter national elections was a strong signal to Muslim publics that Islam was not inimical to democracy and that political reform and change could occur gradually from within without resort to violence. These parties signalled to their publics that mainstream political Islam could be a catalyst for change as a mediating structure between the state and society.

"Arab autocracy with outside support has failed to secure real stability in their countries or to raise Arab peoples from poverty, let alone advance freedom and democratic governance"

Many of these parties were already providing social, medical, economic, and educational services to their publics which the state has been unable, unwilling, or slow to deliver. The MB and its affiliated parties across the region - from Turkey to Morocco and Egypt - made a strategic decision to participate in elections despite the perceived undemocratic nature of their regimes.

They viewed their Islam as a moral compass for their daily social and political interactions and as a basis of their worldview. People voted for them in large numbers because they judged them to be more honest and less corrupt than the "palace" political parties and an agent of civil society institutions and services. In my numerous conversations with leaders of some of these parties across the Muslim world, as an academic and intelligence analyst, I got the clear impression that their publics viewed these parties as a source of empowerment for democracy and a promise for a hopeful future.

As one leader told me at the time, mainstream Islam, unlike the puritanical Wahhabi view of divine rule, believed that man-made rule did not contradict Islamic teachings. "One can be both a good democrat and a good Muslim," he said.

When, for example, Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood, Turkey's Refah Party, Jordan’s Islamic Action Front, Tunisia's Ennahda, and Sudan’s National Islamic Front were allowed to run for elections, diverse segments of their populations voted for them. Some votes were cast as a "protest" against regime repression and corruption; others in recognition of the social services that these parties provided to needy citizens; still others reflected the belief that mainstream Islamic parties embodied the best promise for political change.

In contrast with regime-supported ruling parties, most Islamic political parties and movements were the best organised politically and the most authentic representative of their publics. The comparison was most stark in Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia, and elsewhere. At the time, many pro-reform Arabs and Turks and Western observers of the region welcomed the involvement of mainstream Islamic parties in the political process and encouraged a gradual, peaceful process of change.

Opposition to Islamic political engagement

Opposition to Islamic parties' participation in elections and to democracy in general, however, has been massive and destructive and has come from four major sources.

First, autocratic regimes in general opposed fair and free elections because of their animus toward democratic, accountable, and transparent government. Rulers in Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain, Sudan, Turkey, to name a few, believed their rule should not be subject to popular scrutiny through the ballot box. They have always believed that forced obedience through bullets rather than ballots is the best guarantor of domestic stability. They opposed all demands for political change through elections, including those from Islamic political parties.

"The optimistic vision of establishing “moderate” Islamic political systems based on compromise and community inclusion proved illusory and fleeting"

Second, Salafi-Wahhabi ideologues, whether in Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, have opposed man-made constitutions and democratic institutions on the mistaken notion that divine rule was the only legitimate form of government. This is why Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan, for example, have no written constitutions and do not permit fair and free elections.

Third, many Arab and Turkish Western-educated "secularists" also opposed Islamic political parties entering the political fray because they did not trust the sincerity of these parties' commitment to democratic politics. They buttressed their position by a speech given by Edward Djerejian, then-Assistant of State for Near Eastern Affairs, in 1992 in which he declared that political Islam only believed in “one man, one vote, one time” in order to attain power.

|

|

Djerejian’s position, which reflected US policy at the time, initially was sympathetic to political Islam but became more concerned that Islamic parties were using the ballot box only to attain power. Once there, they would work to replace democracy with theocracy. That fear resulted in secularists often lining up behind autocratic regimes and thus inadvertently but effectively thwarting democratic reform.

Some of these regimes often buttressed their anti-democratic position through the brutal use of force against all pro-reform groups, Islamists, and secularists alike. Consequently, thousands of pro-democracy civil society activists languish in prisons across the region to this very day.

Finally, powerful foreign state actors, especially the United States and Israel, which, in collusion with autocratic regimes, have generally been antagonistic toward Islamic political parties. Their underlying assumption was that it’s easier to deal with autocracies than democracies because they worried that any popular input into government policy would be anti-American, anti-imperialist, and anti-Israel.

What went wrong on the road to democracy in the Arab world?

The optimistic vision of establishing "moderate" Islamic political systems based on compromise and community inclusion proved illusory and fleeting. The vision that "moderate Islamists" were key to Arab political reform, as argued in an influential 2005 Carnegie Endowment report, has become a mirage. The legacies of such renowned Islamic reformists as Rashed Ghannouchi of Tunisia, Hassan al-Turabi of Sudan, and Fahmi Huwaydi of Egypt, have been overshadowed by regimes that have deployed “terrorism” laws to suppress pro-democracy advocates. Consequently, political Islam has become so muzzled that it no longer remains a viable agent of political reform and pro-democracy advocacy.

So much has changed in the past two and a half decades on the rocky road toward democracy in the Arab world. And not for the better.

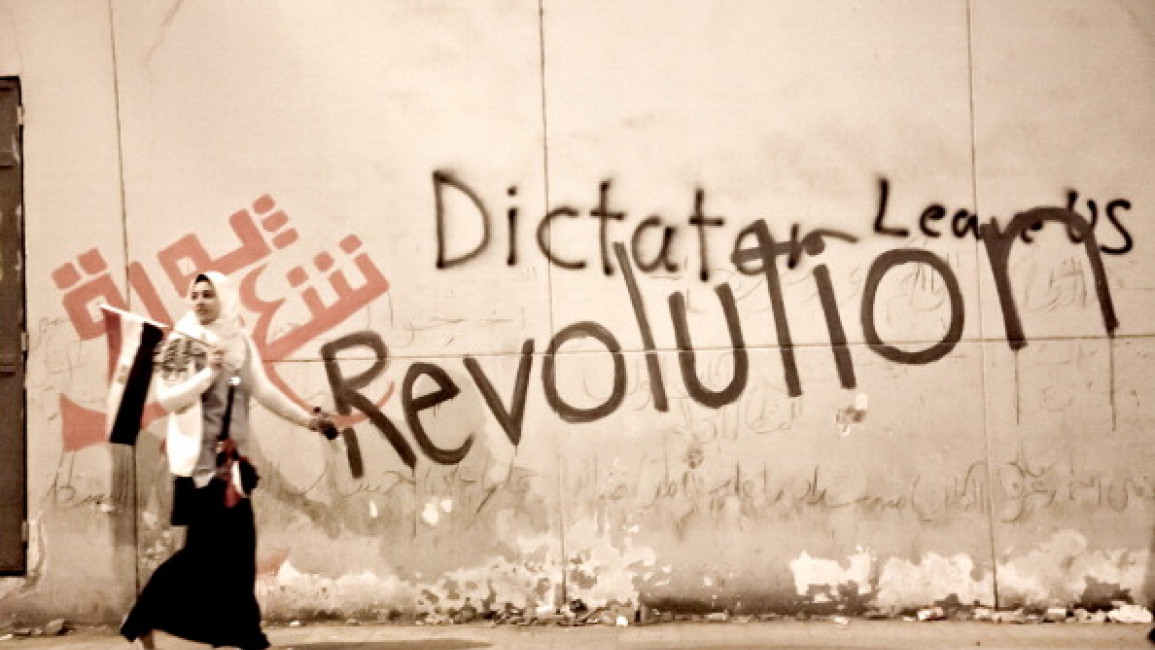

Several autocrats were toppled during the so-called Arab Spring of 2011, but they were replaced by other dictators. Tunisia was an exception but is now regressing dangerously under the new president, Kais Saied. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has used his Islamic party AKP, the Refah Party's successor since the early 1990s, to expand his authoritarian rule. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has replaced Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and Bashar al-Assad has survived the popular uprising in Syria.

The United States, former European imperialist powers, Israel, Russia, and China have all supported Arab dictators in order to serve their interests. But Arab autocracy with outside support has failed to secure real stability in their countries or to raise Arab peoples from poverty, let alone advance freedom and democratic governance.

Yet, these actors, including the dictatorial regimes they have supported, are no more secure today than they were when Arab civil society was vibrant and Islamic political parties were involved in electoral politics. Many Arab states - whether run by autocrats or corrupt billionaires, as in Lebanon - are fragile and likely will implode. Arab states as well as external powers will certainly be affected by the fallout. Internal social unrest could easily spread across the region and beyond.

This depressing state of affairs demands that the United States and other actors reconsider their support of Arab dictators and replace their generous supplies of bullets with a renewed commitment to ballots. Ultimately, that is the only way long-term stability, security, and possibly democracy can be achieved.

Dr Emile Nakhleh was a Senior Intelligence Service officer and Director of the Political Islam Strategic Analysis Programme at the Central Intelligence Agency.

He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a Research Professor and Director of the Global and National Security Policy Institute at the University of New Mexico, and the author of A Necessary Engagement: Reinventing America’s Relations with the Muslim World and Bahrain: Political Development in a Modernizing State

Follow him on Twitter: @e_nakhleh

This article originally appeared on Responsible Statecraft.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.