Restating Orientalism: A welcome critique of Said's classic

The publication of Said's Orientalism in 1978 sent shockwaves throughout the academic and media world. Although primarily focused on western representations of the Middle East, the book became popular across the non-western world, being taught in India, China and elsewhere.

Orientalism was fundamentally a critique of Western imperialism, it examined the way writers, academics, journalists, artists and scholars produced knowledge and images of non-West (especially Arab) cultures, politics and societies, in order to serve colonialists in the pursuit of subjugation of non-Western peoples. The ideas and images they produced, according to Said, were a misrepresentation of these peoples which have caused harm to them.

The group of scholars dedicated to this knowledge (mis)production were traditionally called 'orientalists', hence the title of Said's book. Orientalism sent those who study non-Western cultures into crisis and, following the success of Said's publication, the term 'Orientalist' became a pejorative term as it came to mean someone who was a racist and/or imperialist.

|

|

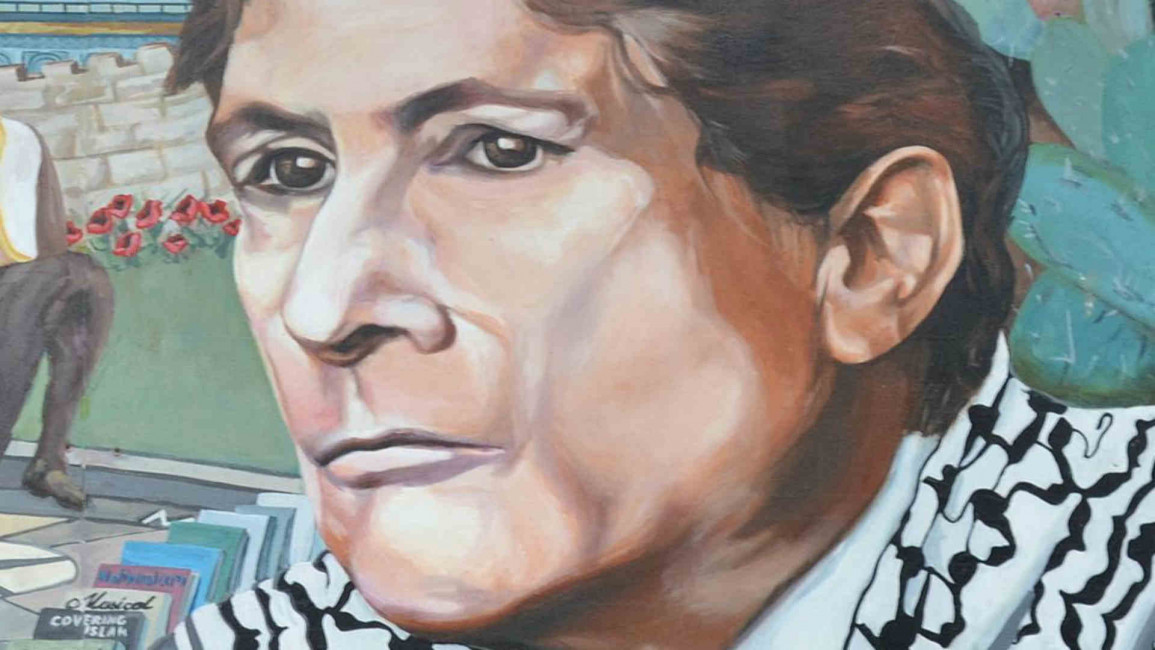

Like most people who have studied the history and politics of the Arab world, I have always been grateful to Edward Said for the space he opened up in critiquing the way the Middle East and Islam is discussed.

For many, Said's book is liberating and it has allowed them to challenge the stereotypes and prejudices they encounter - and that is a good thing. However, I have started to have anxiety over some of the ideas that Said comes to represent; Said's ideas are very much part of postmodernism and the postmodernist movement does not believe in "truth".

Indeed, postmodernism treats truth with suspicion - objective truth is non-existent, there is but subjective truth and that is to say "my truth" and "your truth" which are both equal. There is no absolute truth.

The postmodernist approach to truth is eagerly taken up by dictators, despots and extremists movements. The idea of a post-truth "fake news" world is a by-product of such thinking. It should go without saying Edward Said is not responsible for "post-truth" but many of his intellectual influences most certainly are.

The anxiety over Said's ideas and influences draw me towards those examining them; enter Wael Hallaq and his book. Hallaq is an interesting figure, an American professor of humanities at Columbia University, a proud secular humanist, much like Edward Said, from a Palestinian Christian family who specialises in Islamic Sharia, or law.

It was researching Sharia as public law that I first encountered Hallaq and his book The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity's Moral Predicament, in which he argued that Sharia was better suited for civil society and democracy than modern state law, but Sharia was poorly suited for the modern state system with its centralising power dynamic.

If anyone is going to provide a nuanced and well thought-out critique, it would surely be Professor Hallaq.

Restating Orientalism is a labour of love and Professor Hallaq is clearly very fond of Edward Said and his intellectual insights. He values Said's contributions, his book is not an anti-Said tirade. However, there are very real issues with the way Edward Said conceives of Orientalism as a field of study - as Hallaq notes, Said's critique can be "incoherent".

Said treats orientalism as a timeless monolith that can be traced back to Ancient Greece and continues until the present day. The claims by Said are startling and make no sense from a historic point of view, according to Hallaq.

On top of this, Said develops no theory of his own about what the Orient is or how to study it, - he levitates between different critiques within orientalism to make his case and ignores the divergences within the orientalist field of study. He will pluck examples out of their original context from one century and find another example from a different century and he will put them together as part of his supportive argument.

Twitter Post

|

Said sees Orientalism as constrained by geography and not intellectual pedigree, a White English male and a Jordanian woman could make the same argument and come to the same conclusions about the status of women in Islam, for example, yet only one of them is engaged in Orientalism, according to Said.

Methodologically this is all over the place, and as Hallaq argues, Said's field of study was English literature and he had no historical training. Hallaq demonstrates that Orientalism is a modern field of study, not an ancient one, that has produced a complex range of thinkers and scholars; he does not deny that some were imperialists much as Said describes, but he also shows Orientalists who were subversives to the imperial project and to fellow Orientalists - and that such figures were not nominal but highly influential.

Said ignores or downplays them and their role. At the heart of Said's critique is a tension, according to Hallaq. Said is thoroughly liberal, modern, western and secular and has a disdain for religion and tradition, and he has no interest in Arab and Islamic culture.

This disdain is key to understanding Said's critique of Orientalism; Said downplays the modernity of Orientalism in favour of ancient roots because Said himself is fond of the European enlightenment and its modernist project.

He tries to isolate Orientalism from the values of the Enlightenment and this bias shapes Said's approach. Hallaq offers welcome and much needed critique of one of the key ideas defining the East-West relationship and should be required reading.

Usman Butt is a multimedia television researcher, filmmaker and writer based in London. Usman read International Relations and Arabic Language at the University of Westminster and completed a Master of Arts in Palestine Studies at the University of Exeter.

Follow him on Twitter: @TheUsmanButt

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.