Press freedoms in Tunisia: Undoing revolutionary gains

The principle gains won by the 2014 revolution in Tunisia were freedom of speech, freedom of information and freedom of the press. Once a tightly controlled sector, it saw the restructuring of public media and the sudden birth of multiple online news outlets as well as tv channels. The implementation of a legal framework through decree 115/2011, further protected these gains.

Indeed, the revolutionary nature of such an evolution within the media sector, and the subsequent protections introduced, cannot be overstated after decades of dictatorship.

Now, these gains are under threat and the state of press freedoms in Tunisia is alarming according to the National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists (SNJT). The union warned that this has been the case since sitting president Kais Saied’s July 25 coup, which allowed him to gain ‘all the power’.

However, the hostility towards a liberated Tunisian press did not start with Kais Saied in the post-revolution context. His predecessor Beji Caid Essebsi, a long time servant of the Bourguiba regime and president of Tunisia between 2014 and 2019, was also problematic on the subject.

''State violence – expressed both by its institutions or street mobs – against journalists, is the direct result of presidential contempt in the absence of widespread popular backing. It is the reason Saied feels threatened by independent journalism: it exposes the impasse the country is in under his watch.''

Though elected to facilitate the transition towards a more established democracy, Essebsi directly attacked the media by accusing them of tarnishing Tunisia’s image abroad – an accusation that has been used repeatedly as a repressive political tool by successive governments. When in 2018, journalists were harassed for covering national demonstrations that were sparked over the heightened cost of living and taxes, it happened under Essebsi’s leadership.

Police even arrested and questioned French journalists, Michel Picard from Radio France International (RFI) and Libération’s Mathieu Galtier.

The events in 2018 normalised a more violent approach to journalists who would expect intimidation whilst covering demonstrations. There were even calls to use “rape” against them, from within the Police Union.

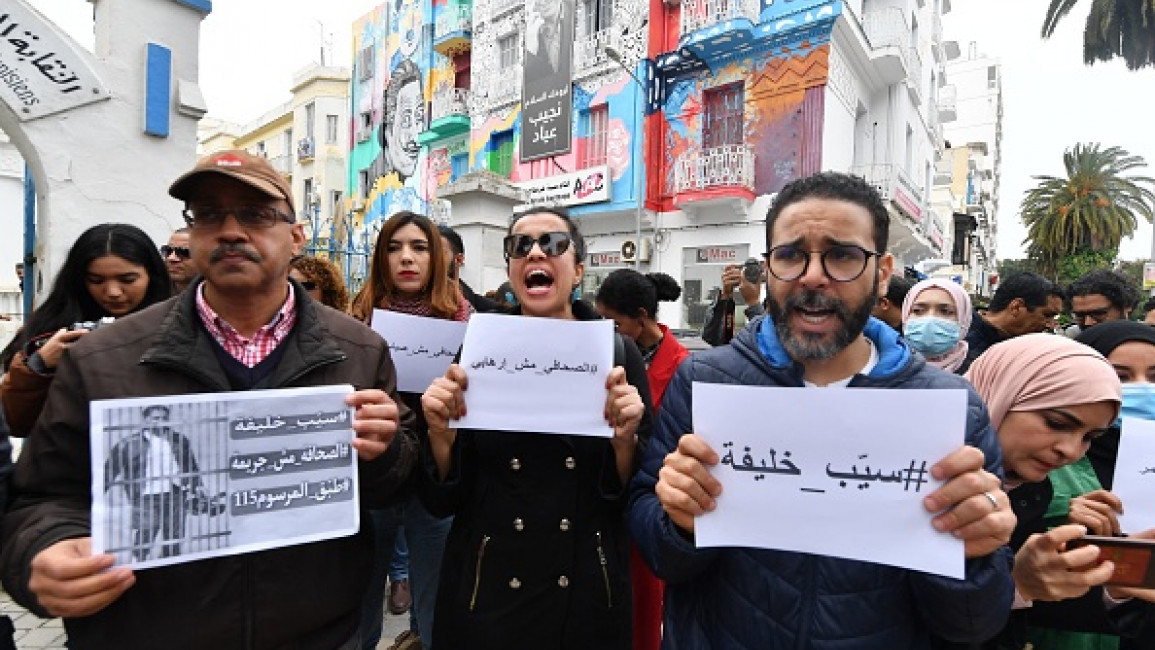

Journalists fought the growing state hostility against them and rallied in Tunis to express their opposition to what they feared was an ushering towards the return of a police state.

By the time Saied dissolved parliament and dismissed the PM, demonstrators were targeted and physically assaulted. The July 25 movement was perceived as a hurdle to the president’s power grab, and was treated as such.

During his term, Saied pursued the control of Tunisian press. In April 2021 he appointed Kamel Ben Younes, known for his pro Ben Ali track record, as director of the Tunisie Agence Presse news agency. The opposition from journalists worried over their freedoms was met with the police raiding the building to enforce the decision.

Saied didn’t stop there. Nessma TV and Zaytouna TV were shut down for allegedly operating without a license, but it was understood that they were targeted for allowing dissenting voices to express opposition to the president on their platform.

The SNJT once more expressed its worries.

This is all perhaps unsurprising given Saied’s rule not only began with a coup, but was followed by him ordering a police raid on the Al Jazeera offices in Tunis and their subsequent shutting down.

Photojournalist from Tunisie Afrique Press, Hamza Kriistou, was also targeted, as was Walid Abdallah from Al Arabiya and the New York Times’ Vivian Yee and Massinissa Benlakehal.

State violence – expressed both by its institutions or street mobs – against journalists, is the direct result of presidential contempt in the absence of widespread popular backing. It is the reason Saied feels threatened by independent journalism: it exposes the impasse the country is in under his watch.

Press freedoms are further restricted through the country’s increasingly hostile legal framework. The government sent a decree to all its ministries announcing that it will enforce the power to pressure journalists into revealing their sources and – in an effort to control what the public is told – to oblige officials to seek an official authorisation before speaking to the media.

With the media sector being so dependent on advertisement, the Tunisian press is forced to ‘follow the money’ just to survive. Furthermore, the lack of transparency within institutions plays a big role in undermining its future. The case of media tycoon Nabil Karoui speaks volumes. His arrest for money laundering added doubts on the impartiality of Nessma TV, which he owned, and more broadly towards the media which enjoy a measly 66% of the public’s trust.

Appropriately, Tunisia fell from the 73rd to the 94th place in Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) World Press Freedom Index.

Prominent figures of Tunisian journalism, like Mohammed Yassine El Jelassi, are rightly holding the president responsible for the deterioration of the working conditions of journalists and the free access to information.

Kais Said’s “reform through dictatorship” gave him monopoly of all three branches of power. It also laid the foundations for a long term weakening of all that Tunisians gained through the uprisings since 2014. Three judges and the former prime minister have gone on hunger strike over his ongoing purge of institutions.

Tunisia’s former dictators Bourguiba and Ben Ali would not have lasted had it not been for the targeting and repression of journalism. The revolution, which was made up of fearless and independent reporters like Lina Ben Mhenni, defied decades of censorship to speak truth to power. Now, it seems the state is creeping back to its former practices. Tunisians must therefore decide whether they want to mortgage their future on the basis of a single man’s ambition to rule unrestrained, or fight for the freedom of its press.

Yasser Louati is a French political analyst and head of the Committee for Justice & Liberties (CJL). He hosts a hit podcast called "Le Breakdown with Yasser Louati" in English and "Les Idées Libres" in French.

Follow him on Twitter: @yasserlouati

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News