A new era of uncertainty for Turkey

To most people who voted on Sunday's constitutional referendum, a new dawn has broken over Turkey.

However, it is the beginning of an uncertain new era, with Turks split almost completely down the middle into those who believe that Turkey's transformation into an executive presidency will herald a rejuvenation of the republic, and those who believe that it is the beginning of an era of authoritarianism.

Over the past week, I have spoken to voters from both the "Yes" and the "No" camps. I have watched their campaigns on television, and listened to the party leaders' speeches, and witnessed all the controversies that usually spring up around such pivotal votes.

Although President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has emerged victorious in yet another popular vote, it was by the barest of margins - a little more than 51 percent - and this is likely to foment even greater divides in an already fractious Turkish polity.

Ataturk's legacy

As someone who was also involved in another historic referendum recently, the Brexit referendum that saw Britain vote - again by a hair - to leave the European Union, the divided and polarised reactions to Turkey's referendum result are familiar to me.

Just as in the aftermath of Brexit there was jubilation as well as protests against the parties that led the campaign for the winning camp, similar scenes played out across Istanbul and other cities last night.

Ultimately, however, Brexit did not fundamentally change the governing system in the United Kingdom, but primarily impacted upon legislative and economic matters, while also having a social impact.

|

Although President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has emerged victorious in yet another popular vote, it was by the barest of margins |  |

In Turkey, on the other hand, the parliamentary system that has been in place for decades that vested executive power in the hands of a prime minister with a largely ceremonial president, has now been completely upended.

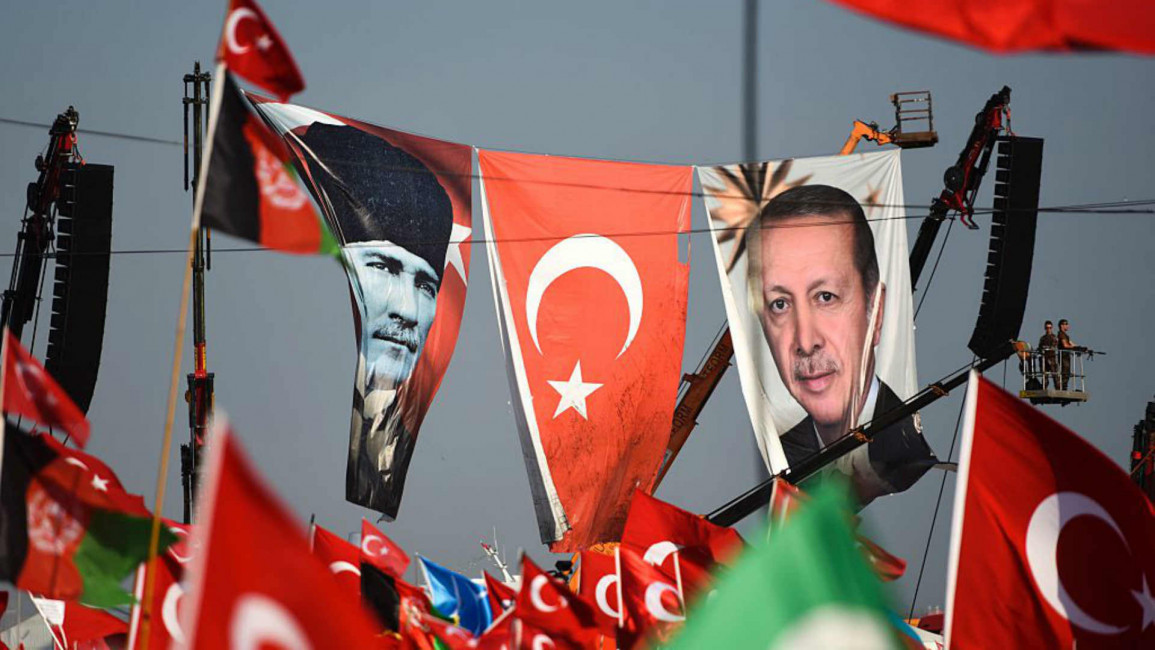

Many in the "No" camp argued that Erdogan - viewed as an Islamist despite insisting on his secularism – was killing the secular democratic legacy of founding father Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

However, a comparative examination of history will show that there are many fundamental similarities between the system and method of rule utilised by Ataturk and his successors, and the system of governance soon to be in place under Erdogan.

After the Turkish republic came into being in 1923, its new constitution adopted in 1924 focused legislative powers in the parliament, while executive power was wielded by Ataturk as president of the republic, with the prime minister appointed by the president.

| Read more: Post-referendum Turkey extends state of emergency, seeks capital punishment | |

Ataturk reigned over a period of a one-party state headed by the Republican People's Party (CHP), which was inherited by his successor Ismet Inonu following Ataturk's death in 1938. A multi-party democracy did not properly exist until the elections of 1950, and then only following international pressure following on from World War II.

Multiple coups led by Kemalist officers - who had appointed themselves guardians of Ataturk's legacy – toppled a series of governments, including executing Adnan Menderes, Turkey's first freely elected prime minister in the putsch of 1960.

|

Erdogan appears to have come closest to restoring Ataturk's legacy |  |

The current constitution was adopted in 1982 following a coup led by general-cum-president Kenan Evren in 1980 that weakened the office of the president and empowered the prime minister, while setting the stage for a Turkish parliamentary system that was often plagued by indecisive coalition governments.

With yesterday's vote now paving the way to the restoration of power to an executive presidency, a system that existed in the early days of the republic, if anything, Erdogan appears to have come closest to restoring Ataturk's legacy – at least from a governance perspective, if not ideological.

A key difference between Ataturk and Erdogan is that Turkey is not a one-party state under AKP, but still appears on course to continue as a multi-party system.

Too much power

While the protestations that Erdogan is killing off Ataturk's political vision can thus be discounted as a way of drawing upon the voiceless symbol that Ataturk has become to fight an ideological battle against Erdogan, there is much merit to the more institutional and structural arguments posited by the "No" campaign.

For instance, by having parliamentary and presidential elections on the same day, it is a near certainty that whoever becomes president will also dominate parliament by being the leader of the party with the most seats.

The president will thus not only wield executive power, but will have significant influence over the legislative functions of the state.

While some argue that making the president criminally liable and removing the current immunity he enjoys will check any shift to authoritarianism, it is a stretch to believe that a parliament dominated by the party which is in power will have the ability to muster enough lawmakers' votes to impeach a president.

|

It is likely that it was the loyalty that Erdogan's personality and charisma inspires that allowed the vote to pass in the first place |  |

This is especially so in Turkey, with a political culture that often favours strong party leaders who have a near-total draconian level of control over their parties.

While those who voted "Yes" on Sunday may trust Erdogan with such powers - saying that it is necessary to stabilise the country and secure it from political and economic turmoil leading to insecurity - would they be equally as comfortable with a CHP president at the helm?

I doubt that, and it is likely that it was the loyalty that Erdogan's personality and charisma inspires that allowed the vote to pass in the first place.

Any other modern Turkish leader asking for such power would have surely been given short shrift.

The immediate danger now lies in the fact that almost half of the country is almost entirely against Erdogan and the new constitution, which could spell political turmoil and greater instability all the way up until the issue is laid to rest, one way or another, in Turkey's first presidential election under the new constitution in 2019.

Tallha Abdulrazaq is a researcher at the University of Exeter's Strategy and Security Institute and winner of the 2015 Al Jazeera Young Researcher Award. His research focuses on Middle Eastern security and counter-terrorism issues.

Follow him on Twitter: @thewarjournal

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.