My brush with fame: Meeting Nasser in 1965

It was the summer of 1965 and I was an intern in Cairo's Nile Hilton Hotel. It was then the only five-star hotel in Egypt. It served as the government's principal guest house after its opening some seven years earlier.

In the interim it had hosted such dignitaries as Vice-President Richard Nixon, after whom the best suite on the top floor had been named; the boxer Muhammad Ali who was celebrating his conversion to Islam and name change by coming to Egypt; and various heads of state from African and Asian countries, including leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) who had attended its summit meeting the previous October.

Indeed, it was the following NAM summit that resulted in my meeting Nasser by the Nile. In the October meeting, it had been decided to exclude the Soviet Union from the organisation. Pushback from Moscow had caused Nasser and his allies within the NAM to agree to meet again in Cairo in mid-June to plan a joint strategy, before then proceeding to Algiers for the meeting scheduled to commence on June 29.

On June 15 or 16, we front desk clerks were called to a briefing by the hotel manager about the imminent arrival of Nasser's guests, including Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, North Vietnamese Foreign Minister Lee Duc Tho and Indonesian President Sukarno. Their arrivals were anticipated to begin the following day and would be occasioned by visits to the hotel by President Nasser.

We were ordered to reply until further notice to any immediate requests for rooms by saying the hotel was full, to anticipate working extra shifts, and in general to be on our best behavior and wearing our best suits.

|

He walked over to the front desk, reached out his hand, said welcome to Egypt, and asked who I was |  |

Events in Algiers then derailed Nasser's plans. On June 19 the army, led by Colonel Houari Boumedienne - and possibly instigated by Moscow in an attempt to derail Nasser's plans to use the summit to confirm its exclusion from the NAM - overthrew President Ahmad Ben Bella.

The following day, the army and police put down student and worker protests, but the country remained tense and seemingly unstable.

Back in Cairo, confusion set in. It was not clear whether the military would consolidate the coup and, if so, whether Nasser and his illustrious allies should proceed to the June 29 summit as planned. As it transpired, these NAM dignitaries waited for about a week before collectively deciding to call off the summit and head home.

So for a week not only were these and other leaders staying in our hotel, but Nasser was coming and going to meetings with them. The front desk was immediately to the left of the main door into the hotel on the Nile River side. It was my good fortune to be on duty the very first day Nasser arrived in mid-morning to meet his earliest arriving guest, who was President Sukarno.

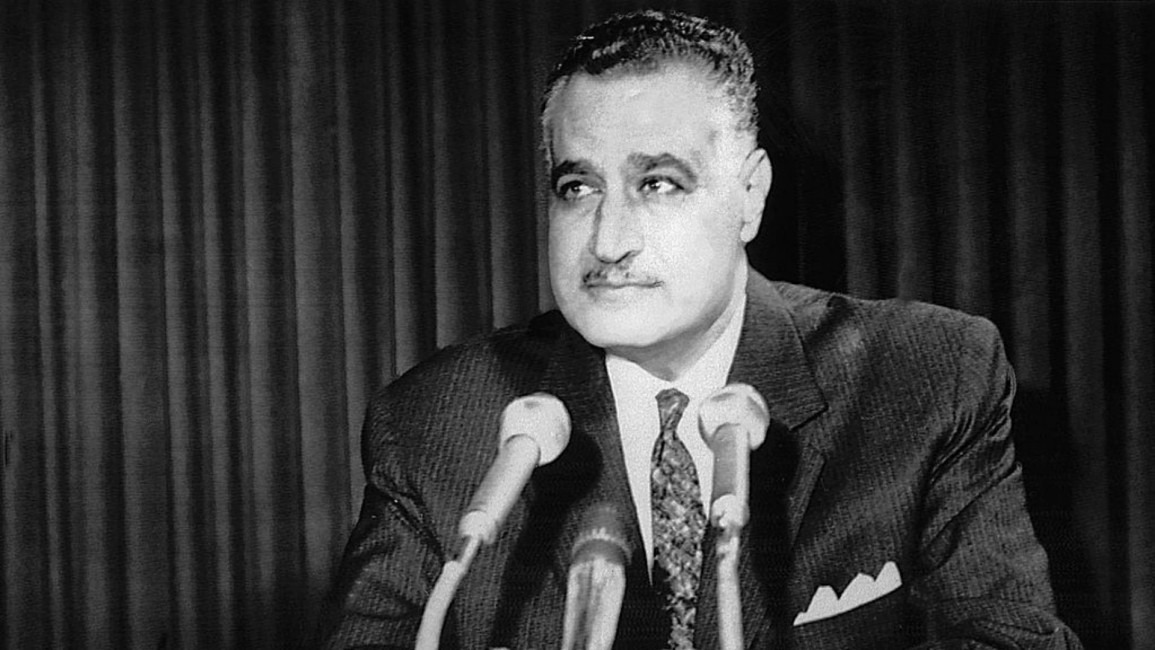

Nasser was surrounded by a phalanx of security personnel, but his height, combined with what seemed to be an unusually large head and face, upon which was a beaming smile, caused him to stand out. The TV cameras were whirring away.

Amazingly, he looked in my direction and apparently perceiving me as an American, or at least a foreigner, must have wondered what I was doing there - if he had not been briefed. So he walked over to the front desk, reached out his hand, said welcome to Egypt and asked who I was.

I explained that I was an American from Minnesota, interning for the Hilton chain and that it had been my good fortune to be assigned to Cairo. He asked what I thought of Egypt and as I recall I responded in rather stupid, embarrassed fashion, saying it was wonderful but hot. He then carried on to the elevators and ascended.

|

With a smile, Nasser introduced me to Sukarno as an American working for the Egyptian government |  |

An hour or so later he descended into the lobby with President Sukarno at his side, flanked by the TV crews. As they were passing by the front desk en route to the waiting cavalcade of limousines, he came over again, and with a smile introduced me to Sukarno as an American working for the Egyptian government.

The hotel was, in fact, owned by Egypt with Hilton having a service contract that included use of the name. So technically he was correct.

The point he was presumably seeking to make was that Americans were welcome in Egypt, despite the recent sharp deterioration in Egyptian-US relations. The previous Thanksgiving, an unruly crowd a few hundred metres away had broken into the library of the United States Information Agency, immediately next to the US embassy, and set fire to it.

The Johnson administration accused the government of Egypt of failing to protect US diplomatic institutions, with the widespread belief in Washington that Nasser's security services had organised the assault. The Senate had responded by suspending shipments of Public Law 480 wheat to Egypt, at a time when the US government was well aware that Nasser's foreign currency reserves were desperately low.

And indeed, less than four months after my encounter with Nasser, he replaced Soviet-leaning Ali Sabry as prime minister with Washington-leaning Zakariya Muhyi al Din.

Presumably by the summer of 1965 he was already contemplating an effort to repair relations with the US.

In any case I appeared with Nasser on the evening TV news programmes, but that was not the end of my dazzling introduction to Egyptian political life. Twice more in that week Nasser shook my hand when passing by the front desk.

The day after my initial encounter with him and Sukarno, I looked across the lobby and there was the latter, looking over at me while sitting on a sofa. He beckoned me to come over, which in violation of front desk rules I immediately did. Tea was brought and he asked me about myself and suggested I come to Indonesia to see what fine things were happening there.

|

All rooms in the hotel were bugged. The central listening station was just behind the front desk |  |

He was remarkably jovial and relaxed for being a head of state cooling his heels for an unknown period far from home where he may have had some inkling that the following year's coup was already being plotted against him. Some days later I discovered why he may have been so content.

All rooms in the hotel were bugged. The central listening station was just behind the front desk, with security personnel coming and going through a back door. One of those officers, Yusuf, a major in military intelligence, had been assigned as my principal minder, which meant that he tailed me on my nights out.

Eventually realising this, I approached him to share a Scotch with me rather than drink Spathis water - as the local soft drink was known - at another table. So began a friendship that lasted until I left Cairo. In 1966 Yusuf was dispatched to Yemen, where he was killed in action.

Egypt and the world lost to that senseless war a wonderful guy who relished the secrets of the world he surreptitiously watched. While Sukarno was staying in the hotel, Yusuf invited me into the "secret" listening room, where he was eavesdropping on the Bung and his lady companion, who was not his wife. She had, at his request, been installed in her own room on another floor.

His companion was the hotel's well-known belly dancer, who Yusuf informed me had been seconded to this duty by none other than Nasser himself.

I also met and spoke with Zhou Enlai during those remarkable few days.

But it was Nasser who captivated not only me, but everyone else in the hotel. It was not just because he was an Egyptian among an overwhelmingly Egyptian audience. It was also not just because he gave the impression of being a magnanimous host, in more ways than one.

It was because he exuded charm and magnetism the minute he entered a room. He literally and figuratively stood out above others, clearly the centre of attention, but with a demeanour that seemed to suggest modesty, even curiosity.

He spoke English very well and seemed of quick intelligence, as his either planned or spontaneous decision to introduce himself to me suggests. I shall never forget that brief encounter and, for me, the amazing events in that June week of 1965.

Robert Springborg is Kuwait Foundation Visiting Scholar at Harvard University’s Middle East Initiative, Belfer Center. He is also Visiting Professor in the Department of War Studies, King’s College, London, and non-resident Research Fellow of the Italian Institute of International Affairs.

He has innumerable publications, including Mubarak's Egypt: Fragmentation of the Political Order; Family Power and Politics in Egypt; Legislative Politics in the Arab World (co-authored with Abdo Baaklini and Guilain Denoeux), Oil and Democracy in Iraq; Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, ‘Islamic’ and Neo-Liberal Alternatives, among others.