Islamic State - the best of enemies?

Islamic State - the best of enemies?

Comment: The collapsing 'caliphate' has exposed the significant differences between American and Russian visions for Syria, writes James Denselow.

5 min read

What will Trump decide to do once IS in Syria have been defeated? [AFP]

It has been a roller coaster week for US-Russian relations when it comes to the conflict in Syria.

On Saturday at the margins of the APEC Conference in Vietnam, both countries' presidents met and subsequently issued a joint release that confirming their joint determination to 'defeat ISIS in Syria'.

Such a rallying call seemed disconnected from events on the ground, where Islamic State have rapidly lost city after city and are now a shadow of their former strength. The statement pivoted to the more substantial issues of the Syrian Geneva peace process, and stressed the need to both implement existing UN resolutions and respect the continued territorial integrity and unity of the country.

Yet the facade of Syrian sovereignty is a world away from the reality of a country awash with foreign militaries, air forces, proxy allies and non-state actors. It took President Erdogan of Turkey to shatter this illusion, when he made the point that countries keep saying there is no military solution in Syria whilst pursuing exactly that.

Hopes in Moscow and Damascus that Washington was on its way out of Syria were jolted only three days after the Trump-Putin meeting when the US defence secretary, James Mattis, told reporters at the Pentagon that they were planning a longer term presence in the country.

This sparked a furious reaction with Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov accusing the US of abrogating previous agreements and supporting dangerous groups in Syria.

However, attempts to prove this by Moscow went somewhat awry when the Russian defence ministry released 'evidence' that turned out to have been sourced from a computer game.

According to Ankara the US has 13 bases in Syria while Russia has five. The posture of US forces has been directly facing down IS while Russian forces have been engaged in a wider effort to support the Syrian regime. Back in 2015 the US State department accused Russia of only focusing 10 percent of their air strikes on IS, but the election of Donald Trump saw a warming of relations.

On Saturday at the margins of the APEC Conference in Vietnam, both countries' presidents met and subsequently issued a joint release that confirming their joint determination to 'defeat ISIS in Syria'.

Such a rallying call seemed disconnected from events on the ground, where Islamic State have rapidly lost city after city and are now a shadow of their former strength. The statement pivoted to the more substantial issues of the Syrian Geneva peace process, and stressed the need to both implement existing UN resolutions and respect the continued territorial integrity and unity of the country.

Yet the facade of Syrian sovereignty is a world away from the reality of a country awash with foreign militaries, air forces, proxy allies and non-state actors. It took President Erdogan of Turkey to shatter this illusion, when he made the point that countries keep saying there is no military solution in Syria whilst pursuing exactly that.

Hopes in Moscow and Damascus that Washington was on its way out of Syria were jolted only three days after the Trump-Putin meeting when the US defence secretary, James Mattis, told reporters at the Pentagon that they were planning a longer term presence in the country.

This sparked a furious reaction with Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov accusing the US of abrogating previous agreements and supporting dangerous groups in Syria.

However, attempts to prove this by Moscow went somewhat awry when the Russian defence ministry released 'evidence' that turned out to have been sourced from a computer game.

|

Fighting against the black flag of IS conveniently cloaked the bigger disagreements between this unlikely cast of military actors |  |

|

|

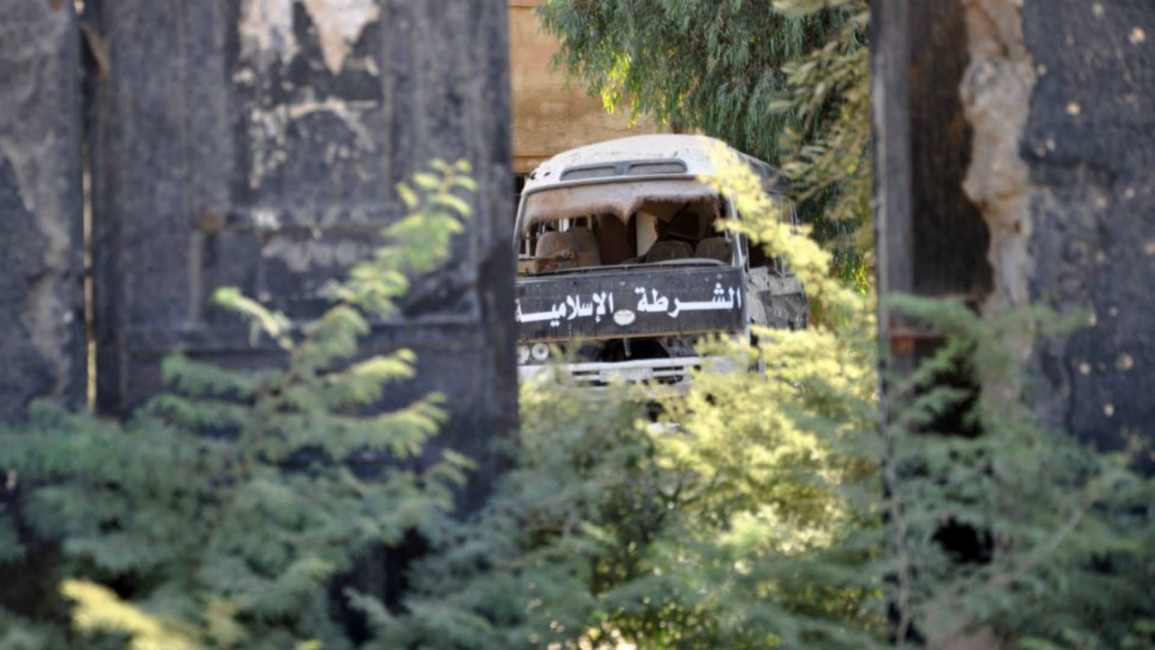

| Destroyed vehicles and heavily damaged buildings on a street in Raqqa, October 2017, after Kurdish-led forces expelled Islamic State group fighters [AFP] |

In April, Trump was polite enough to warn Russia before hitting Syria with cruise missiles, and then in July following meetings at the G20, Trump and Putin announced a ceasefire in the southwest of Syria.

The US president explained subsequently on Twitter that the "Syrian ceasefire seems to be holding. Many lives can be saved. Came out of meeting. Good!".

While Washington claimed that the "de-escalation" zones would not impact their anti-IS operations, the more ambitious roadmap for peace carved out by the Russians-Iranians and Turks at Astana had a mixed record of success, with September the most violent month in the country for the whole year.

IS is the most convenient of enemies.

It lacks direct state-sponsors, deploys extreme violence, and threatens direct or inspired attacks at a global level. The broad coalition pitted against it, including the Americans, Hizballah, Iran and Israel reflects how well IS has made enemies.

Yet fighting against the black flag of IS conveniently cloaked the bigger disagreements between this unlikely cast of military actors. Trump was keen to claim the mantle of victor against IS, in August he tweeted how the US "have made more progress in the last nine months against IS than the Obama Administration has made in 8 years".

However the Russians criticised the US-led operation in Raqqa as almost wiping the city "off the face of the Earth".

But with the fight for IS in Syria almost over, Trump faces tough questions as to what to do next.

The Institute for the Study of War has urged the Trump administration to "constrain, contain, and ultimately roll back Russia and Iran", but there are clear differences between the White House's view and that of other components of the US foreign policy establishment.

Read more: Russia posts video game image as 'irrefutable proof' US helps IS

Indeed, as Trump eloquently said, "when will all the haters and fools out there realize that having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing".

The splits between the US administration in Washington feel a long way away from the proximity of US and Russian forces and their allies on the ground and in the air over Syria. Despite a telephone "hotline" that is seeing a lot of use, there have been near misses, fire fights and deaths.

Rumours abound of a deal allowing IS fighters to leave Raqqa - a city that the regime in Damascus still considers occupied - and as IS collapses there is a race to secure oil and gas facilities.

The demise of IS poses critical questions for the Americans as to how far they are willing to go to support the areas under the control or influence of their allies in the country.

Washington's strategy to date appeared - at face value - to be limited to counterterrorism, while Moscow's was always about shoring up the government in Damascus.

With IS being removed from the equation, suddenly an absence of shared vision - even a superficial one - feels like a dangerous development, and the upcoming Geneva meetings could have a greater impetus as the powers involved struggle to agree on what they are for in Syria, rather than what they are against.

The US president explained subsequently on Twitter that the "Syrian ceasefire seems to be holding. Many lives can be saved. Came out of meeting. Good!".

While Washington claimed that the "de-escalation" zones would not impact their anti-IS operations, the more ambitious roadmap for peace carved out by the Russians-Iranians and Turks at Astana had a mixed record of success, with September the most violent month in the country for the whole year.

IS is the most convenient of enemies.

It lacks direct state-sponsors, deploys extreme violence, and threatens direct or inspired attacks at a global level. The broad coalition pitted against it, including the Americans, Hizballah, Iran and Israel reflects how well IS has made enemies.

Yet fighting against the black flag of IS conveniently cloaked the bigger disagreements between this unlikely cast of military actors. Trump was keen to claim the mantle of victor against IS, in August he tweeted how the US "have made more progress in the last nine months against IS than the Obama Administration has made in 8 years".

|

An absence of shared vision - even a superficial one - feels like a dangerous development |  |

But with the fight for IS in Syria almost over, Trump faces tough questions as to what to do next.

The Institute for the Study of War has urged the Trump administration to "constrain, contain, and ultimately roll back Russia and Iran", but there are clear differences between the White House's view and that of other components of the US foreign policy establishment.

Read more: Russia posts video game image as 'irrefutable proof' US helps IS

Indeed, as Trump eloquently said, "when will all the haters and fools out there realize that having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing".

The splits between the US administration in Washington feel a long way away from the proximity of US and Russian forces and their allies on the ground and in the air over Syria. Despite a telephone "hotline" that is seeing a lot of use, there have been near misses, fire fights and deaths.

Rumours abound of a deal allowing IS fighters to leave Raqqa - a city that the regime in Damascus still considers occupied - and as IS collapses there is a race to secure oil and gas facilities.

The demise of IS poses critical questions for the Americans as to how far they are willing to go to support the areas under the control or influence of their allies in the country.

Washington's strategy to date appeared - at face value - to be limited to counterterrorism, while Moscow's was always about shoring up the government in Damascus.

With IS being removed from the equation, suddenly an absence of shared vision - even a superficial one - feels like a dangerous development, and the upcoming Geneva meetings could have a greater impetus as the powers involved struggle to agree on what they are for in Syria, rather than what they are against.

James Denselow is an author and writer on Middle East politics and security issues. He is a former board member of the Council for Arab-British Understanding (CAABU) and a director of the New Diplomacy Platform.

Follow him on Twitter: @jamesdenselow

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.