Iraqi refugees forgotten and anonymous in Egypt

The humanitarian consequences of the Iraq war were immense - almost 1.4 million Iraqis fled their country. Before the Syrian crisis of 2011, this was the largest displacement of its kind in the region since the 1948 creation of Israel.

The humanitarian responsibility for such disasters have fallen on the shoulders of Middle Eastern countries while the international community mostly looks on.

According to a 2007 Human Rights Watch report, there were approximately 150,000 Iraqis refugees living in Egypt, the majority of whom arrived between 2003 and 2006.

Living for the most part in Cairo and Alexandria, Iraqi refugees were able to enter on costly tourist visas.

Starting in January 2007, the Egyptian government attempted to limit he number of Iraqis entering the country. They now require a face-to-face interview at an Egyptian consulate to process a tourist visa.

There is no diplomatic post in Baghdad. The war in Syria means it is much more difficult to cross to Egypt.

As of 2013, the UNHCR had only 8,000 Iraqis registered as refugees in Egypt, dropping from just over 10,000 in 2008.

While it is a signatory to the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, Egypt has placed several reservations on personal status, education, rationing and labor legislation, which in effect limits refugees' access to public goods and services.

Legal limbo

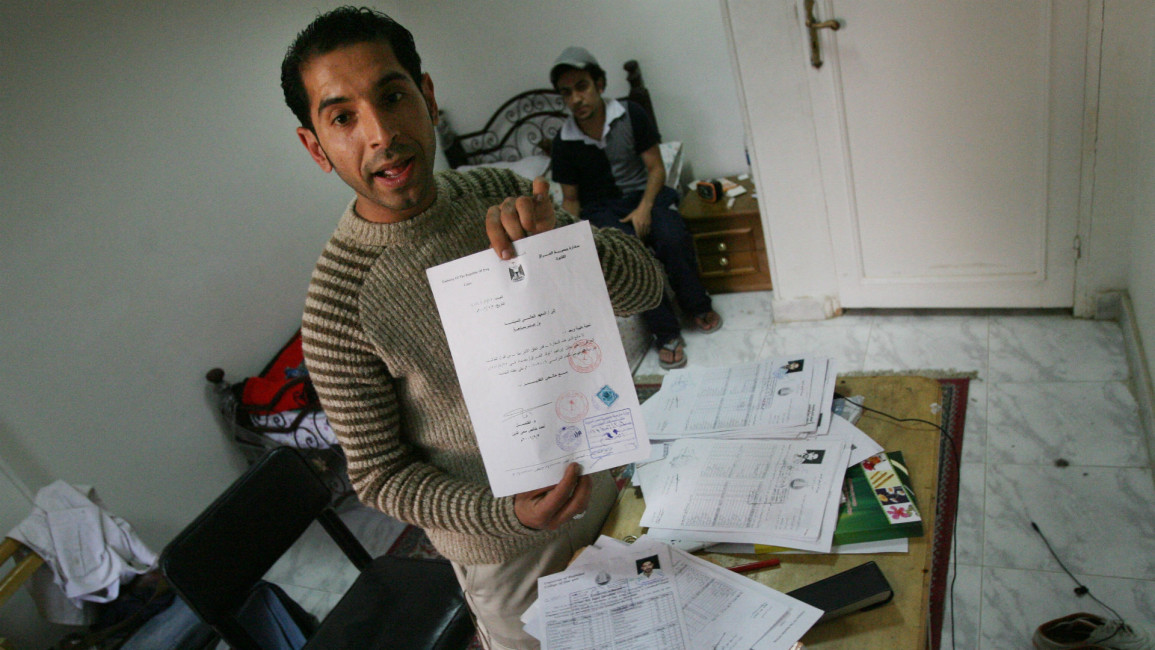

These reservations have affected all refugee populations in Egypt, leaving Iraqis with no legal access to work, limited educational and health services, and no refuge in a country in which they have permanent residence.

One of the only options for a residency, which would enable them to access much needed-services and work legally in Egypt would be to apply for an asylum-seeker yellow card from the UNHCR, which would then have to be verified by the foreign ministry before residency is granted.

Applying for an asylum residency in Egypt restricts the movement of refugees, and makes visits to family members in Iraq almost out of the question.

Egyptian preconceptions that Iraqis are oil-rich and therefore not in need of any assistance has not helped Iraqis feel welcome in Egypt. The ability to increase rent prices for foreigners in Egypt has also left a sour taste in many Egyptians' mouths as they assume that the presence of Iraqi and Syrian refugees is the reason for the rising proces - not the government's mishandling of inflation.

| Iraqi Shia are not only barred from praying in Sunni mosques, but are also denied permission to build their own places of worship. |

While some Iraqis were able to start their own businesses, as is evident in the Giza suburb of 6th of October where the majority of Iraqis in Egypt live, savings are quickly depleted, and what was meant to be a transitory and temporary refuge situation has become a long term problem for most families.

Sectarian strife and divisions have been carried over to Egypt, with Iraqi refugees segregating themselves on Sunni/Shia lines.

According to a 2007 report by the Forced Migration Review, Iraqi Shia are not only barred from praying in Sunni mosques, but are also denied permission to build their own places of worship.

It has been a long and arduous decade for Iraqis in Egypt. The influx of refugees from Syria and South Sudan has created an increased competition for an already limited number of services to both Egyptians and non-Egyptians alike.

The ongoing wars in Syria and Iraq have led many to lose hope in one day returning to their homes. As Egypt remains without an asylum protection program of its own, it relies on agencies like the UN and other international and national organisations to meet people's needs.

Egypt faces an unknown future, with political, security and socioeconomic burdens of its own. The environment it offers refugees is increasingly threatening, and vital organisations that once filled the shoes of its inadequate ministries have been shut down, leaving one of the oldest refugee populations in Egypt to suffer the consequences.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the original author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of al-Araby al-Jadeed, its editorial board or staff.