India is terrorising Rohingya refugees in Kashmir

Other Rohingya refugees describe threats and beatings at the hands of Indian security forces and even private Indian citizens, attacks that have increased in both frequency and ferocity in recent months and years.

When Myanmar launched its most recent crackdown on its 1.3 million Rohingya population in 2017, one that the United Nations has described as "textbook ethnic cleansing", Hindu nationalists and extremists capitalised on India's growing animus towards its 200 million Muslims by whipping up fear of a massive Rohingya refugee influx into the country.

When I spoke with Ashley Kinseth, founder and director of Stateless Dignity, a human rights advocacy group for stateless people worldwide, she told me how government officials in the Jammu region of Indian-administered Kashmir have even advocated for an "identify and kill" movement, one meant to single out Rohingya Muslims and then murder them as a form of what can only be described as a deranged form of hyper-nationalist vigilante justice.

"What really struck me is the effects that this Hindu nationalist movement is having on the Rohingya Muslims, and it mirrors this global trend towards not only Islamophobia but also nationalism and populism, which is really something that the current Indian prime minister and his political party have drawn on," said Kinseth.

Twitter Post

|

The Indian government estimates there are up to 40,000 Rohingya refugees living in scattered settlements throughout India, largely in the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, and Rajasthan - an estimate that is most likely exaggerated by India's right wing ruling party, BJP, especially given that the UNHCR has documented and registered a total of only 18,000 Rohingya refugees in this country of more than a billion people.

Nevertheless, the persecution and fear these survivors of violent dispossession and dislocation experienced in the country of their birth is now being re-lived in the country they sought sanctuary.

In a single week in mid-January, India used the threat of violent force to push 31 Rohingya refugees out of Indian territory towards Bangladesh, where they were eventually denied entry, and trapped on the "zero line", or rather a "no-man's land" on the India-Bangladesh border, according to Reuters.

Threats and attacks from Indian soldiers and private citizens, alongside rising animus towards Rohingya refugees and Muslims writ large, animus fueled by the current Indian government and its surrogates in the media, has forced more than 1,300 Rohingya refugees to cross into Bangladesh since May of last year, according to Abdul Kalam, Bangladesh's Relief and Repatriation Commissioner.

|

|

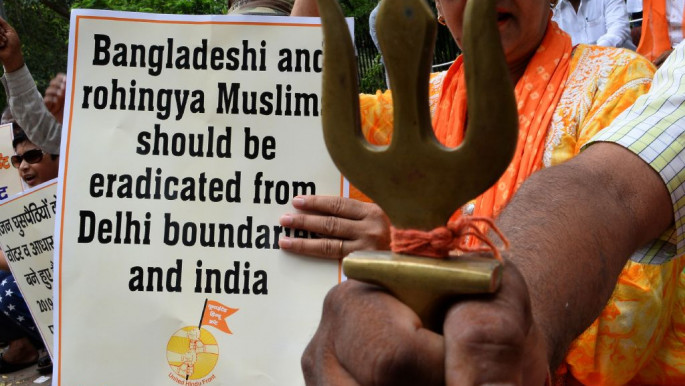

| Members of United Hindu front (UHF) participate in a protest to demand the deportation of Bangladeshi and Rohingya Muslims, New Delhi on 5 August, 2018 [Getty] |

John Quinley, a human rights specialist with Fortify Rights, explained to me how the victimisation of Rohingya refugees in India and Kashmir is occurring on two levels, both nationally and locally.

"Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has characterised Muslim refugees in India as threats to national security," said Quinley. "On the local level, many Indian authorities are not recognizing the UNHCR-issued refugee cards of Rohingya, creating serious protection concerns, and in October 2018, for instance, the Indian government ordered state-level officials to collect biometric data from Rohingya. This process is believed to be part of a government plan to identify and deport all Rohingya from India [and Kashmir]."

Twitter Post

|

"Living in India is not safe anymore," a 39-year-old Rohingya refugee man who had been forcibly relocated from India to Bangladesh told Fortify Rights.

"We have to pay bribes, and the authorities threaten to force us back to Myanmar. My UNHCR card does not help anymore. The Indian authorities came to my house to try to force me to fill out a form with all my biometric information to send me back to Myanmar. After this I was very fearful. I fled."

When I spoke with Satar Nirob, a Rohingya refugee in Kutupalong, Bangladesh, he told me how Rohingya who have fled from India are "doubly traumatised", having been forced from their home villages by the Myanmar military, and now from their shelters in India: "I've met some who can barely speak or eat because the past two to seven years of their lives has been nothing but full of terror and fear."

In fact, India has demonstrably become unsafe not only for Rohingya refugees but also all religious minorities, seemingly, according to a new report published by Human Rights Watch. Since Prime Minister Modi came to power in 2014, more than three-quarters of religiously motivated murders were carried out by Hindus against Muslims, with Indian authorities either delaying investigating these crimes, justifying them, or helping the perpetrators sue the victim's families.

When I asked Quinley what the international community should do to bring security to Rohingya refugees in India and Indian controlled Kashmir, he said it should pressure Modi's government into granting legal status and basic rights to Rohingya refugees living in the country: "The Rohingya are genocide survivors and should be protected."

Clearly, the other UN member states must also do more to resolve this crisis, and it begins by holding those responsible for the genocide accountable and it ends with providing a security guarantee and full citizenship rights to 1.3 million Rohingya Muslims.

CJ Werleman is the author of 'Crucifying America', 'God Hates You, Hate Him Back' and 'Koran Curious', and is the host of Foreign Object.

Follow him on Twitter: @cjwerleman

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News