How the private sector supports Arab authoritarians (part II)

"The murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul was utterly unacceptable. But what do you do? What part do you play in the process of economic and social change?" With these words, Morgan Stanley's chairman and chief executive James Gorman, speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos on January 24, absolved corporate interests of any need to evince concern about egregious human rights abuses or take them into account when plotting business strategy.

Concern for the bottom line over government repression is nothing new, and the Middle East remains a very attractive market. Upwards of $2 trillion-worth of projects in a wide variety of fields are now being planned in the Gulf alone, with construction, transport, and power leading the way; healthcare, education, and technology are also major growth sectors.

Energy projects remain poised for strong expansion as well, with an estimated $1 trillion-worth of existing projects and new development expected to come online by 2023. And, as noted above, arms sales to the region remain a multibillion-dollar industry, with more growth expected as unrest continues in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt and elsewhere, while the possibility of an American-led confrontation with Iran remains an ever-present worry.

The United States has a major slice of the pie: US direct investment in the Middle East totalled $69.13 billion in 2017 and has shown consistently dramatic growth since the turn of the 21st century, wars and revolutions notwithstanding.

International businesses often take into account the possibility of reputational damage if they become too closely involved with bad actors; however, they have demonstrated reluctance to risk their ongoing business relationships in the Middle East.

|

The ambivalent reaction to the Saudi investment conference was something of an aberration; more typically, corporations have quietly argued behind the scenes for business as usual with repressive regimes |  |

International businesses often take into account the possibility of reputational damage if they become too closely involved with bad actors; however, they have demonstrated reluctance to risk their ongoing business relationships in the Middle East by vocally opposing objectionable conduct of governments whose behaviour has outraged the human rights community.

After Khashoggi's murder in October, for instance, a number of prominent international business executives bowed out of Saudi Arabia's Future Investment Initiative ("Davos in the Desert") that month, but many of the companies involved were represented at a lower level and still others attended anyway.

Twitter Post

|

The ambivalent reaction to the Saudi investment conference was something of an aberration; more typically, corporations have quietly argued behind the scenes for business as usual with repressive regimes. In the United States, their appeals are not so much based on specific foreign policy recommendations as on reminding American policymakers, including the White House and Congress, of the money and jobs flowing into US communities and congressional districts from overseas business deals.

In addition to reminding politicians of the value of free-flowing commercial deals, those in the defence industries, backed by tens of millions of dollars in lobbying campaigns and star-studded boards of directors, stress their role in promoting "regional stability" and fighting terrorism. Their implicit message is that US national security interests (and economic growth) are best served by maintaining or improving relations with regional actors regardless of their record on political freedoms and human rights.

The Trump administration has certainly taken this position to heart, and the president's stance on arms sales is a prime example. In April 2018, the administration made a simple change to President Obama's Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, which had forbidden arms transfers to countries committing "attacks directed against civilian objects or civilians".

The new wording of the policy prohibited sales only to countries that undertake such attacks "intentionally". Human rights advocates criticised the change as making it more difficult to successfully oppose arms sales to countries with poor human rights records.

The president has extolled US arms sales to Saudi Arabia for their economic benefits to the United States, explaining his strong reluctance to upend them on the basis of anger over the Khashoggi killing.

He noted in October: "I don't like stopping massive amounts of money that is being poured into our country. I know they [Congress] are talking about different kinds of sanctions, but [the Saudis] are spending $110 billion on military equipment and on things that create jobs for this country. I don't like the concept of stopping an investment of $110 billion into the United States."

Trump's comments strongly echoed similar assertions about the economic value of arms sales to Saudi Arabia he made during his visit to Riyadh a year earlier, a visit during which he pointedly downplayed human rights concerns as an element of US foreign policy toward the region.

Investment flows may work their subtle will in the opposite direction, too. For example, the United States is the top target for Middle East investors in the commercial real estate market. Saudi Arabia alone has become one of the largest investors in America's Silicon Valley, buying into numerous startups and existing firms to the tune of billions of dollars through a variety of funds, including the kingdom's sovereign wealth Public Investment Fund, which is planned to reach $2 trillion in value by 2030. As capital flows into the United States and other countries from such investments, political influence is likely to follow.

International consulting: Technocratic expertise in the service of authoritarian ends

In October 2018 the international consulting firm McKinsey issued a statement saying it was "horrified" after information emerged that a report it prepared for the Saudi government in 2015 on public reaction to economic austerity measures may have been used to identify, and arrest or shut down, leading government critics on Twitter.

The moves against these individuals were a small part of a highly sophisticated and pervasive online effort to discredit or silence critics, including Khashoggi. McKinsey's statement noted "we have seen no evidence to suggest that [the report] was misused". In fact, the McKinsey report was most likely used exactly as intended, if not the way McKinsey thought.

The episode highlights a problem with the international consulting business in general: the lack of accountability for the use or misuse of the intellectual product.

|

International consulting firms tend to shun responsibility for any abuses they may inadvertently support |  |

It is a problem that pervades the international consulting industry in general, and certainly in the Arab region. According to the University of Maryland's Calvert W. Jones, foreign consultants in the Gulf rapidly become co-opted by "local incentive structures characteristic of authoritarian states", subject to the occasionally ruthless whims of their employers. As a result of this - and their own self-perception as neutral technocrats - they quickly "adapt to the incentives: They rarely say anything negative, let alone criticize human-rights abuses (which they see as having little to do with their own work)."

With slight control over the end-use of the information and advice they provide, and a studious disregard for the authoritarian politics of the regimes to which they provide it, international consulting firms tend to shun responsibility for any abuses they may inadvertently support.

As the author Duff McDonald, speaking of McKinsey business practices, told The New Yorker, "they take no responsibility for the result. They are saying to the client, 'You can have all the credit you want, but you cannot push a bad outcome on us'."

Twitter Post

|

Helping state censors do their job

In late December, Netflix abruptly pulled an episode of its stand-up comedy series, "Patriot Act With Hasan Minhaj", from the lineup available to stream in Saudi Arabia. The episode was sharply critical of Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his alleged involvement in the Khashoggi killing, as well as of American ties to the Kingdom.

Netflix acted after an official request from Saudi Arabia's Communications and Information Technology Commission, which said the episode violated Saudi cybercrime law, which bans "material impinging on public order, religious values, public morals, and privacy, through the information network or computers". Netflix issued a statement acknowledging that it "removed this episode only in Saudi Arabia after we had received a valid legal request - and to comply with local law", but that wasn't enough to mollify critics.

Netflix's cooperation with the Saudi censorship regime drew immediate condemnation from The Washington Post, Amnesty International, and others.

The incident highlights a subtle but pervasive problem: corporate collusion with authoritarian states to suppress free expression and unpopular views. In 2017, Snapchat removed Al Jazeera's stories and video from the Saudi Arabian version of its app, prompting the Qatari-owned media company to complain that the US firm's "alarming" move could encourage countries to silence dissent by using their clout with social media and content distributors.

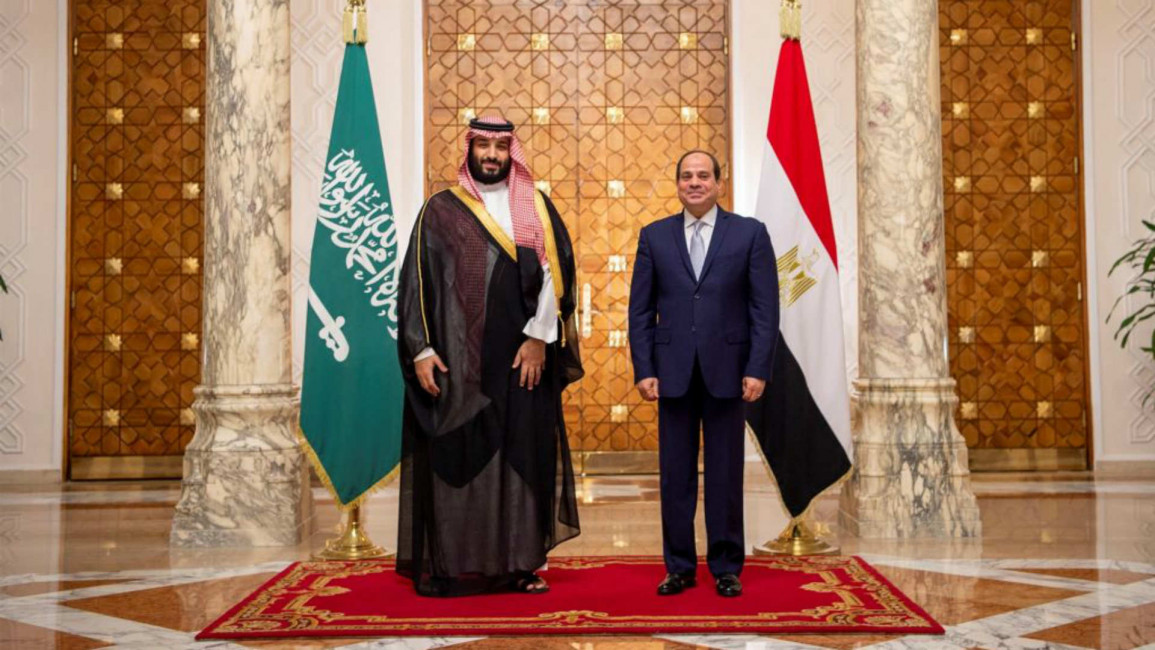

Twitter closed the account of prominent Egyptian activist Wael Abbas, responding to an online campaign against him likely instigated by Egypt's government and its army of online trolls. This tactic has been utilised against other Egyptian social media users as well, a fact of which President Abdel-Fatah el-Sisi boasted in 2016. Further, many countries employ vague or excessively legalistic language to suppress online expression; Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia - an electoral democracy - all use various forms of law, from statutes prohibiting demonstrations to anti-terrorism laws and defamation regulations, to crack down on cyber speech.

Foreign companies operating in their electronic space may be asked, or obliged, to go along, as was the case with Netflix.

Cooperation with the architecture of censorship goes beyond complying with cybercrime laws; it often extends to providing regional countries with the technology to monitor and remove online web content themselves.

Cooperation with the architecture of censorship goes beyond complying with cybercrime laws; it often extends to providing regional countries with the technology to monitor and remove online web content themselves. Companies such as McAfee, Netsweeper, and Websense have been accused of selling technology to enable authorities to block online political, religious, historical, cultural, and other content deemed sensitive by Arab governments.

Consumers of such technology have included Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, the UAE, and Yemen. And it is not just western corporations that are turning a profit; Russian and Chinese companies have emerged as big players in the internet surveillance market, including in the Middle East.

Twitter Post

|

Changing the game plan: How to respond

Western-based international corporations' chief fault is not that they necessarily favour authoritarianism from an ideological standpoint, but that market imperatives and responsibilities toward shareholders lead to a certain political agnosticism that has advantaged authoritarian governments.

The good news is that it is possible to re-incentivise corporations to change their behaviour.

Governments, shareholders, and the general public have the means to help reframe corporations' perception of the bottom line.

In the United States, there are strategies to help. The Trump administration, in cooperation with Congress, has been considering tightening export controls on artificial intelligence and other products, with an eye to blunting China's efforts to achieve primacy in vital technology fields. Specific controls under US law should also be reviewed and strengthened in order to prevent large-scale tech transfers to regimes that may misuse certain technologies for internal repression; the extensive network of US strategic export controls furnishes many tools that can be used in this regard.

Stricter adherence to the Wassenaar Arrangement - essentially a voluntary pact - and other legal agreements to inhibit technology sales to (and by) repressive regimes would be useful and largely in keeping with bipartisan priorities established in both Democratic and Republican administrations.

|

Corporations also are not immune to pressure for change emanating from stockholders and the general public |  |

Arms transfers constitute another area that deserves fuller scrutiny, especially from Congress. Legislators are now considering tighter controls on arms sales to Saudi Arabia due to its role in the Yemen war. This is a welcome development. But broader legal restrictions remain on the books prohibiting arm sales to military units that abuse human rights. Enforcing the Leahy Law, for instance, would go a long way to put repressive regimes in the Arab world, and their US corporate suppliers, on notice that concern for human rights will remain a key consideration in licensing decisions.

Improving corporate governance, a growing concern of investors, implicitly encourages the maintenance of a good business reputation, which can be leveraged to take into account human rights concerns in international business dealings.

Twitter Post

|

Corporations also are not immune to pressure for change emanating from stockholders and the general public. For example, "ethical investing" is a significant phenomenon with a real bottom-line effect; according to The Wall Street Journal, over the past three years $20 billion flowed into so-called sustainable equity funds in the United States, which invest with a social, political, or environmental purpose in mind - an evident reaction to the 2016 presidential election and its runup.

This represents a 25 percent increase from 2014, and inflows in this category significantly outstrip those into traditional mutual funds. Saudi Arabia has been affected by growing pressures to divest from its stock market due to concerns about its behaviour, with foreign investors dumping a little more than $1 billion in Saudi stocks in one week of October - among the biggest selloffs since the kingdom admitted foreign investors in 2015.

Improving corporate governance, a growing concern of investors, implicitly encourages the maintenance of a good business reputation, which can be leveraged to take into account human rights concerns in international business dealings.

The private sector has not always acted as a good global citizen. There are certainly many examples where it has not. But corporations are not, in the end, entirely unaccountable. By means of a variety of actions - whether driven by governments, investors, or public opinion - the private sector can be encouraged to do more to support free societies and free peoples.

Charles W. Dunne is a non-resident fellow at Arab Center Washington DC.

Follow him on twitter: @charleswdunne

This article was reprinted with permission, from the Arab Center Washington DC.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News