How Sabra, Marvel’s ‘Captain Apartheid’, reveals Zionism’s kryptonite

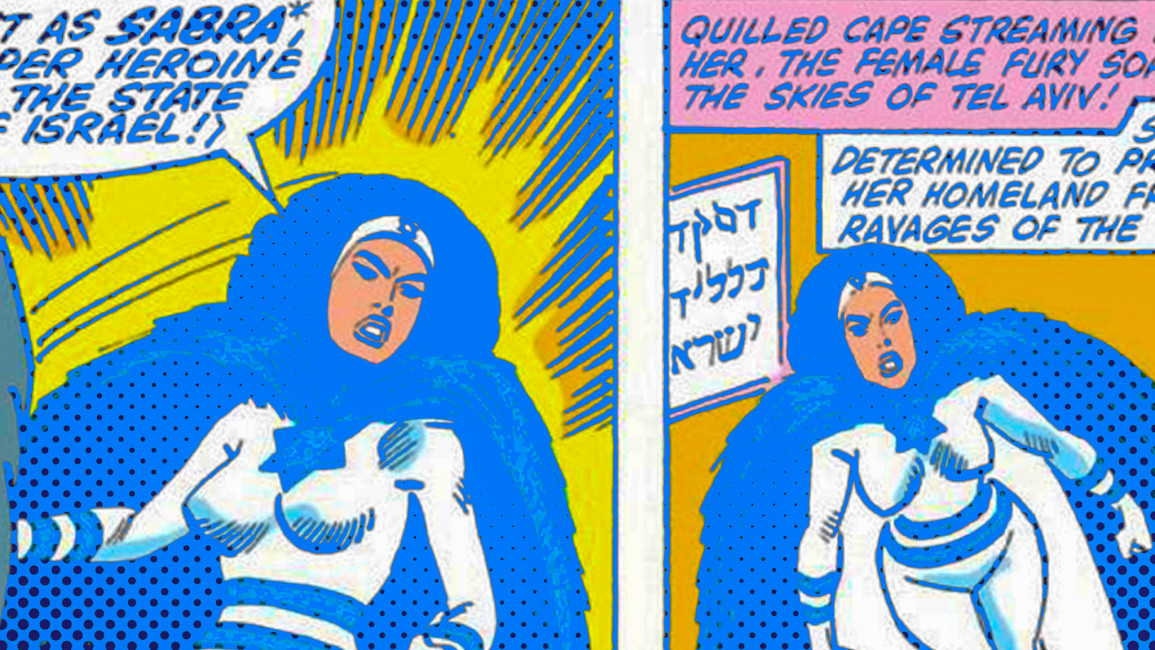

On 10 September during Disney’s D23 Expo, Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige announced the upcoming fourth Captain America film, Captain America: New World Order, and noted that among the side characters, will be a deep cut Z-list Israeli superhero from the Marvel decades-old library of comics lore called Sabra.

The character will be portrayed by Shira Haas, an Israeli actress known for her role in Unorthodox, a critically-acclaimed Netflix series about a Hasidic Jewish woman fleeing an arranged marriage in Brooklyn to start a new life in Berlin and shedding her Hasidic upbringing.

We presently don’t know what the plot will be, nevertheless almost immediately the announcement of Sabra in Captain America 4 elicited passionate reactions.

Many pro-Palestinian social media users and organisations spotlighted the character’s racist, orientalist origins and a petition has been launched to “let Marvel Studios know that whitewashing Israeli apartheid is not okay.”

We are outraged that @Marvel will glorify apartheid Israel's murder and ethnic cleansing of Indigenous Palestinians with its Israeli agent character in the next Captain America film.

— PACBI (@PACBI) September 12, 2022

The original comic’s ugly racism and valorization of Mossad are sickening.

We cannot be silent. pic.twitter.com/j4Ss2TBwDI

For their part, hardcore Zionists delighted in the announcement of Sabra’s inclusion in the next Captain America film, likely hoping the character on a popular public platform may beautify Israel’s rapidly decaying perception.

Among the orchestra of hot takes, one Israeli wasn’t so pleased; Uri Fink, a comic book creator, who claims that Sabra is a rip-off of his 1978 creation, Sabraman. While acknowledging that it was a great career opportunity for the Israeli actress Haas, Fink cautioned:

“Those who work at Marvel today are all sorts of progressives. I have nothing against them, but we won’t get the most accurate depiction of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

Why does this debate matter? It’s only fiction, after all, and that of a fiction, some may argue, of the era’s lowest sort - the US superhero genre, right?

Frankly, as silly and contrived as the plots and costumes may be, all of it does matter.

In the conclusion of his 1994 essay, Arab Images in American Comic Books, which analysed depictions of Arabs in comics from the early 1950s until the early 1990s, the late great academic Jack G. Shaheen noted:

“Comic book portraits do not exist in a vacuum. Each week, comics are read by more than 150 million impressionable children and young adults, many of whom identify with the superheroes and heroines. In today’s super $275 million industry, the average comic book reader is 21 years old and spends approximately $10 a week on comics. Those in the industry are perhaps more aware of the power of their creations to impress than anyone else.”

Today, the industry’s scale is astronomical in comparison. Disney’s Marvel Studios reportedly made more than $18 billion at the box office, not including profits from merchandising, Disney+, and more.

The eyes, hence psyches, are billions upon billions, and fiction and reality have a habit of blurring or supplanting each other.

As Israel’s incremental genocide on the Palestinians persists, and not long after Arabs and Muslims celebrated their respective superhero representation in the MCU, and six days before the fortieth anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, Marvel Studio’s decision to bring out Sabra at this very time should strike a note that Disney isn’t driven by ethnical sensitivities about justice, and is more interested in financially lucrative product expansion through the embracing of diversity underpinned by conservative and hegemonic messages.

But as creatures of profit, that means the decision-makers of Disney are swayed by their pockets; hit them where it hurts.

At the same time, Sabra can be a two-edged sword because as much as she is a tool to lionise Zionism, she unintentionally also reveals its limitations.

''Israeli characters were and are often depicted as strong, desirable women, capable and fierce fighters, yet they somehow need to be saved by Western male protagonists, against barbaric, brutish Arab male villains. Israel is strong, but needs your (the West) help.''

Sabra, as a superhero who serves the Israeli security agency Mossad, is unavoidably troubling.

Created in 1980 by writer Bill Mantlo and artist Sal Buscema for Marvel Comics - notably both white men, neither are Jewish, mirroring the hands behind Israel’s creation in 1948 – Sabra’s first full-fledged appearance was in Incredible Hulk vol. 1 #256 in a notoriously offensive story called “Power and Peril in the Promised Land”. (One wonders, will Disney reinterpret this story with the MCU’s Hulk, Mark Ruffalo, who hasn’t shied away from speaking out on Palestine?)

Sabra’s name stems from two sources: first, a Hebrew word, appropriated from Arabic, for the prickly pear (a fruit neither native nor exclusive to the land, which was actually brought in by Arab traders from Spain); and secondly, the modern Hebrew slang for ‘a native of Israel’.

Two years from her comic debut, the character’s name will also be inescapably tied with Israel’s bloody behaviour in the real world as a colonial xenophobic state with the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Beirut in 1982.

Sabra’s powers are mainly unoriginal, since the intention of her creation is less passion project and more of a propaganda exercise, and includes strength, speed, agility, reflexes, endurance and stamina, as well as limited invulnerability, but the twist in her abilities is that she can transfer her life source to another person, which allows them to gain a random power for a limited amount of time.

Her gender is also a common trope in US pop culture, especially after 1967. Israeli characters were and are often depicted as strong, desirable women, capable and fierce fighters, yet they somehow need to be saved by Western male protagonists, against barbaric, brutish Arab male villains. Israel is strong, but needs your (the West) help.

Much of her subsequent sporadic appearances since 1980 fall into the cliché norm propagating reductionist pro-Zionist sloganeering, Arab-bashing, sanctioning the Israeli governments’ violence and furthering the entanglement of a vibrant religion, Judaism, with a xenophobic political ideology, Zionism.

But while Sabra is a superhero embodiment of the state of Israel, she is also a mutant.

Zionism - the very argument for Israel’s existence - assumes the idea that Jewishness is a concrete and unique identity separate from the rest of humanity. Assimilation with ‘the other’ an impossibility due to the stubbornly lingering presence of anti-Semitism, the Jewish community must thus gather together in one territory, which a series of circumstances has settled on would be historical Palestine (while reason and natives of the lands be damned).

And here according to current Marvel comic lore, the mutants of earth are rallying around an ideology that cooperation with humanity is futile and solution to Homo sapient discrimination against the Homo superior is to gather together in Krakoa, a safe sentient island nation for them.

The implication of this larger narrative thread in the world of Marvel is clear, Sabra cannot have allegiance to the Israeli state and be a supporter of mutant rights simultaneously, and there lies a (preordained?) tension within this flimsy tool of crude propaganda.

Ultimately revealing Zionism's inherently fragile character, to an extent that even when faced with fictional conundrums, it falls apart quite quickly.

Yazan Al-Saadi is the International Editor for The New Arab. He is an analyst, writer, editor, and researcher with over 10 years of experience in social research alongside communications and reporting.

Join the conversation: @The_NewArab

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News