The Balfour Declaration: The fate of Palestinians was decided with the stroke of a pen

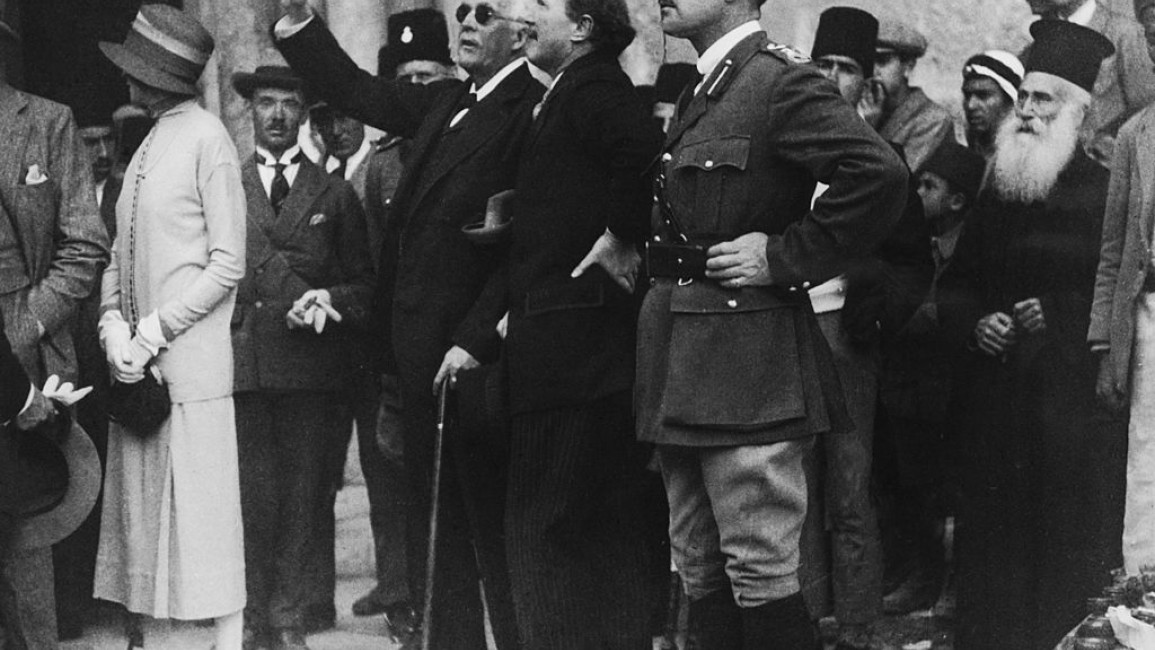

This week marks the 105th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, a pledge by British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour on behalf of Britain’s cabinet, to grant the Zionist Movement a homeland in Palestine. In only a few words, it combined colonial planning, wartime propaganda, Biblical references, and clear sympathy with the Zionist enterprise.

At that fateful moment of November 1917, Britain became the patron of Theodor Herzl’s vision of Jewish statehood and sovereignty. The British authorities thereafter facilitated the conditions for the establishment of a Jewish national home, at a time when Jews constituted only 6% of Palestine’s population.

With the British government greasing the wheel for European Jewish immigration into the country, albeit at times restricting it in fear of Palestinian protests, the Jewish population grew significantly. From 11% of Palestine’s population with the official commencement of the British Mandate in September 1923, to nearly 27% in 1935, and climbing to 32% in 1947. With Israel’s inception in 1948, nearly 750,000 Palestinians were driven out of their homes, making Jews the majority at 82% of the population.

''105 years later, the impact of the Balfour Declaration remains deeply entrenched in the daily lives of Palestinians. The current statelessness, diaspora, military occupation, and apartheid, as well as the siege and multiple wars on Gaza and several intifadas across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, are but an accumulative and inevitable consequence of Arthur Balfour’s ominous words.''

The Balfour Declaration never mentioned the Palestinian Arab majority by name, it only acknowledged their existence as merely “the non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” whose civil and religious rights - not national or political - "may not be prejudiced.”

Britain’s disregard for the native population may have been helped by the Palestinian late response to the declaration, for reasons related to society’s shattered media outlets and political unclarity following the 1917 Ottoman defeat and the British invasion of Palestine. Later attempts by Palestine’s political and intellectual elites to challenge Britain’s step - in London, the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, and the newly established League of Nations - were met with almost the same level of condescending disregard as in the declaration’s sixty-seven words.

Palestinians’ most notable but ultimately fruitless endeavour to confront the Balfour plan was a series of seven congresses organised by a country-wide network of Muslim and Christian societies between 1919 and 1928. In contrast to these elite-led initiatives, explains historian Rashid Khalidi, popular dissatisfaction with British support for Zionism manifested as demonstrations, strikes, and riots, with violence flaring notably in 1920, 1921, 1929, and 1936. All the uprisings were met with oppressive measures by the British mandate authorities.

In the words of Edward Said, the Balfour Declaration was “made by a European power, about a non-European territory, in a flat disregard of both the presence and wishes of the native majority resident in that territory.” Standing against such enormous odds and systematically weakened, it was inevitable that Palestinians would see a Jewish state established on their land and European Jews move into their homes, whilst being ethnically cleansed, displaced, and dispossessed.

105 years later, the impact of the Balfour Declaration remains deeply entrenched in the daily lives of Palestinians. The current statelessness, diaspora, military occupation, and apartheid, as well as the siege and multiple wars on Gaza and several intifadas across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, are but an accumulative and inevitable consequence of Arthur Balfour’s ominous words.

The British Empire, with a stroke of a pen, wrote off not only the national and political aspirations of Palestine’s native majority, but also their very existence. And today, the consecutive British governments have continued this legacy by supporting Israel and refusing to recognise a Palestinian state, let alone offer Palestinians an apology.

Despite the lip service to the two-state solution, Britain’s historical sin is further substantiated by tightening the grip on pro-Palestine activism in the United Kingdom, not least labelling it as anti-Semitism. It is the same label that the Zionist Movement used as a moral ground to justify a Jewish state in Palestine.

Dr Emad Moussa is a researcher and writer who specialises in the politics and political psychology of Palestine/Israel.

Follow him on Twitter: @emadmoussa

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News