Anti-coronavirus measures spark fears of rights rollback across the Middle East

As the world battles the COVID-19 pandemic, more than three billion people are now living under lockdown and, in some cases, strict surveillance.

While there is widespread acceptance that robust measures are needed to slow the infection rate, critics have voiced fears that authoritarian states will overreach and, once the public health threat has passed, keep some of the tough new emergency measures in their toolkits.

This concern is amplified in the Middle East and North Africa, with poorly ranked human rights records, a cast of authoritarian regimes able to bulk up security apparatuses largely unopposed and many states already reeling from political turmoil and economic hardship.

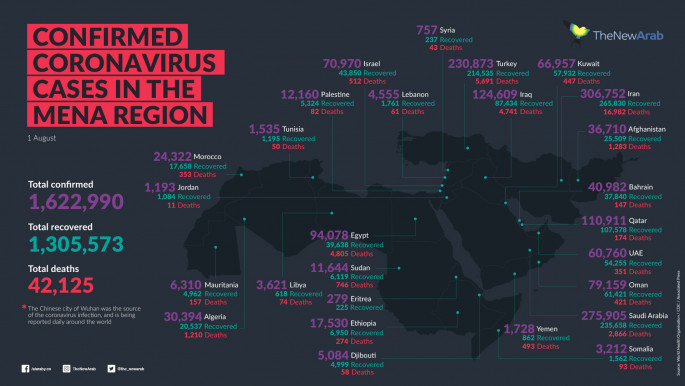

The region had as of Saturday recorded 2,291 COVID-19 deaths out of 35,618 confirmed cases, according to figures collated from states and the World Health Organisation, which has urged "concrete action" from governments to contain the virus.

Authorities have curtailed movement, clamped down on gatherings and arrested those who disobey the confinement orders.

The sight of military vehicles patrolling otherwise empty roads to enforce curfews or lockdowns in countries such as Morocco and Jordan stands in stark contrast to mass protests which last year brought down leaders in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Sudan.

In Jordan, where King Abdallah II signed a decree giving the government exceptional powers, hundreds of people have been arrested for breaking a curfew.

While the government said the powers would be used to the "narrowest extent", Human Rights Watch (HRW) urged Amman not to abuse fundamental rights for the cause of combatting the virus.

In Morocco, known for its muscular security policy, the arrests of offenders - who risk heavy fines and jail time - have generated little protest and are even praised on social media.

Like many countries, Rabat has bolstered a campaign against misinformation, but the adoption without debate of a law on social media controls has elicited concern.

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

'Accelerate the repression'

Many are crying foul over surveillance in Israel, where domestic security agency Shin Bet, usually focused on "anti-terrorist activities", is now authorised to collect data on citizens as part of the fight against COVID-19.

Embattled Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu drew criticism for imposing the measure with an emergency decree as a parliamentary committee didn't have enough time to rule on it.

In Algeria, more than a year into an unprecedented popular movement known as "Hirak", it took the emergence of the pandemic to pause weekly protests.

But rights groups have accused Algerian authorities of using the health crisis to crack down on dissent via the courts.

|

|

"The Hirak has suspended its marches but the #Algeria government has not suspended its repression," HRW's Eric Goldstein wrote on Twitter after journalist Khaled Drareni, who had been arrested several times for covering the protests, was put in pre-trial detention on Thursday.

Lebanon faced similar accusations as police on Friday night dismantled tents in the heart of the capital Beirut where protesters had maintained a sit-in to keep up pressure on authorities.

The authorities "are taking advantage of the fact that people are preoccupied with their health and confined to repress any dissenting voices", activist and film director Lucien Bourjeily tweeted.

In the fledgling democracy of Tunisia - a former police state where security apparatuses have seen little reform - many have denounced heavy-handed police enforcement of pandemic-related movement restrictions.

The Tunisian League for Human Rights has requested clarifications on social distancing measures after people expressed frustration online over apparently arbitrary police interventions.

Prisoners of conscience

In Egypt, authorities have targeted media questioning low official virus infection figures.

British newspaper The Guardian said its correspondent was forced out of the country over an article reporting a study that suggested authorities were underreporting cases.

With the number of cases rising, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's government imposed movement restrictions and threatened heavy fines and prison sentences for non-compliance.

In a country lacking an independent media or judiciary, families of prisoners of conscience sounded the alarm over the possibility of a coronavirus outbreak in overcrowded and unsanitary prisons.

Amnesty International has called for the "immediate and unconditional" release of political prisoners, estimated by rights groups to number around 60,000, only 15 of which have so far been let out by Egyptian authorities.

Jordan, Tunisia, Iran and Sudan have ordered thousands of inmates to be freed to limit the risk of contagion.

Activists in the Gulf too have called for the release of political prisoners held in what HRW researcher Hiba Zayadin said are often overcrowded and unsanitary conditions with limited access to health care.

Kuwaiti activist Anwar al-Rasheed asked on Twitter, "In the midst of this pandemic, is it not yet the time to release prisoners of conscience?"

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to stay connected