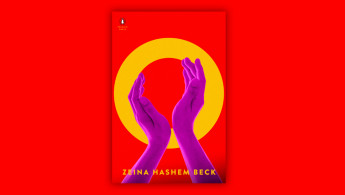

Zeina Hashem Beck's poetry collection 'O': A warming serenade to the cyclical

O, as a letter, a shape, or a geometric model, is found at the start of hymns and at the centre of our bodies. In cultural and spiritual beliefs and practices, it symbolises life’s cyclicality; stories that are retold and lessons revised, themes of reincarnation and revival. It is often O’s wholeness which suggests the possibility of divine perfection in our universe.

For Zeina Hashem Beck, O is the title of her latest collection of poems exploring these simultaneously sacred and worldly themes through triptychs, odes and blank spaces.

“[O] was a turn inwards. I decided that I was going to do the emotional and the sentimental. Unlike my previous work, there would be more pause and silence – looking at the body as a city and what it carries within it.”

"Writers have obsessions that often come up, even when they don’t realise it. In O, mine were mother, God, body, joy, ode, love, home. It was important to me that O wouldn’t be reduced to my experience of trauma"

On a Zoom call in early May, Zeina curses a newly cut bang, pushing it away from her face and gesticulating her hands as she introduces herself. From the beginning, there is inexplicable ease that emphatically welcomes the listener into her presence. She digresses her answers, weaving memories and jokes into the conversation, using words like stroubia and orale, relics from a childhood in Tripoli, and promptly apologising for the chatter.

“Since I was a child, I wanted to make things – build things with my hands. At some stage, I discovered you could create something with language, and that it could connect you with another person who would also feel transported by this particular power that only a poem can have. I’m drawn to how we can use language to spellbind us within that minimal space.”

During the conversation, she jumps excitingly between the distinct places that contoured her vision of O: the polluted sea and inedible fish, a kitchen balcony wafting in the smell of gardenias, an airless delivery room, her formative years at the American University of Beirut. There is a crescendo for release that is visceral in her speech and in each poem, which has been carefully selected by Zeina herself after going back and forth with her editor about their chronological and intentional order.

“Writers have obsessions that often come up, even when they don’t realise it. In O, mine were mother, God, body, joy, ode, love, home. It was important to me that O wouldn’t be reduced to my experience of trauma.”

We joke about initial impressions of the title, an allusion to the Big O immediately coming to mind, which contrasts with the violation and rage, forgiveness and acceptance that underlie her odes to revolutions, antidepressants, and friendship. In O, Zeina pulses the nervous system with an electric shock to the heart. She departs from the nostalgic and surpasses the polite and gentle for the truth.

In Say It, an experimental poem in the style of a fill-in-the-blank riddle, she asks the reader to use their own words to deliver a shared experience of assault, betrayal, and a loud silence that haunts the soul and consumes the body – "& years later you couldn’t kiss your boyfriend without ___, no matter how tender his eyes."

“[Say It] was difficult, I didn’t want to write it, and then I didn’t want to include it in O I worried it would be too heavy, [that] it would sink the book. So I asked a close friend to read it, and she said ‘yes, it’s heavy, but it’s fine.’”

"Despite O’s episodes of disappointment and anger, hurt and hunger, Zeina finds herself back in prayer; thankful for the sun and her hips, for her friendships and her antidepressants, she basks in this new light after having stretched herself out for the tide to come through"

In Zeina’s world, women speak of flinging their bodies out of balconies. Her unabashed and unapologetic performance of womanhood sets the scene. Rejecting the way things are and searching for more are both motifs that recur throughout her verses and are felt in the line breaks and pauses.

"Is God the boss, mom?" her daughter asks in Things My Daughter Said, to which Zeina responds in Poem Beginning and Ending with My Birth.

She recalls a reluctant nurse that dismissed her wishes for an epidural, "stab my spine painless or I’ll dig my claws into your jugular […] don’t you applaud the sacrifice of mothers, don’t you God them."

“What they don’t tell you about birth is how gory it is. But in this blood, in this gore, there is God [...] This doesn’t mean I’m deifying mothers. I wanted to depict mothers as these flawed human beings who can absolutely fuck up, and in this, there’s much more kindness than putting them on a pedestal.”

Zeina speaks of Beirut as a leash that “suffocates [her] the further [she] strays,” a timely homage to summer’s returning expatriates who must soon rinse the taste of their country out of their mouths before returning to their livelihoods abroad.

When asked who it is that she writes for, Zeina is quick to respond that in the moment of writing the poem, she’s not thinking of the audience.

However, her subtle nods to the displaced and her appreciation of their unending search for a home in foreign lands suggest otherwise.

In Everything Here Is an Absolute, Zeina boldly compares New York’s East Houston Street to Beirut, turning to a stranger, expecting agreement only to dwell in his polite silence. There are no fire escapes here / but there could have been.

|

What the reader viscerally feels throughout O is the arduous refurbishing of Zeina’s interiority, shifting joy and sadness into coherent structures that bring to life a woman whose community sustains her through heartbreak and goodbyes, exploring her peace and her pain in both English and Arabic.

“[My] poetry isn’t going to free Palestine, it’s not going to help Lebanon. Sometimes we romanticise poetry, telling others that it’ll save the world – it won’t. We need those revolutions and movements, but what [poetry] can do is save us. I know it saved me – the existential angst I inherited, then why the fuck are we here? […] it gave me language as a tool to channel all of it into making something almost magical.”

And there is indeed magic that underlies O in its vivid description of tiny bones chewed on by human teeth and revolutions that settle on a city like a sheet of dust. There is also companionship and self-perseverance that binds these disparate moments together.

“Yes, there’s my partner’s love, and yes, there are antidepressants, but nothing has sustained me like my girlfriends have […] the way they uphold me, the way that they push me, that connection in womanhood, in our rage, in our joy, and in our dance – everything.”

Despite O’s episodes of disappointment and anger, hurt and hunger, Zeina finds herself back in prayer; thankful for the sun and her hips, for her friendships and her antidepressants, she basks in this new light after having stretched herself out for the tide to come through.

"Little world little world," she triumphantly concludes, "I love you.

Zeina Hashem Beck’s collection, O, is out now from Penguin Books

Tracy Jeff Jawad is a political researcher and writer who has worked for the United Nations in New York City and the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut

![Zeina Hashem Beck [photo credit: Adonis Bdaywi]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_1_1/public/2022-07/Zeina%204%20%282%29_0.jpg?h=4718e473&itok=PACssXOO)