VR technology revives lost archaeological marvels from the Middle East

In today's world, heritage sites are vanishing faster than they can be recorded. In the Middle East, rampant wars and 'precision' airstrikes have disfigured ancient city skylines and decimated relics.

The year Bosnia's Mostar Bridge was destroyed in 1993 represented a watershed moment when the international community collectively vowed: 'never again'. Despite the promise to protect architectural riches, the fragmentary state of Middle Eastern heritage communicates the betrayal of that promise.

On 4 August 2020, Beirut had its day of reckoning. The country shook violently after a stockpile of ammonium nitrate exploded and tore through Beirut's urban fabric, killing over 180 civilians, including first responders. Prized heritage that had survived Lebanon's civil war was dealt another deadly blow.

In Iraq and Syria, the birth of the Islamic State cost ancient heritage dearly. In 2017, Mosul lost the Tomb of Jonah, and two years later its iconic hunchback minaret was reduced to a concrete stump. The same years witnessed the wholesale destruction of Yemen's Dhamar Museum, Syria's ancient Baalshamin temple in Palmyra and more.

One contingency plan that students, conservationists and architects from the region are rallying around is digital preservation. Without physical access to their heritage, a new generation of digital conservationists are utilising state-of-the-art virtual reality technology to revive withering structures and tell their stories.

|

Without physical access to their heritage, a new generation of digital conservationists are utilising state-of-the-art virtual reality technology to revive withering structures and tell their stories |  |

The New Arab caught up with Jordanian architect and multidisciplinary artist Nemeh Rihani, a doctoral student and researcher at Liverpool University's Centre for Architecture and the Visual Arts (CAVA).

Rihani has been documenting archaeological sites, both extinct and at-risk, using digital applications and games technologies. "It's unfortunate, but the reality is that no one can guarantee the longevity of these sites" Rihani told The New Arab. He recalled the bureaucratised and ineffective process of urban conservation he had witnessed while working on projects back in Jordan, and rued the loss of cultural property, wilfully destroyed by IS militants. Digital preservation offers a middle-of-the-road option.

|

|

| 3D Dense Point cloud model of Al-Khazneh in Petra |

Rihani's method relies solely on crowd-sourced images, that he joked allows artists to create 3D digital replicas of archaeological environments from the comfort of your own home. The methodology is particularly advantageous in times of Covid-19 and complies with the world's new social distancing etiquette. The technology Rihani used, he explains, is known as photogrammetry, "the science of making measurements from photographs".

Rihani's most successful digital prototype, Al Khazneh, is anchored in the ancient archaeological Nabatean city of Petra, in southern Jordan. It is Petra's most photographed monument; a Temple whose sand-stone carved, red-rose facade, greets visitors at the end of a narrow ravine along the main trail. By retracing the visitor's footsteps to the site, Rihani was able to archive shots captured from every angle when rebuilding a 3D model.

In contrast to Petra, the task of creating a 3D model of Syria's Temple of Bel was complicated by the dearth of publicly accessible images. Two full chambers were all Rihani could digitally archive, "but a full capture of the site was not possible" Rihani explained.

|

In the Middle East, rampant wars and 'precision' airstrikes have disfigured ancient city skylines and decimated relics |  |

"Visitors commonly photograph monuments from the front, back and side but less frequently from above". This, Rihani added, can result in an incomplete 3D rendering. He explained that one easy way around this is to use drone-captured footage, that is, if the site still exists, and once Covid-19 restrictions ease-up.

In the second phase of his research, Rihani will shift his focus to digital storytelling. He will apply augmented reality, like a play-back feature, animating and interpreting historic events that users can engage with. Rihani cites epic battles between the Nabateans and Romans, as one example, adding that someday he aspires to animate the story of how Petra came into being; how it was sculpted into mountain-faces, and carved out of the bedrock.

Two decades ago, Mike Gogan was inspired by similar virtual possibilities. Gogan founded The Virtual Experience Company (VEC) and has since been working on cultural protection programmes in the UK, Tunisia, and Oman, and in partnership with British institutions, and universities in the UK and Middle Eastern universities, and their student cohorts.

|

|

| Inside Ksar Said palace in Tunisia. [The Virtual Experience Company] |

"For many years, VR was a technology that was looking for an application," Gogan told The New Arab, "and while it's not quite there", technological means are making hitherto unseen worlds accessible, albeit digitally.

In Oman, the VEO teamed up with the Sultanate, creating digital copies of the Bahla Fort as it existed in the Bronze, early and late Iron Ages.

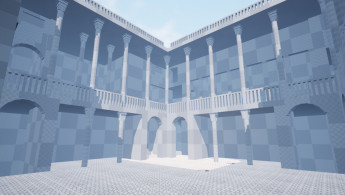

In Tunisia, Gogan joined forces alongside Tunisia's National Heritage Institute, Rambourg Foundation, British Foundation, and Cambridge University, creating a virtual-replica of Ksar Said Palace that students and members of the public can navigate, ex-situ.

|

The 3D models are an act of recovery, reviving both lost memories and access to a site |  |

"Everything that was absorbed into Tunisian culture is there; Islamic, Ottoman, French, and Italian influences," Gogan said, underlining the site's local and historical significance. Educational resources were also created, to help teachers engage children in local history, aided by digital tools.

Each project involves a diverse coalition of participants, an ever-growing pool of expertise or, as Gogan describes, "some of the biggest universities and game developers in the world, working alongside some of the smallest schools in the world."

On a past visit to the archaeological site of Sbeitla in Tunisia, Gogan stood before "hectares and hectares of Roman city," completely alone. "I was approached by a man," he recalled, "he spoke no English, and I don't speak any Arabic. German turned out to be the common language."

|

|

| 3D Photogrammetric reconstruction of the Temple of Bel, Palmyra |

The man was a local tour guide, who accompanied Gogan around Sbeitla, narrating it's multicultural historical past and revealing corresponding Islamic, Roman and Byzantium motifs. Nearby in the mountains, the guide pointed to a terrorist hideout, explaining to Gogan that it was why visitors were nowhere to be seen.

Though typically undervalued, tour guides provide vital access to local history, stories, and other details known only to locals. "We bring the digital tools, but the heritage is Tunisian, and all the guidance is Tunisian," Gogan stressed.

Irish-Iraqi visual artist and photographer, Basil al-Rawi, is a doctoral student at the Glasgow School of Art, reviving a symbol of Baghdad's lost past - the Shanasheel House. These houses are famed for their elaborate courtyard structure, intricate latticing and enchanting balconies.

|

A new generation of artists are working to breathe new (digital) life into lost and at-risk heritage sites |  |

Using graphic 3D rendering, al-Rawi is creating a digital replica of the traditional Baghdadi home, whose physical counterparts have severely deteriorated beneath years of war, neglect and corruption.

The model will be delivered for the final phase of al-Rawi's doctoral project, the Iraq Photo Archive. In the first phases of his project, members of the Iraqi diaspora curate their own archive by submitting personal photos of the life they left behind in their motherland. The second phase consists of interviews with people that feature in the submitted photos. Participants will eventually access these stories, in audio-visual format.

"I was thinking about a virtual space to house the memories and narratives that are relayed from the photos in the archive" al-Rawi explained. "A space that people can navigate and encounter objects, and narratives that begin conversations, as it would in real life".

|

|

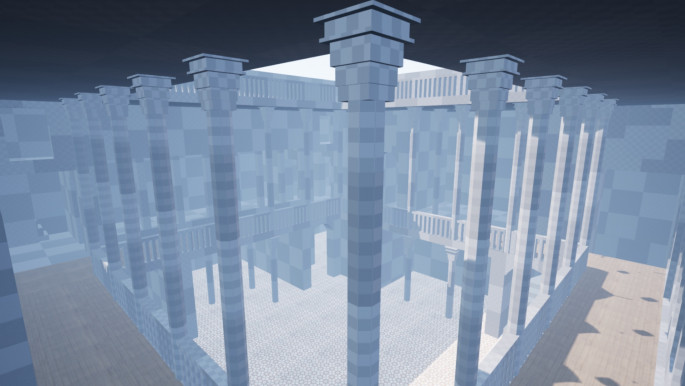

| First draft of al-Rawi's Shanasheel prototype |

Unable to travel to Iraq to encounter Shanasheel homes in the flesh, al-Rawi relies on the surviving texts and photos that document this potent symbol of life in Baghdad, once upon a time.

"I'm essentially taking a cast from all of these references to create a virtually navigable sculpture" he said, citing paintings by Lorna Selim and architectural texts by Iraqi architect Ihsan Fethi as seminal. "One of the challenges I face is that I am not a trained architect so interpreting 2D plans and the photographic references takes some trial and error and experimentation."

Nearer to its completion, al-Rawi will share the end results with Iraqi participants who will be invited to share feedback on "the authenticity of the spaces represented."

The process is explorative as much as it is generative. Al-Rawi's 3D model stands out as an act of recovery, reviving both lost memories and access to a site that continues to symbolise happier times, and the position and wealth ordinary civilians once held. Al-Rawi explained that the project has also allowed him to explore his personal identity "through spaces and places" he had never been, and through direct engagement with members of the Iraqi community.

Al-Rawi, like Nimeh and Gogan, represent the newest crop of artists working doggedly to breathe new (digital) life into lost and at-risk heritage, and in doing so, reviving a digital library of artefacts and sites, and the stories that envelop them.

Follow her on Twitter: @NazliTarzi

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News