Revisiting Clarno's 'Neoliberal Apartheid': South Africa, Palestine, and the dangers of Western peace-making

News of the US House of Representatives rejecting a $17.6 billion aid package to Israel suggests that, for the first time, we are seeing political winds changing in the favour of Palestine and the Palestinians.

Western politicians have largely been publicly supportive of Israel’s ‘right to self-defence’ and maintained a consistent line in this regard – their refusal to call for a ceasefire is absurdly based on the notion that somehow the fighting will continue by Hamas.

Still, the extent of the devastation has reached the point where public officials are being forced to backtrack – seemingly due to the strength of public opinion.

On 30 January 2024, the UK Foreign Secretary David Cameron announced that the UK is willing to recognise a two-state solution. On the same day, amid news that the UK opposition Labour party was losing Muslim votes over the party leader Keir Starmer’s support for war crimes by the Israeli regime, Labour MP Wes Streeting went on LBC radio to declare that they would work with the Palestinian Authority to push for a Palestinian state – one that was an inalienable right.

"Understanding the economics of the PA is not possible without centring the role of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the US government – all of whom have been integral to the formation of a private-sector-led, free-market approach to a nascent Palestinian state"

Ostensibly, these public pronouncements from both sides of Parliament indicate that there has been a shift in British foreign policy-making, even as both the US and the UK announced their withdrawal of funding for UNRWA, but it bears the hallmarks of control, rather than support for the rights of Palestinians to control their future.

This controlled peace has been a consistent practice of Western nations in the process of decolonisation – that rather than lose control of a situation, they would rather present themselves as reconciled peacemakers in the world.

Recent protests to heckle the Palestinian ambassador to the UK, Husam Zomlot speak to the degree of discontent there resides in pro-Palestine groups – and the extent to which the Palestinian Authority (PA) represents the control that Western nations are desperately seeking to hold. The PA has played a role since Oslo and suggests its status as the authority over the Palestinian people is more of a gatekeeper for its own elite interests.

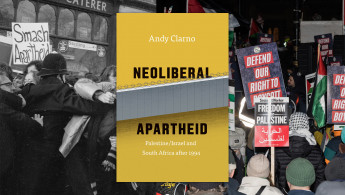

With that context in mind, it is important to centre the important book Neoliberal Apartheid: Palestine/Israel and South Africa after 1994 by Andy Clarno – a book that seeks to reimagine how we think of the post-Apartheid era in South Africa in relation to the continued apartheid across the occupied Palestinian territories.

Central to Clarno’s thesis is the idea that just as South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world, our imagining of a post-apartheid future for Palestine cannot simply be reduced to the acceptance of a new political state – but rather as a just future that is not trapped in a cycle of neoliberal debt and inequality.

|

Clarno’s 2017 book sets out the neoliberal project in Israel as beginning in 1985, with a free trade agreement with the US known as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Plan – a way for Israel to liberalise trade and investment into the country, but at the same time open doors to support for the US.

This paved the way for intensified suppression of the Palestinian people, culminating two years later in the First Intifada in 1987. Over the six years of Palestinian resistance, Israel’s economic needs drove the Oslo negotiation process, as Shimon Peres attempted to open Israel up to the economies of the world – signing free trade agreements with Egypt and Jordan (p.39). It was also the moment that the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) opted to find a pathway to peace (p.31).

Palestine and South Africa: A new form of 'neoliberal apartheid'

As with the negotiations by Western powers, the white supremacist government of South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC), the guarantee of an autonomous political future became predicated on major concessions to a structure of international finance and capitalist elites within the country – in particular – the guarantee by the ANC that there would be no nationalisation of mines and land that had been appropriated through violent colonisation.

Instead, South Africa’s political gains meant it was tied now to a neoliberal economic order – one that privileged free trade above all else (p.32). The Oslo process, the negotiations with the PLO and the eventual formation of the PA, meant that the Intifada, with all of its grievances at the state of dispossession within Palestine, was also bound to follow a similar trajectory as post-apartheid South Africa – one where structural inequalities would become pervasive in the name of security and control. As Andy Clarno writes:

‘"The formation of the Palestinian Authority allowed Israel to partially outsource the occupation. From its inception, the economic policies of the PA have been based on the neoliberal vision of a private-sector-led, export-oriented, free-market-economy.

During the 1990s, however, the PA introduced a public employment program to help absorb surplus workers and contain frustration with Oslo. The schools, hospitals, and pensions operated by the PA are funded primarily by grants and loans from "donor states” in Europe, North America, and the Arab Gulf and from taxes collected by Israel on imported goods consumed by Palestinians in the occupied territories.

Israel and the donor states exploit this dependency to shape the policies of the PA, refusing to release the funds unless the PA meets their demands."(p.40)

The Palestinian Authority as 'security' for Israel

Understanding the economics of the PA is not possible without centring the role of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the US government – all of whom have been integral to the formation of a private-sector-led, free-market approach to a nascent Palestinian state.

Clarno cites Adel Samara in noting, “the PA’s economy may be alone in having been designed from its very beginning by the policies and prescriptions of globalizing institutions.” (p.97)

In May 2008, the Palestine Investment Conference (PIC) was organised in Bethlehem by PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, as a means of opening opportunities for Palestinian businessmen and elites to open up the occupied Palestinian territory markets to investors in the US and EU. For these investors to come, there was a great deal of coordination between Israel and the PA.

The former ensured that delegates were able to pass unimpeded through borders and checkpoints, while the PA took on the dirty work of arresting activists across localities to prevent any form of demonstration (p.101). This led to a new situation for PA elites:

"Visitors to Ramallah are often struck by the lavish lifestyle of the Palestinian elite: fancy restaurants, expensive cars, five-star hotels, and private “villas.”

Billboards in Ramallah advertise real estate opportunities, resorts, luxury cars, hotels, private swimming pools, and multinational restaurant chains.

Most residents of Ramallah, however, are poor and working-class Palestinians who critique the consumption and complicity of the elites. Like other Palestinian enclaves, Ramallah is a site of concentrated inequality." (p.51)

It is those within the PA, or those closely associated with the leadership of the PA that have benefited from this privileged status. The PA’s role is thus not only to maintain ‘security’ for Israel but also as a form of containment to maintain a status quo that they are largely privileged to hold – a concentrated inequality.

Funnelled through reforms by Prime Minister of the PA, Salam Fayyad (a former IMF employee), the restructuring of the Palestinian economy to serve an elite cadre wasn’t an accident as much as it was by design through the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP) – which of course took place in coordination with the British Department for International Development and the World Bank (p.101). Palestine might have been open for business, but really only to serve a Palestinian elite, Israel’s security need, and a globalist elite.

The PA as a security force, is steeped in the practices of colonisation and empire as coordination and training takes place with the US, EU, UK, and Canada, alongside the intelligence and military regimes of neighbouring Middle Eastern countries.

The PA thus takes on the mantle of colonial control in the way it suppresses the degree of disenfranchisement among poorer Palestinians, but ultimately as a means of maintaining its own limited status:

"Much like their attraction to neoliberalism, PA officials embrace security coordination as a pathway to statehood. Yet they confront a fundamentally different vision from Israeli officials, who view security coordination as a foundation for sustainable colonization.

Rather than achieving a monopoly of violence, therefore, the PA remains a proxy force with limited authority inside the West Bank enclosures. Security coordination has allowed the PA/Fatah to assert supremacy over other Palestinian factions within these enclosures.

While operating through a discursive focus of “Palestinian/Arab/Muslim terrorism,” however, PA and Israeli security forces have carried out an authoritarian crackdown against Palestinian critics of the Israeli occupation, Fatah rule, and the Oslo process. Gaza provides an important foil for the West Bank, an image of what might happen if Israel and the PA fail in their joint effort to enforce stability." (p.192)

The protests against Mahmoud Abbas taking place in the West Bank only point to the fragility of the PA’s positioning as a security enforcer in the region.

They have positioned themselves as the only partner that foreign governments are willing to engage, particularly since Mahmoud Abbas took control of the PA in January 2005 – immediately declaring an end to the Second Intifada and working with US General William Ward to restructure the PA’s security forces.

One year later, Hamas won the election, and rather than accept they had lost their mandate, the US engineered an attempted coup by training a newly revitalised PA into the Gaza Strip to remove Hamas from power – a plan that ultimately failed – causing the political rift between the West Bank and Gaza (p.158).

The opening of markets in the context of South Africa and Palestine has been presented as the best pathway for long-term peace – one that is capable of bringing prosperity to all. Except, the reality of both geographies, has been the continuity of settler-colonial oppression. In the case of South Africa, this takes place primarily through the economy and securitisation of black lives – while in Palestine these continuities are all-pervasive.

In both cases, the existence of a well-to-do elite masks the extent of the inequalities that continue to grow. For the vast majority of Palestinians, if they are not part of the privileged bourgeoise, their options in life lie between the ‘choice’ of working on building Israeli settlements on lands that have been unlawfully confiscated, or working as part of the PA security forces that suppress Palestinians resistance (p.41) – a choice that is between the devil and the deep blue sea.

As calls from inside the UK intensify to formally recognise a Palestinian state – any such call should be met with a great deal of circumspection. They are already involved but as part of a process of pacification – not justice.

Dr Asim Qureshi is the Research Director of the advocacy group CAGE and has authored a number of books detailing the impact of the global War on Terror

Follow him on Twitter: @AsimCP

![On Tuesday 20 February, South Africa told the International Criminal Court that Israel is applying an even more extreme version of apartheid in the Palestinian territories than experienced in South Africa before 1994 [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2024-02/GettyImages-639793444.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=fswfgkzN)