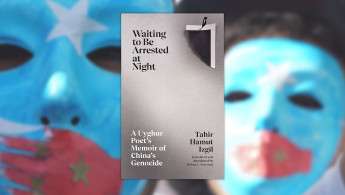

Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A nail-biting memoir of Uyghur genocide, escape, and freedom

I attempted to fall asleep by counting backwards from 100. If that didn't work, I planned to start again at 200 and then at 300. All the while, I was trying to listen for any sounds of footsteps or walkie-talkies crackling on the landing. I was preparing myself for the inevitable pounding at the door.

Should I open up or pretend not to be at home? I crouched at the end of my bed, fully dressed in case the entrance was breached.

Anticipating heavy footsteps up the stairs at any moment, I longed for rest until I somehow managed to drift off in the early hours. Waking up, I felt relieved that one more night had passed without any incident.

I knew as an expat living in the Uyghur region in 2017, at the height of the roundups and mass arrests of Uyghurs and Turkic peoples of North West China, my fate would be nothing worse than being thrown out onto the wintry streets or interrogation and then released. As far as I was concerned, the worst-case scenario was being kicked out of a country that had become my second home.

"The story of Izgil's eventual escape is a nail-biting but understated page-turner that delves deeply into the dystopian madness that characterises Uyghur life"

For Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil, who managed to fly under the radar until April 2017, lying awake at night took on more sinister significance.

His friends and neighbours, many of whom were writers and poets like him, were vanishing rapidly, leaving him feeling helpless and uncertain about his own fate.

Understanding China's crackdown on the Uyghur way of life

Izgil's memoir, Waiting to be Arrested at Night, published towards the end of 2023 and written from the eventual safety of American shores, takes the reader deep into the Orwellian world of 21st-century surveillance state Xinjiang, described later by the U.S. State Department in 2021 as an "open-air prison," where the Uyghur people and other Turkic groups were pursued relentlessly for the style of their clothes, the length of their beard or the names of their children.

A horror was unfolding that would see more than one million, mostly Uyghurs, herded extra-judicially into internment camps, euphemistically known as vocational training camps, for 're-education'.

Nights like this became the norm after the intensive crackdown in 2016 by the new incumbent regional head, Chen Quanguo. The crackdown would later described as the largest mass incarceration of a people group since the Jewish Holocaust.

Following orders from President Xi Jinping himself — clamping down on Uyghurs under the guise of prosecuting his own 'War on Terror' — daylight hours became a continuous round of checkpoints, airport-style security, and stop and search, while dodging relentless mobile phone scrutiny and ID card checks.

Swathes of common folk were corralled into trucks and disgorged into police cells to await their fate, many of them caught up in quotas ordered from above to "round up everyone who should be rounded up."

The story of Izgil's eventual escape is a nail-biting, but understated page-turner that delves deeply into the dystopian madness that characterises Uyghur life.

|

An Orwellian nightmare

Xinjiang became a war zone — the entire population mobilised for an as-yet invisible enemy. Bread sellers, market traders and bus stop monitors were kitted out with pith helmets, stab vests, military shields and oversized baseball bats.

Butchers' knives were emblazoned with the ID number of their owners and chained to the chopping board. Meanwhile, the local home guard — made up of stiletto-shooed mums pushing their stroller-bound children and unemployed youths sporting new uniforms — roamed the neighbourhoods wielding medieval instruments of torture.

Red armbands and whistles were de rigeur as 'joint antiterrorist manoeuvres' and 'stability preservation' drills were vigorously rehearsed through the day all in the name of a 'united line of defence against violent terrorists'.

Academics were sentenced to life imprisonment for their part in producing school textbooks that had not long before been commissioned and sanctioned by the government.

Those involved in government-approved translations of the Quran were taken away, only to be tried by kangaroo courts with no legal representation, and new lists of banned books and authors were issued daily. Harborers of those volumes were herded away for so-called re-education. Others including Izgil's friend and confidant, the Uyghur poet Perhat Tursun, were given lengthy jail terms.

A hope expressed by Izgil's friend Almas that this was "another gust of wind that would pass" was ill-founded and instead the campaign accelerated. No one knew who would be next. One by one his friends and colleagues were picked off, and Izgil was convinced that sooner or later his turn would come.

Having already served three years of so-called 'reform through labour' in 1996 for trying to take so-called 'illegal and confidential materials out of the country' over the land border with Kyrgyzstan on his way to study in Turkey, Izgil was sure that he must be somewhere on the wanted list.

The psychological warfare began for Izgil seriously in 2016 with good cop/bad cop invitations to tea to be friends with the local police to explain his connections with the outside world and personal relationships.

The Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti had already been sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014 followed by the disappearance of several of his students and hopes raised in 2013 that Xi Jinping's presidency might herald a liberal dawn were well and truly dashed.

Han Chinese were drafted into the province by the train load, Uyghurs were on the way to becoming a minority in their own land and the writing was on the wall for their language, writes Izgil. He began to feel an invisible net closing around him.

Banned items were growing by the day. Short wave radios were judged 'dangerous', sulphur from matches was classed as 'bomb-making material', popular Islamic names for children and villages were forbidden and common greetings such as As-salamu alaykum suddenly marked you out as being 'unreliable'.

The storm, which was expected to avoid the capital Urumqi, located around 1500 kilometres away from the vast Taklamakan desert that divides the traditional Uyghur region from its administrative centre, finally hit.

"We are finally free, but those we love most are suffering still, left behind in that tortured land"

Neighbours were forced to snitch on each other and given notebooks to record the comings and goings of those next door. Neighbourhood police with new powers marched around with clipboards, knocking on doors and taking those judged 'unreliable' away.

Twice a week house-to-house searches rooted out forbidden books, prayer beads, prayer rugs and their owners. So-called 'convenience police stations' appeared on every block, equipped with clubs, electric prods, and handcuffs and staffed by battalions of new recruits who pulled passing Uyghurs in to check their phones for incriminating apps and messages.

As the situation became more severe, they felt like they were being prepared for their inevitable fate. Izgil writes about the time when he and his wife were summoned to a police basement and every detail of their identity was scrutinized under the shadow of a 'tiger chair'. Blood and saliva samples were taken, their voices were recorded, their gait was measured, and their facial images and irises were scanned. All of this information was added to a vast database of every adult Uyghur in the region.

|

The long road to survival

Izgil's wife finally voiced her decision after the traumatic experience. "We need to leave the country," she said, but they faced a daunting challenge. All passports had been surrendered and the authorities were detaining anyone who enquired about overseas travel.

Izgil urged his wife to stay calm and not to search for him if he got arrested. He warned her not to waste money on trying to get him out and not to seek any external help. He believed that the situation was worse than ever before, and they were planning something ominous.

The Izgil family managed to escape to the US after coming up with a plan to use an invented epileptic condition for their daughter. They received help from a neurologist, a brain scan technician, and a hospital administrator. The farewell was cursory so as not to attract unwanted attention. Izgil didn't dare say goodbye to his own elderly parents as telephone calls were monitored. They were forced later to denounce their son.

They packed the entire contents of their lives into four suitcases and four small bags and were on their way. But in the process, forsaking their homeland weighed heavily on them both with Izgil's wife, Marhaba, asking, "Are we going to abandon our kinfolk?"

However, they had no choice. Izgil realized that his time would have come in the end, and staying would have achieved nothing. They cleared customs, much to their relief, soared over the triple-peaked Bogda mountain range and were on their way to freedom.

After landing, the future loomed dark and bleak. Neither of them had the stomach to start again, and as the days progressed, they could only watch helplessly as one by one, their friends and relatives disappeared into the camps and prisons of Xinjiang. They had had a narrow escape, but the "coward's shame" of having deserted their friends and family continued to be a dark shadow over their new life.

"We are finally free, but those we love most are still suffering, left behind in that tortured land. Each time we think of them, we burn with guilt. We will see these dear ones only in our dreams," Izgil writes.

The author is writing under a pseudonym to protect her identity

![The Chinese government has imprisoned more than one million Uyghurs since 2017 [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2024-03/GettyImages-1245667755.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=yo2Lb8YV)

![Tahir Hamut Izgil is a considered to be a pioneer of modern, avant-garde Uyghur poetry [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2024-03/GettyImages-1573745323.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=R9kvlL8E)

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News