Graphic feature: The perilous road to Gaza

Editor’s note: The author is writing under a pseudonym. All names in this article have been changed to protect individuals.

The decision was made as soon as the bombing stopped. Relatives told me the border was open, that my US passport would work, and if not, there would always be a way below ground. So, in early September, I packed my bags and arrived to a Cairo living and breathing as if it were not a city recently gripped by revolution.

| We watched the war on Gaza, now Gaza is watching the war on us. - Resident of Rafah, Egypt. September, 2014 |

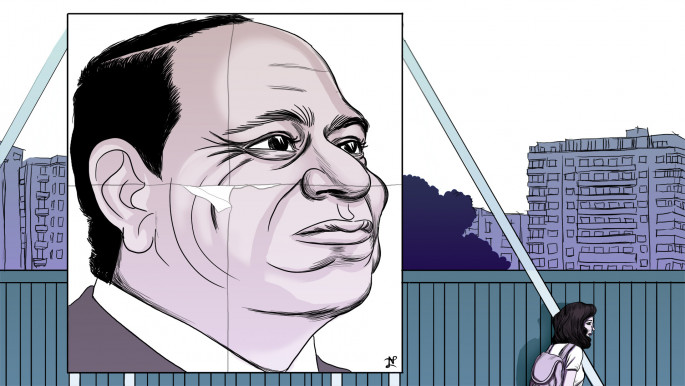

On the surface, daily life flowed along smoothly under Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s godfatherly face, which beamed down from posters and billboards throughout the city promising progress and stability. But after leaving Cairo for the Sinai Peninsula with a taxi driver – who turned out to be one of many guardian angels – the façade quickly melted away.

|

| Illustration: Anas Awad |

Crossing the Suez Canal can take hours. The bridge was closed in an attempt to contain Sinai’s instability, forcing us into a long line that snaked well past the military checkpoint. And so we waited two, maybe three, hours under the desert sun as we inched forward. My bags were taken for inspection, and I was left alone in the car until the driver (whom I will refer to as Abdu) noticed the line moving. He quickly pulled the car onto the ferry, asked if I knew how to drive while pointing to the gearshift, and ran back into the inspection room, leaving the car and me on the ferry, which pulled away right after he left.

I could not get far beyond the ferry landing, but a few kind-faced soldiers approached to help and asked where I was from.

“Falasteen,” repeated one soldier in an ill-fitting uniform who could not have been more than 16. His eyes glimmered as he and the others whispered to me, “Sha3b il jabareen” (The mighty people).

After crossing the canal and then a long desert road, travelers reach the sleepy coastal town of el-Arish, which is perhaps where the real trouble begins. The road leading from there to Rafah is under curfew from 4pm and so spending a night in al-Arish is often an unavoidable respite before the excitement of the border.

When we finally got back on the road the next morning, Abdu pointed out evidence of several explosions where local Bedouin groups had booby-trapped the road, blowing up Egyptian military vehicles and soldiers.

When we finally reached Rafah, I was turned away from the border twice by the Egyptian authorities [no hawiyah – The Israeli-issued Palestinian ID – no way]. Abdu’s family graciously hosted me, feeding me the same food I grew up eating and acquainting me with their town. Speaking Arabic and donning a black abaya what enabled me to remain and afforded me the freedom to move about with them; there were absolutely no foreigners or journalists, at least none that I could see.

|

| Illustration: Anas Awad |

I saw a Rafah with lush, green orchards and endless sand dunes that lined the brilliant blue Mediterranean coastline. But, despite the beauty, the sea and so many other parts of their lives had been either restricted or destroyed.

“We watched the war on Gaza, now Gaza is watching the war on us,” Abdu’s sister told me.

They secretly showed me entire neighborhoods named “Brazil” and “Canada” that had been wiped out by the Egyptian military to stop tunnel activity. Throughout the town, the fear and paranoia was palpable. Everyone spoke in hushed tones, and the few who traveled through the streets did so only out of necessity – lightly, quickly, silently.

Their own military besieged them under the pretext of protecting them and Egypt from Bedouin insurgents. Are they cartel-like insurgents? Mujahideen inspired by the Islamic State group? Resistance fighters disgruntled with the Egyptian government? No one seems to know for sure.

Abdu’s family was careful to differentiate themselves from the Bedouin. “They are Arabs,” they would say, “the Bedouin think we have no asl, no roots. But we are Palestinian.”

Technically, of course, they are Egyptians from Rafah and identify as such. Yet they live in a state of siege. Five tanks were parked in front of Abdu’s apartment building and several soldiers had turned the top floor of his building into a watchtower. No one could enter or leave the neighborhood or drive a vehicle after curfew at 6pm. It turned out that even my presence there was a risk for my hosts.

|

| Illustration: Anas Awad |

Abdu’s family urged me not to gamble with the tunnels and to stay as long as I needed. But the pull from my family in Gaza was strong; they had been working tirelessly on an underground passage once we all realized the border crossing was hopeless. So after nightfall, with curfew in full effect, the operation commenced.

I will save the story of how I got through for next time. For now, I am still trying to make sense of the curious state of affairs visible from any vantage point – above or below ground.

This Rafah, a place and a people split by an unstable border between Egypt and Palestine, is riddled with contradictions. There is a confluence of powers, of multiple state and non-state actors, some more transparent than others, that cause these borderlands to continue to shift, consuming whoever might be in the way. These dynamics force residents to constantly negotiate and renegotiate their national and ethnic identities, their political allegiances and their day-to-day survival.

With news now of an ever-widening buffer zone, my cousin who lives on the Palestinian side of Rafah (let us call him Mahmoud) told me a few days ago (several weeks after my return to the US) that they have no windows left in his house. The explosions from the home demolitions in Egypt surpassed even the intensity of the Israeli bombardment during the 51-day assault on Gaza this summer. Absolutely nothing is coming through the tunnels anymore – not even cigarettes.

This is the same cousin who secured my entry and exit each time through the tunnels. A former tunnel smuggler, Mahmoud is intimately familiar with the landscape. It was he who received me when, after quite a bit of maneuvering through Rafah-under-curfew, I finally made it to the tunnel entrance. I was brought into a covered space with a depression in the ground lined with stones, which were lifted one-by-one allowing the earth to open.

The opening finally revealed Mahmoud, wide-eyed and sweaty, who yelled at me: “I have been waiting an hour for you!”

|

| Illustration: Anas Awad |

Next time: Tunnel tales

This was the third of four tunnels I would experience, each tunnel progressively less developed than the previous, as if in harmony with the conditions above ground…