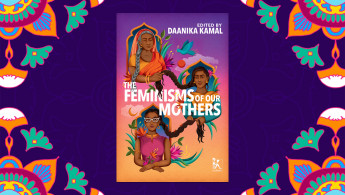

The Feminisms of our Mothers: Unpacking generational rage

What’s your worst fear in life?

For some Pakistani women, it’s ending up with lives like their mothers.

Amna Baig touches on this sentiment in, Caged Within, which is part of an anthology titled The Feminisms of our Mothers: Essays from Pakistan.

Published internationally this month by Zubaan Books and edited by Daanika Kamal, the collection of 20 essays explores women’s relationships with their mothers, feminism, and most importantly, the intersection of the two.

"I learnt everything I know about feminism from my mother... We don’t always agree, but we’ve always been able to have very open conversations about those disagreements, those differing perspectives, and I’ve always seen our conversations as being productive, not obstructive"

Some essays refer to feminism as “that F word” that is viewed to be antithetical to Pakistani culture. It’s seen with scepticism and perceived to be some sort of Western colonialist agenda to break up the nuclear family – and by extension, cause havoc on society.

Kamal reveals that she was in fact advised not to put “feminism” on the cover, as it could detract potential readers from picking up the book.

Thankfully, she didn’t acquiesce. Kamal says it was vital for the title to include “feminisms” – the plural form of the word – to acknowledge that interpretations of the term are as diverse as the women they refer to.

It was also important for Kamal to centre mother-daughter relationships as a focal point of the convergence – and divergence of these feminisms. “I learnt everything I know about feminism from my mother,” she tells The New Arab.

“We don’t always agree, but we’ve always been able to have very open conversations about those disagreements, those differing perspectives, and I’ve always seen our conversations as being productive, not obstructive.”

|

Kamal has extensive experience in human rights law, specialising in access to justice and the protection of rights of marginalised people, and she recently completed her PhD in law with a focus on domestic violence cases in Pakistan.

“I wanted to bring forth the stories of daughters who are working towards the advancement of women’s rights through different sectors and fields in Pakistan,” she says of her criteria for selecting contributors.

While the women who made this book a reality may be Pakistani, readers of other backgrounds will easily draw parallels with their own cultures and families.

Contributors explore their relationships with their maternal figures and express how they have informed, inspired or completely clashed with, their ideals regarding the rights, responsibilities and realities of women.

Kamal notes that the current Aurat March (“Women’s March) feminist movement in Pakistan is often pinned against past movements and that this widening gap is counterintuitive to the quest for gender equality in the country.

“I think the mother-daughter relationship is a great, symbolic way to address that gap,” she says.

Many of the essays describe how women are often the upholders of patriarchy, continuing the cycle either because it’s all they know, or because, perhaps, they think it would be unfair for their daughters to receive liberties they never did.

In Love Unspoken, Love Unheard, Aimun Faisal writes that burdens carried by her mother for decades were inherited from her grandmother – and that she too, is expected to inherit them.

In her essay, All the Women in Me Are on Fire, Maria Amir classifies women as containers or shapes – either circular or square.

“For the women of the circle, pain is legacy, and legacy must always be passed down,” she writes. Squares, meanwhile, are self-contained, finite, and actively work to stop the cycle from repeating. “All of these circles that we cannot square, have amounted to various shapes of living; internalised rage passed down across generations,” she writes.

Amir writes that this rage has been “suppressed”, “sidelined” and “swallowed,” while Tooba Syed, in (Un)mothering, writes that her female ancestors’ tormented souls are “raging” with her, from their graves.

"Incredibly relatable and deeply enlightening, The Feminisms of our Mothers brings important discussions about gender and culture to the fore"

Numerous essays mention the typical pattern of Pakistani women excelling in school, only for their education to be interrupted by a marriage proposal. This expectation that women should sacrifice one future for another is seen as a form of torture by Baig, who claims that keeping a woman from her potential can be more devastating than physical abuse.

Ayesha Izhar, in her essay, Yearning For a Genderless Life, says that “sacrifice” is a word that women grow up with “like a tumour attached to their bodies”. What’s worse is that these sacrifices are not made for great causes, but for routine chores – “for the bare minimum that can be done by any human but are burdened on women simply because they are women,” she writes.

Some women endure this fate silently, while others quietly resist. Silent feminism is a concept that many of the writers delve into, acknowledging that their mothers may not have been vocal about their feminisms but were dealing with the gender battles of their times and furthering female empowerment in their own ways.

For twin contributors Amna and Mariam Shafqat, it was their mother’s decision to disallow books that tell stories of damsels in distress and romanticise female sacrifice and subjugation.

For Sabah Bano Malik, one of Pakistan’s first plus-sized models, the fact that her mother didn’t push her to lose weight in a society obsessed with women’s appearances and marriage marketability, marked a feminist act. In “The evolving feminist” she writes, “The reason I can do much of what I want is that my mom, the reluctant feminist, the quiet feminist, the feminist without a label, allowed me to do it.”

|

Complex and at times contradictory emotions are evident throughout many of the essays, as women grapple with the mixed feelings they have towards their mothers.

Sometimes they’re loved; other times, they’re hated. “At best, she is a decent person who has been wronged by life; at worst, she is my tormentor,” writes Zoya Rehman in When They Suffocate. She states that her mother is both her biggest teacher of feminism and also her biggest detractor, the first abuser in her life and also the first source of warmth, her first home – and also her first taste of hell.

Many contributors acknowledge their privilege and see twinges of regret – perhaps even envy – in the eyes of their mothers, who can’t help but compare their pasts with the more liberated lifestyles of their daughters. Some even undergo the task of helping their mothers unlearn internalised misogyny. “Their generation did not have the words to make sense of their marginality,” writes Manal Khan in (Dis)associations.

For the most part, writers pay homage to the females in their families through their thoughtful, reflective and even forgiving essays that unpack generations of trauma while recognising how they have been shaped by their female predecessors.

In her essay, When the Maina Bird Sings, Kamal writes, “My feminist identity is an amalgamation of the histories of my mother, my mother’s mother and the mothers that came before. Sometimes a transmission and other times a transition.”

She explains that while the publishing experience has been enriching, it has also been challenging – particularly with censorship: “There were difficult realities to contend with, especially to get the book into the Pakistani market, that was, quite frankly, at odds with the feminist ethos that this book so boldly embodies.”

One essay, What is Behind You by Sadia Khatri, which discusses abortion, didn’t make it into the Pakistani edition of the book, published by Liberty, but is part of the international edition published by Zubaan Books.

Incredibly relatable and deeply enlightening, The Feminisms of Our Mothers brings important discussions about gender and culture to the fore.

Each essay opens up a window to the complexities, intimacies and inner dilemmas of its writer, offering consolation, advice and solidarity to readers who can’t help but see snippets of their own life stories within these pages. “My choice to do this book as a non-fiction, literary anthology rather than an academic one – despite being an academic myself – was precisely for this reason,” says Kamal.

“It needed to be accessible.”

Hafsa Lodi is an American-Muslim journalist who has been covering fashion and culture in the Middle East for more than a decade. Her work has appeared in The Independent, Refinery29, Business Insider, Teen Vogue, Vogue Arabia, The National, Luxury, Mojeh, Grazia Middle East, GQ Middle East, gal-dem and more. Hafsa’s debut non-fiction book Modesty: A Fashion Paradox, was launched at the 2020 Emirates Airline Festival of Literature

Follow her on Twitter: @HafsaLodi

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News