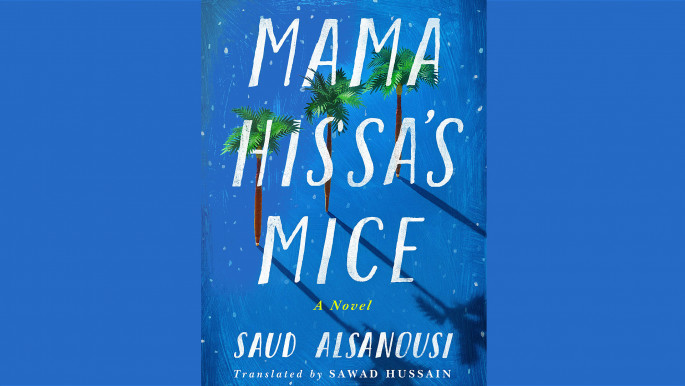

A dystopian vision of Kuwait: Mama Hissa's Mice

"With every catastrophe that's heaped upon our heads, we hope that it'll be the worst and last one. But disasters are funny things: they come charging at us one after the other, eating our hopes alive. They rub their middle finger in the face of the alleged cease-fire."

As I turned the final pages of Saud Alsanousi's novel Mama Hissa's Mice, I found myself mourning for a country I've never visited and people who only exist within the fictional realm of the story.

Translated into English by Sawad Hussain, Mama Hissa's Mice is a speculative fiction novel that shuttles between the past and present, telling a decades long story from the perspective of a narrator called Katkout.

This is the kind of novel where you slowly become acquainted with the characters, and once you fully absorb their story, something in you shifts and changes.

Alsanousi's portrayal of Kuwait is nostalgic, evoking key moments in recent history that have been impactful for not just Kuwait but the Gulf region in general.

The present-day setting of the novel is the year we are living in currently – but it is the near future that Alsanousi imagined when he published the novel back in 2015.

|

Alsanousi's portrayal of Kuwait is nostalgic, evoking key moments in recent history that have been impactful for not just Kuwait but the Gulf region in general |  |

Mama Hissa's Mice was promptly banned in Kuwait following its publication, and remained off the shelves for several years, until the author won his case against the censorship.

Mama Hissa's Mice takes on a dystopian tone in its depiction of Kuwait as a nation that is burning in the throes of civil war – strange creatures called corpse catchers have descended to terrorise the living, bombs erupt and fires are catching leaving behind nothing but ashes.

|

|

| Mama Hissa's Mice was promptly banned in Kuwait following its publication |

Decades of hatred between major sects of Islam, political instability with neighbouring nations and the aftermath of the Gulf war, had weakened Kuwait as a nation, ultimately leading to tensions that have risen prompted by propaganda, and intolerance between the communities.

Katkout laments about the hatred that was spilling out publicly, "Our sectarian clot had reached the point of no return. At a time when the person being eulogized was in the land of the dead, we split up into too, preoccupying ourselves with his fate – in heaven; no, in hell – when in fact we were the ones in hell after living out our lives hiding this hatred that was within us…"

Mama Hissa's Mice is a story where the personal aligns with the political, making this a timely and important novel, particularly in the face of global policies and sentiments that have caused an increase in intolerance and insensitivity.

In the novel, Katkout grows up alongside his friends in their close-knit neighbourhood called Surra. They all grow up listening to Mama Hissa's stories, and share influences of popular culture that eventually define their childhood and inform their worldview.

As adults, witness to the horror that their beloved country has been subjected to, Katkout and his friends form a protest group called Fuada's Kids, inspired by a character in their favourite TV series Rest in Peace, World. Some of the show's scenes are shot in their own street, so it automatically becomes the TV series that they identify with.

|

Decades of hatred between major sects of Islam, political instability with neighbouring nations and the aftermath of the Gulf war, had weakened Kuwait as a nation |  |

The comical depiction of characters in a mental asylum includes Fuada, a deranged woman who warns everyone about the plague that the mice are bringing.

|

|

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: Tequila Leila and the misfits: Elif Shafak's 10 Minutes 13 Seconds In This Strange World |

The image of the characters Mahzouza and Mabrouka running away from the dangerous mice is etched in the minds of Katkout and his friends.

As Fuada's Kids, the group broadcasts messages that warn people about the plague that is spreading across the nation. That plague is the sectarian politics that has been turning brother against brother for decades.

On their radio broadcast, they play the same old songs that had evoked the image of an ideal Kuwait, and although they may be disillusioned men, they hope that Fuada's Kids can create ripples of change for the coming generations.

Two major narrative threads are woven in Mama Hissa's Mice – the Present Day chapters record the course of the day that is unfolding for Katkout, after he wakes up on a parking lot asphalt with blood and pebble in his mouth.

As he slowly regains consciousness and balance, Katkout begins to drive around the city looking for his friends Fahd and Sadiq. He revisits the old neighbourhood Surra, where he grew up, where the memories of his past reside.

The alternative narrative in the story are chapters from Katkout's novel, The Inheritance of Fire. Life and art collide as Katkout retains the original names of the people the characters are based on – the fictionalised version is also the story of Katkout's past.

These chapters reveal Katkout's childhood years, his friendships that he forms and the moments that test those friendships.

|

Mama Hissa's Mice is infused with a deep sense of nostalgia for the past, evoked by memories that are painful for Katkout to recall |  |

An important section of the story details his experience during the Gulf War where he'd moved into Fahd's home. The narrative reveals the people and places that he becomes attached to.

One of them is Mama Hissa, the intimidating matriarch who tells stories that eventually inform Katkout's worldview and beliefs.

Another important person in his life is Fawzia, Mama Hissa's daughter whose combination of ill health and controlling brother don't allow her to live an active life, and so she spends her time eating sweets and reading romance novels that her brother has strictly forbidden.

Mama Hissa's Mice is infused with a deep sense of nostalgia for the past, evoked by memories that are painful for Katkout to recall. Often he laments the hold of the past and memory over him.

As the two sections alternate, the past often interrupts key moments unfolding in the present, imitating the way Katkout is constantly haunted by his memories.

|

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: Love, slavery, madness and abuse: Celestial Bodies |

An important theme in Mama Hissa's Mice centers on the deeply problematic culture of censorship and control practiced not just by the government, but also adults in their daily dealings with children.

The opening prologue depicts Katkout as an eager young boy whose sincere yet incessant questioning is a source of annoyance for his mother who just wants to take a nap.

Over the course of the novel, Katkout asks questions that are not always answered and sometimes the response is a resounding slap.

Alsanousi writes, "At times, ignorance can be a blessing. In our dialect, a child is jahil, ignorant, and jahhal like us were living in bliss, the sweet bliss of not knowing. Once I had grown up a little, I became preoccupied with forbidden questions."

The forbidden questions of the adolescent years clear the path for the youth who is growing into an adult and becoming aware of their beliefs and the world around them. This near-adult begins to the question the behaviour and decisions of the state, the adults or those in charge – an activity considered distasteful by the status quo.

Katkout, who has grown up listening to Mama Hissa's stories, understands the power of storytelling and inserts his questions into the stories he writes for Fawzia.

Later, when he begins to write for Al Rai, a newspaper, he's astonished by the vitriolic response of readers that is as bad as censorship, "I didn't understand how the reader was engaging with the writer. The reader had become a deadlier censor than the censors themselves. People were doing wrong, I was writing about it, and others were blaming me for writing it!"

This sentiment resonates loudly and ironically when you consider the censorship Alsanousi had to fight back against, to allow his cautionary tale to reach its readers.

Mama Hissa's Mice also raises questions regarding censorship when Katkout's publisher advises him to remove several chapters of his novel in order to avoid the book getting banned.

|

Mama Hissa's Mice also raises questions regarding censorship when Katkout's publisher advises him to remove several chapters of his novel in order to avoid the book getting banned |  |

The prologue of novel is written brilliantly in the way it captures some of the recurring themes: violent occurrences, censorship and the child's gaze upon the adult.

In the prologue, it is briefly noted that a café bombing had resulted in the death of Mama Hissa's husband. Similar shocks and losses are scattered all over the novel, like the stones that Katkout and his friends collect from construction sites, or debris left over from bombings.

In present day, as Katkout makes his way across the city, to reach his friends and make sure they're okay amidst the violence that has erupted, he comes across a bridge that separates the warring Shia and Sunni sides.

|

|

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: Other Words for Home features the strong Muslim girl we've been looking for |

He calls the bridge a "barzakh, a no man's land between two hells". What makes Katkout the perfect narrator for the story of Kuwait, a nation that is fragmenting under the frightful power of sectarian socio-politics, is his lifelong friendship with Fahd and Sadiq, two boys who belong to opposing sects of Islam (whereas Katkout himself has been taught by his mother to identify as a Muslim).

Katkout has witnessed the tensions that have fraught their group since childhood; these troubles have haunted him all his life.

He hates the game of tug of war which places him in the middle, because it represents the troubled friendship that he shares with the two boys, "Every time you switched sides, sometimes pulling with Sadiq and other times with Fahd. You hated being in that position, between the two, with no choice but to join one against the other in a game solely based on strength."

The divide is echoed in the endless bickering between Fahd and Sadiq's fathers, Am Salim and Am Abbas – neighbours who never agree on anything.

The only time the Shia and Sunni sides agree upon something is when a fatwa is issued declaring Fuada's Kids as misguided, "Both of them, who never wish the other a happy first day of Eid because they each have different first days of Eid. Neither of them can agree on prayer timings, or the percentage of zakat, or burying their dead in one cemetery. Both of them can't agree on anything except shunning the other. In a bid to shut us down – us, whose throats have grown hoarse from continually calling for equality and peace – both of them have now agreed on something for the first time."

Saud Alsanousi's novel presents a scenario where the ill sentiments that Islamic sects bear for each other has reached a breaking point.

The dystopia that Katkout wakes up to at the start of the novel is the result of decades old bitterness, anger and hatred between groups who, ironically, belong to the same religion. His message is clear.

Mama Hissa's Mice is a truly remarkable novel and definitely one to add to your list if you're looking for thought-provoking books set in the Middle East.

Reading it will be slightly challenging for someone who is unfamiliar with Kuwaiti culture and the socio-politics of the Islamic sects, however Sawad Hussain's translation makes much of it accessible for a reader in unfamiliar territory.

Katkout's perspective is one that is deeply personal and emotional, making this novel an unforgettable story of friendship and rebellion.

Sumaiyya Naseem is a Bookstagrammer and freelance writer and editor who specialises in Middle Eastern and Muslim stories. In 2019 she joined the Reading Women Podcast as a guest contributor to talk about South Asian and Middle Eastern narratives.

Follow her on Instagram: @sumaiyya.books

The New Arab Book Club: Click on our Special Contents tab to read more book reviews and interviews with authors: