‘The British Museum will be written in black’: Demanding the return of the Rosetta Stone

The effects and consequences of colonialism live on for centuries after its death. They exist overtly and covertly, as previously colonised nations grapple with reasserting their rights, identities, and traditions to move on from their traumatic past, change their present-day trajectories and take back what is rightfully theirs.

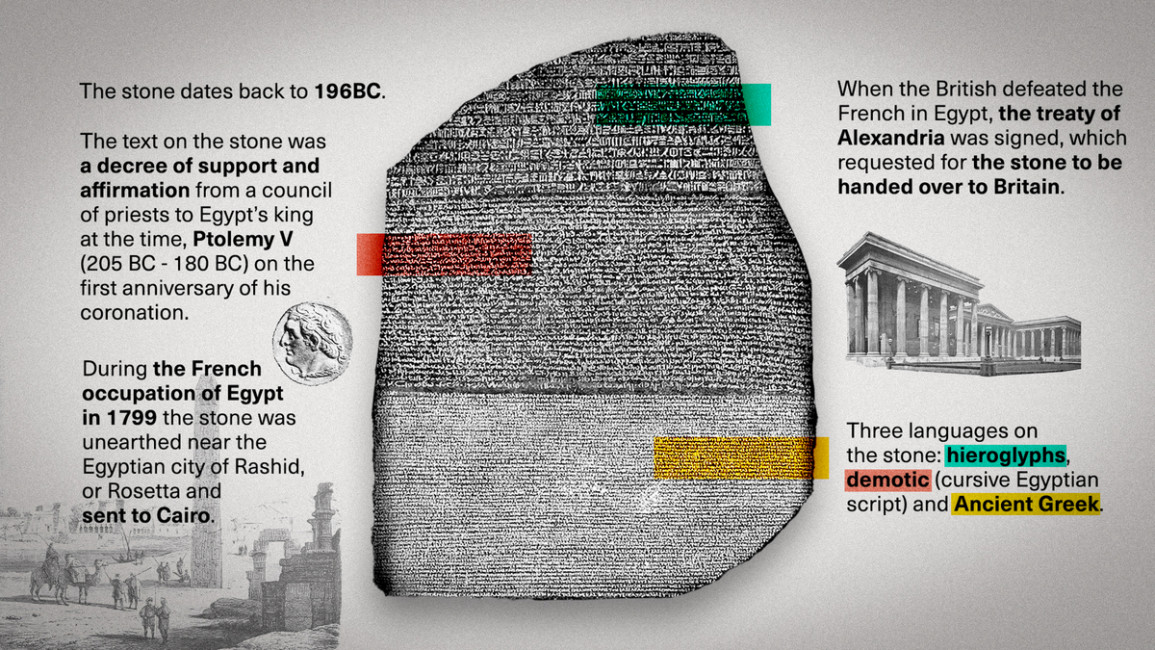

The Rosetta Stone is a 2,200-year-old historic Egyptian artefact that was key to deciphering the mystery of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, allowing the writing system to be decoded and clearly understood for the first time in centuries.

It is stored in the British museum however, 220 years after its arrival in the UK, Egyptologists, Egyptian archaeologists and activists across the world are calling for its return to the historic north African country.

The origins of the stone and its significance

The Rosetta Stone bears inscriptions of three texts in Hieroglyphs, Demotic – a cursive Egyptian script – and Ancient Greek. Using the assumption that the texts would share the same meaning, the stone was used by Frenchman Jean-Francois Champollion to decipher the Hieroglyphs, before he shared his discoveries crucial to understanding them in 1822.

The text on the stone was a decree of support and affirmation from a council of priests to Egypt’s king at the time, Ptolemy V (205 BC - 180 BC) on the first anniversary of his coronation. Egyptian archaeologists also say the decree exhibited the priests’ gratitude for exempting their people from taxes.

It is important to note that despite the stone providing a breakthrough, almost a millennium before it was discovered, Arabic scholars had started to examine hieroglyphs on other Egyptian monuments and tomb paintings in attempts to crack its code.

The discovery of the stone and its shipment to Britain

During France’s occupation of Egypt, French Military Leader Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops unearthed the stone in 1799 while digging in Fort Julien near the city of Rasheed (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta – where historians believe the stone was likely used as a building material. The troops then sent the stone to Cairo after realising its significance.

However, when the French were defeated by the British in the North African country in 1801, they signed the Treaty of Alexandria, which ruled that the stone, alongside other Egyptian antiquities, should be handed to Britain.

"During France’s occupation of Egypt, French Military Leader Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops unearthed the stone in 1799 while digging in Fort Julien near the city of Rasheed (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta"

In 1802 the stone arrived in Portsmouth and at the bequest of King George III, it was installed at the British Museum, where it remains today and is considered one of the institution’s most famous possessions.

Calls for the return of the stone to Egypt

However, Egyptologists, Egyptian archaeologists, and activists across the world are now demanding that the stone is returned to Egypt.

Repatriate Rashid is a campaign led by a group of Egyptian archaeologists calling for the return of the stone, and 16 other objects taken as "spoils of war", to Egypt. They opened a public petition last September, which, they told The New Arab, has gathered 4,142 signatures so far.

"We can’t change history but we can correct it"

The group argue that Egypt had “no sovereignty over its own cultural heritage”, as it "did not sign" the Treaty of Alexandria. They also say that the articles in the treaty were “in violation of the law of nations, customary international laws, and Islamic laws applicable at the time” – making the sequestration of the Rosetta Stone “an act of plunder” and a “transgression on culture property and cultural identity… [as] its presence in the British Museum supports endeavours of past colonial violence”.

“We can’t change history but we can correct it,” the leader of the petition and acting Dean at the Egyptian College of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Dr Monica Hanna, told The New Arab.

Dr Monica plans to take her “legally binding” petition to the Egyptian Prime Minister, currently Mostafa Madbouly, next September – one year after its release – as she says he is the “only person… who has the legal valid agency to apply through the ministry of foreign affairs for the restitution of the objects”.

She also told The New Arab that the office of the Egyptian public prosecution has been in touch with her team, to prepare legal steps for the Egyptian Prime Minister to request the return of the objects, from the British government.

She hopes that the stone will be sent back to its finding place in the city of Rasheed. “I think objects should be part of the community and should be part of the economic sustainable development for communities to have strong meaningful ties,” she told The New Arab, stating strong marketing plans could be made around the destination to enhance it.

'Divided voices' sharing similar sentiments

Egyptologist and former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Zahi Hawass has also released a separate campaign for the return of the stone – and the Dendera Zodiac ceiling, held in Paris at the Louvre – and released a public petition for it on 19 October 2022.

Unlike Monica, he is calling for the stone to be placed in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, Cairo, ahead of its scheduled opening in November 2022. However, Dr Monica claims that Hawass’ move has derailed her team's goal by "dividing the voices" stating … "it's enough that we’re already up against something as big as the [British] museum".

Setting up the petition almost one month after Repatriate Rashid, Hawass’ public call has gathered almost 18,000 signatures in just one week.

The former official – who says he brought 6,000 Egyptian artefacts from around the world back to his country during his time as a minister – also argues that the stone was unlawfully taken from Egypt and gifted to Britain by colonisers who “had no right” to them, stating that the Treaty of Alexandria was signed “in a time of imperialism” which he demands is finally brought to an end.

"It seems absurd that the British Museum would continue to hold on to such a blatant symbol of its colonial past”

The Egyptologist has stated that it “seems absurd that the British Museum would continue to hold on to such a blatant symbol of its colonial past” and told The New Arab he strongly believes in the power of the people to return the stone. “I don’t think the British Museum will be able to [reject the request] because its name will be written in black in history… it will be a shame for them”.

“The Rosetta Stone… is the icon of our Egyptian identity… therefore I really believe that it should be in the grand museum when we open it,” he told The New Arab, stating his plans to formally write to the British Museum and the Louvre to request the “unique” items’ return once his petition achieves 100,000 signatures.

The British defence

The British museum justified the Rosetta Stone’s placement in their institution in a statement to The New Arab, saying “representatives of the Egyptian, French and British governments signed the Capitulation document, which travelled to Britain with the Rosetta Stone”.

“We enjoy a long-standing and collaborative relationship with the Egyptian Government… it was agreed that 21 antiquities – including the Rosetta Stone – collected by the French would be handed over to the British as a diplomatic gift,” the institution told The New Arab.

“When they say the Egyptians are the Ottomans it’s even worse, it means they have no clue who the Egyptians are and so should not even have a collection of Egyptian objects”

In Robert Thomas Wilson’s 1803 book History of the British Expedition to Egypt, the author outlines the signatories of the treaty, which are listed as British Admiral Keith, Anglo-Irish Lt.-General Hely-Hutchinson, French General-in-Chief Abdoullah Jacques Francois Menou, British Lt.-Col. James Kempt and Ottoman Capitan Pasha Hussim (Huseyin). No other signatories are listed, Dr Monica also stated that no Egyptians signed the document.

“The Egyptians did not sign, this is very clear,” Monica stated to The New Arab, calling the museum’s statement “a blatant lie”.

“When they say the Egyptians are the Ottomans it’s even worse, it means they have no clue who the Egyptians are and so should not even have a collection of Egyptian objects.”

Activists' stance

Activists have also backed Hawass and Dr Monica's claims, stating their beliefs that "it’s not fair" that the stone can be more accessed by a British person, than an Egyptian person and that its placement in the British museum perpetuates "harmful" beliefs.

“Not only are these European countries still profiting from their colonial past by filling their museums with stolen stuff, but they also have incredibly tight visa regulations for the very people they’ve stolen from,” activist Jasmine told The New Arab.

“I think keeping the stone in the British museum legitimises past colonial endeavours… and perpetuates the idea that the artefact is safer there. Returning the stone to Egypt would be a symbol of decolonisation… while the profit from tourism to see this piece would stay in the country, maybe supporting further research,” she added.

Although it is not yet certain whether the Rosetta Stone will be returned to the country of its finding place, whether to Raseed or to Cairo for placement in the Grand Egyptian Museum, it is undeniable that as time goes on, the fire within Egyptians to rewrite the damaging effects of their colonial remains as fervent and alive as ever.

Aisha Aldris is a staff journalist at The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @aishaaldris