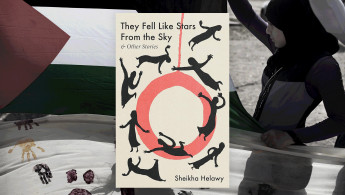

Sidelined by society, Sheikha Helawy's short stories animate the lives of Palestinian Bedouins stuck in limbo

Amid constant and violent deracination, the stifling patriarchy, and the radiance within the mundane, women remain lambent in They Fell Like Stars From the Sky and Other Stories.

Award-winning author Sheikha Helawy has crafted 18 short stories in which young women and girls soliloquies, memories, and tragedies are celebrated and scrutinised.

The literary canon is rife with Palestinian tales that have expounded on its trauma, resilience, and people.

However, translated by Nancy Roberts, Helawy has animated the life of Palestinian Bedouins and the life that prevails in their villages. She is one of the few authors who has revealed an intimate portrait of the inner worlds of Bedouiness to a global audience.

"Helawy focuses each story on the spirit of one or two girls. The psychological acuity with which she writes demands to be lauded. Adolescence is a perplexing transition for girls, and the added trauma of occupation and societal fixation on female bodies and chastity only convolutes their worlds further"

Helawy herself is from the forgotten village of Dhail El E'rj. Roberts prefaces that the residents of this village, including Helawy, were forcibly displaced by the Israeli occupation.

The town was eradicated, delineated as unrecognised, and replaced with an Israeli railway. Thus, Helawy has reanimated the people of this plundered town and the little girl within her who resisted and triumphed. Her lyrical vignettes are interlaced with Bedouin dialect and examine those girls just entering into womanhood to those with years of wisdom.

She pens stories in which their experiences are universal yet distinctive to Bedouin's existence. Not only are these tales a homage to her roots, but they were written as a spiritual purging to reconcile, dismantle, and confront the cultural stereotypes that sought, yet ultimately failed to diminish, women.

|

The ethics and principles governing these villages' girls are subtly interwoven. The tales are succinct, each merely three to four pages long. Many of them explore the psyches of adolescent girls coming to terms with their changing bodies and minds and the contradictory regulations imposed on them.

In the first story, Haifa Assassinated My Braid, a young girl convinces her mother to take her to the salon to cut off enough hair so she can no longer boast the braids precious to girls of her Bedouin culture.

She is a student at a school in Haifa and is relentlessly teased for all the features that betray her Bedouiness. So, in an effort to transiently disavow her identity and become a Haifa girl, she chops off her braid despite the Bedouin mentality equating braids with virginity.

In the eponymous story, They Fell Like Stars From the Sky, a group of boys tie a tire to a tree to create a makeshift swing that provides the illusory effect of flying over the neighbouring Jewish settlement.

This innocuous pastime of children worldwide has turned into a scandal. Jawaher, the young girl the story centres on, contemplates the repercussions of enjoying the swing and decides to get a taste of the air above with her friends. Such an act is borderline shameful for growing women like themselves. In their defiance, the swing snaps, scattering the girls like fallen stars, injuring Jawaher, and bringing dishonour to her mother.

In Pink Dress, another girl haphazardly shaves her leg hair in contempt of her mother's anxiety so that her feminity may illumine through her dress.

"Many of the other tales contemplate love, marriage, and family. How are relationships defined in a society consumed with a woman's virginity or in the precarious environment under apartheid?"

Helawy focuses each story on the spirit of one or two girls. The psychological acuity with which she writes demands to be lauded. Adolescence is a perplexing transition for girls, and the added trauma of occupation and societal fixation on female bodies and chastity only convolutes their worlds further.

An unnamed character from I'll Be There is caught in limbo between the oppressive rules of the British Nun at her school and her puritanical Bedouin mother. Her only crime is that she enjoys jewellery and music.

Selma is a girl on the edge of puberty whose bosom is blooming in the tale The Door to the Body. Her burgeoning femininity prompts caustic arguments between her parents about whether they should send her to boarding school. As she ponders with innocence, "What bothered her most was her parent's preoccupation with a part of her body that didn't even mean much to her!"

Throughout the collection, we see that the Israeli occupation is not a central force in this collection. However, key players are insidiously intertwined in the characters' lives, such as the British nuns and the bordering Israeli settlements that boast luxuries near dwindling villages. While their shadow eclipses the prosaic concerns of teenagers, we are made to witness the silent but resounding fortitude of the Palestinian people.

Many of the other tales contemplate love, marriage, and family. How are relationships defined in a society consumed with a woman's virginity or in the precarious environment under apartheid?

Ali is the meditation of a young man who ponders on his beautiful wife, Wadha, comparing her to coffee beans. He asserts that coffee beans require an expert, and so does a woman, only to learn that his wife's heart is beholden to another man named Ali. A dead woman's body horrifies the village elders when her body is found to be adorned with snake tattoos.

A private act for the sensual pleasure of her husband haunts and scandalises those she leaves behind. Hasna is told, "We don't have girls who fall in love," in Umm al-Zeinat. A betrothed teenager is ridiculed for the love of her donkey, and Habiba's grandmother's devotion to singer Umm Kulthum sustains her. Love and connection survive pillaging, tirades, and war in Helawy's world. Moreover, it manifests beyond romance and through the bonds of feminity and life itself.

The tales' brevity affects the sentiment of entering someone's private memories and consciousnesses. They are an eloquent sketch of the interminable metamorphosis' of a woman's identity and the power she possesses to resist.

When girls experience puberty, they leave behind their childhood to enter a life driven by ambiguous morals while navigating through their unique womanliness. It is a harrowing task further compounded by the perilous political atmosphere of life under occupation.

The individual is shaped by discrepancies in their national identity and constraints of tradition, so the women in Helawy's stories provide a catharsis for the readers. Being cognizant of oneself and how your environs permeate your psyche requires adroitness and candour, a skill that Helawy has conquered.

Noshin Bokth has over six years of experience as a freelance writer. She has covered a wide range of topics and issues including the implications of the Trump administration on Muslims, the Black Lives Matter movement, travel reviews, book reviews, and op-eds. She is the former Editor in Chief of Ramadan Legacy and the former North American Regional Editor of the Muslim Vibe

Follow her on Twitter: @BokthNoshin

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News