In the age of counter-revolution, Arab autocracies are fighting back

The defeat of the Arab Uprisings that started in 2010 in Tunisia and spread to other countries in the Arab world was, in part, the result of the revolutionaries’ own failures.

At the same time, and perhaps more importantly, it was also the consequence of the successful strategies adopted by those who espoused counter-revolution to thwart political change.

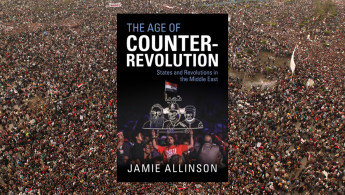

This is the idea at the core of Jamie Allinson’s book The Age of Counter-Revolution: States and Revolutions in the Middle East, where he explores the mechanisms that allowed the pre-Arab Spring elites to weather the storm of popular mobilization and remain close to power.

"Allinson finds similarities between the cases of Syria and Bahrain, on the one hand, and Yemen and Libya, on the other. The two other countries he approaches jointly are Tunisia and Egypt"

The concept of an “Arab Counterrevolution” is almost as old as the term “Arab Spring.” This notwithstanding, Allinson’s work provides an original analytical framework that generates relevant findings in its comparison of the different shapes counter-revolution took across the Middle East.

Allinson, who is a senior lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Edinburgh, convincingly argues that counterrevolutions are driven by elements of the old regimes who, nevertheless, need to gather a certain degree of mass support if their counter-revolutionary ambitions are to succeed.

In the cases of Syria and Bahrain, the channels to mobilize popular support for the counter-revolution were relatively obvious: in both countries, sectarianism was exploited to prevent the revolution from materializing.

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) February 21, 2023 |

Whereas in Syria the al-Assad government presented the opposition as a Sunni threat against the Alawite minority to which the President belongs, in Bahrain the Khalifa monarchy framed the protesters as a Shia attack against minority Sunni rule in the island country.

Both the Syrian and the Bahraini governments successfully mobilized their minorities in a counter-revolution that received certain support from below, but they still needed external intervention — Russia and Iran in the case of Syria, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Peninsula Shield Force in the case of Bahrain — to re-impose themselves.

If the role of external actors was important in Syria and Bahrain, it was essential in Yemen and Libya. In 2012, Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh was removed from power.

The previous year, Muammar Gaddafi had been killed by rebel Libyan militias. This complicated the coordination of the former regime elites around a single counter-revolutionary project. In Yemen and Libya, it was not easy to distinguish between pro- and counter-revolutionary groups.

As Allinson explains, the prospects of meaningful reforms in Yemen were thwarted by the Saudi Arabia-imposed deal to replace Saleh with his vice-president Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi in 2012.

Meanwhile, the popular demands for change in Libya soon fell victim to the dominance of armed militias in the post-Ghaddafi context. Moreover, the convulsed internal contexts in both Yemen and Libya left ample space for foreign intervention. Allinson notes that “Saudi Arabia and the UAE formed the strategic core of the main counter-revolutionary axis.”

In Yemen, a Saudi-led coalition intervened in 2015 to stop the advances of the Houthi movement — hardly a revolutionary group themselves, at least not in the sense of promoting political and social rights for the population. Meanwhile, the UAE has been supporting the Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar since 2014.

As we have seen, Allinson finds similarities between the cases of Syria and Bahrain, on the one hand, and Yemen and Libya, on the other. The two other countries he approaches jointly are Tunisia and Egypt.

On the face of it, both cases present significant divergences — Egypt only celebrated a free presidential election in 2012, whereas Tunisia has been holding democratic elections for ten years after the fall of Ben Ali.

However, for Allinson, a full revolutionary process encompasses not only political change but also a socioeconomic transition.

And he argues that Tunisia, alongside a real political revolution, experienced a “social counter-revolution to preserve both the wealth (and liberty) of the old regime, advancing the same neoliberal policies as those of Ben Ali.” Thus, according to Allinson’s approach, Tunisia never completed its revolutionary process.

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) February 5, 2023 |

It would be interesting to read the author’s analysis of the recent events in Tunisia. The book does not cover Tunisian President Kais Saied’s power grab in July 2021, when he assumed executive power and closed the Parliament.

He would later cement his authoritarian project with a constitutional referendum and a new parliamentary election boycotted by the opposition. Allinson was certainly mistaken in his assessment of Saied, as he writes in the book that his election “brought to power a figure more representative of 2011.”

Allinson finally compares two cases that emerged in the aftermath of the Arab Uprising and, despite presenting stark differences, have often been described as revolutionary.

These are the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava.

The author argues that ISIS was actually a counter-revolutionary project. The revolutionaries who had created alternative institutions in Syria after the uprising against al-Assad were either killed, detained, or forced into exile at the hands of ISIS.

The terrorist group, remarks Allinson, imposed a transformation that was “brutal, totalizing and partisan” but did not destroy the social relations or administrative structure of the old regime. Meanwhile, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the leading political force in North-Eastern Syria, introduced deep changes in the political structures —often to the exclusion of political rivals — as well as gender relations of the areas it controlled.

Nevertheless, “the PYD remained trapped within the relations of capital and state they aspired to abolish.” The autonomous administration “relied upon oil revenue and agricultural taxation to fund itself” and the salaries of the civil servants working in the area continue to be paid by the Assad regime.

Although those living under ISIS rule or the autonomous administration experienced profound changes in their lives, Allinson does not qualify these events as revolutions because the degree of political and socioeconomic change was not as all-encompassing as his approach to revolution would require. Although less strict understandings of the term “revolution” would yield different conclusions, Allinson must be commended for his consistency throughout the book.

The Age of Counter-Revolution’s greatest contribution is to be found in its proposal to approach the decade after the Arab Uprisings from a perspective that, although not new, undergoes an impressive development in Allinson’s work.

True, revolutions failed to materialize, but focusing on the revolutionaries’ shortcomings, although necessary, can at most help to explain half of the story. The countries that saw major popular mobilizations in 2011 would witness how different alliances involving national elites and non-elites as well as foreign countries turned back the clock of revolution in the years to come. Counter-revolution, to the detriment of the popular demands of 2011, managed to impose itself.

Marc Martorell Junyent is a graduate of International Relations and holds an MA in Comparative and Middle East Politics and Society from the University of Tübingen (Germany). He has been published in the London School of Economics Middle East Blog, Middle East Monitor, Inside Arabia, Responsible Statecraft and Global Policy.

Follow him on Twitter: @MarcMartorell3

![A youth holds up a sign depicting the crossed-out face of Libya's eastern military chief Khalifa Haftar with text in Arabic reading "Nooooo to the war criminal" as people take part in a parade in the coastal Libyan city of Tajura, east of the capital Tripoli [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2023-02/GettyImages-1238752479.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=skX1NwuJ)

![A Tunisian protester shouts slogans as he holds up a placard with a caricature of Tunisian President Kais Saied, during a demonstration held by supporters of Tunisian opposition parties and Tunisian civil society groups against Tunisian president Kais Saied [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2023-02/GettyImages-1242084145.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=tq4kCJ-6)

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News