What will happen to Afghanistan's national languages?

Pashtuns, Afghanistan's largest ethnic group and a sizeable minority group in Pakistan, have long represented the primary speakers of Pashto.

They also compose the majority of the Taliban, a group that Afghanistan's minorities have often associated with Pashtun nationalism even though the militants have tried to downplay this reputation.

Hazaras, Tajiks, and many other Afghan minorities speak Dari – the Afghan dialect of Persian – as a first or second language. Dari has long functioned as a lingua franca in Afghanistan, a status that Pashto has never achieved despite Pashtuns' numerical supremacy.

|

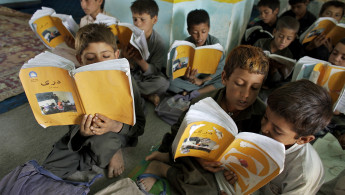

When the Taliban ruled most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, the militants imposed Pashto on non-Pashtuns, even rewriting Dari signs and textbooks |  |

When the Taliban ruled most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, the militants imposed Pashto on non-Pashtuns, even rewriting Dari signs and textbooks.

If peace talks bring the Taliban into the Afghan government, the militants will have the perfect platform to insist on returning Pashto to the preeminent role that it enjoyed under the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the Taliban's short-lived government. For now, however, many Afghans prefer Dari, a language intertwined with Afghan cultural heritage.

|

|

| Read also: Casualty of war: Deforestation and desertification in Afghanistan |

"Pashto and Persian are both official languages in Afghanistan, but they haven't been used evenly," said Dr Shah Mahmoud Hanifi, a professor of history at James Madison University and author of Connecting Histories in Afghanistan: Market Relations and State Formation on a Colonial Frontier.

"For example, while Pashtuns might have long dominated politics, on the whole Pashtun officials aren't intimately familiar with Pashto, often choosing to use Persian instead of the language associated with their claimed ethnicity. After all, Persian is a historical tool of states, governments, and bureaucracy."

Unlike Pashto, whose speakers have isolated themselves in the mountains of the Hindu Kush for much of their history, Persian's many dialects have had millennia to establish themselves in many corners of Central and Western Asia.

Since the reign of Cyrus the Great over two thousand years ago, a series of Persian dynasties have spread their language through expeditionary warfare and international trade.

The Sassanian Empire introduced Persian to the historical region that encompasses Afghanistan in the third century, bringing Persian literature to the remote lands of Central Asia.

"Persian is a spoken language, but it has a deep, rich textual presence," noted Hanifi. "Pashto is far less textualised in comparison. You might even say that it has long been resistant to textualisation. For most of its history, Pashto has been a predominantly spoken language in Afghanistan."

|

The wealth of Persian volumes on philosophy, science, and statecraft encouraged many of the region's inhabitants to adopt the language of their rulers |  |

The wealth of Persian volumes on philosophy, science, and statecraft encouraged many of the region's inhabitants to adopt the language of their rulers.

When Pashtun kings came to replace Persian emperors in Afghanistan in the eighteenth century, Dari retained its favoured status among the country's intelligentsia and ruling class. All the while, Pashto continued a trend of borrowing vocabulary from Dari as Afghanistan's Pashtun rulers officialised Persian as the language of their royal courts.

"Dari is modern Afghanistan's variety of Persian and a continuation of Classical Persian, which influenced written Pashto strongly from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century," said Dr Mikhail Pelevin, a professor of Iranian studies at Saint Petersburg State University and author of several books on Afghan literature.

"The mutual influence of modern Dari and Pashto is mostly limited to lexical borrowings."

Just as the Islamic conquest of Greater Iran filled Persian with Arabic loanwords, the Sassanian arrival in Afghanistan began centuries of Persian lending its own vocabulary to Pashto. In fact, the Arabic words found in Pashto today first resulted from Pashto taking Dari's own Arabic loanwords.

|

The Arabic words found in Pashto today first resulted from Pashto taking Dari's own Arabic loanwords |  |

"Persian has had and still has more impact on Pashto than Pashto on Persian," said Dr Mateusz Kłagisz, an assistant professor of Iranian studies at the Jagiellonian University and the author of a book on Persian orthography.

"Persian is a language of culture, literature, administration, diplomacy, and trade. Pashto is the language of a single ethnic group and has never had a social status like that of Persian. For centuries, Persian was a lingua franca detached from a specific ethnic group."

To a lesser extent, Pashto has had an impact on Dari, and, in recent years, Pashtun nationalists have attempted to popularise Dari's use of Pashto vocabulary. Even so, the relationship between Dari and Pashto remains lopsided, Pashto staying confined to Afghanistan and the Pakistani hinterland.

|

| Read also: 'Greening the desert': What drives militants' environmentalism? |

"Pashto's vocabulary has influenced Dari, especially in the southwest of the country and areas around Kabul," noted Dr Rahman Arman, a senior lecturer at Indiana University Bloomington and the author of several Dari textbooks.

"In the same locations, Dari has affected Pashto – but primarily in terms of sentence structure. That said, Pashto uses many Dari words, phrases, and structures."

The outsize role of Persian in Afghanistan's popular culture amplifies the influence of Dari there. Many Afghan leaders and intellectuals claim the Persian poets Ferdowsi and Rumi as national symbols, leading to a competition over Persian cultural heritage with Iran, the Persian Empire's ultimate successor state.

While Afghans also celebrate Pashtun historical figures such as Ahmad Shah Durrani, heralded as the founder of the Afghan nation-state, Durrani illustrated the overlap between Dari and Pashto: he wrote poems in both languages. Even among Pashtun elites, Dari has held wide-ranging appeal.

"Dari has been the official court language of the area encompassing Afghanistan since the Sassanian Empire, a trend that continued during the reign of the Pashtun kings," said Arman.

"Moreover, most scientific books, articles, and documents were written or translated into Dari before Pashto."

|

Most scientific books, articles, and documents were written or translated into Dari before Pashto |  |

Dari allowed Afghan rulers to interact with the rest of the world in a way that Pashto failed to match. The borders of the Qajar Empire, the last manifestation of the Persian Empire, extended from the Caucasus to the Gulf of Oman in the nineteenth century.

The Mughal Empire in India and the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia used Persian in their royal courts for the same reason that their Afghan counterparts did: like English, French, and Spanish today, Persian had become a world language.

"Persian offers a large vocabulary and structure that lends itself to statecraft," observed Hanifi, "and the Afghan state grew out of the ashes of the Mughal and Safavid Empires."

Dari's name derives from its popularity in the Persian Empire's royal courts, a hint of the prestige that Indian, Pashtun, and Turkish monarchies later associated with Persian. Pashtuns have long occupied positions of power in Afghanistan, yet Pashto has rarely threatened Dari's primacy in the country.

"Dari is a successor to an imperial, cosmopolitan language that had longtime literary traditions and always dominated the region," Pelevin told The New Arab.

"The state-building policies of Afghan rulers since the mid-eighteenth century have consistently promoted Dari, not Pashto, for reasons of expediency despite the fact that these rulers were of Pashtun descent."

Though Persian's role in the international community has diminished, little about the relationship between Afghanistan's official languages seems to have changed.

Nowadays, Pashtuns lament that Dari predominates in Afghan courts, government agencies, and universities at the expense of Pashto.

"Although both languages have been recognised as official in Afghanistan, they do not have the same political and cultural position in the country," added Kłagisz.

Outsiders might consider the rivalry between Dari and Pashto trivial in the context of the War in Afghanistan, yet these languages' evolving relationship speaks to wider tensions between Pashtuns and the country's minorities.

Dari's precedence notwithstanding, Pashtuns have controlled Afghanistan in one form or another for centuries. Afghanistan's current, Pashtun-led government has worked to incorporate minorities.

Nonetheless, many of them fear that a Taliban resurgence could see a return to the time when the militants massacred Hazaras, Tajiks, and Uzbeks who opposed the rule of the Islamic Emirate.

In light of Afghan minorities' concerns about ongoing peace talks between American and Taliban officials, Dari and Pashto's future in Afghanistan has found renewed significance for many.

"The Taliban has used Pashto during its insurgency to develop ties to Pashtun tribes," said Hanifi, "but this decision has limited its appeal among non-Pashtuns. If the Taliban returned to government today, there would be a shift in the relationship between Pashto and Persian.

"Pashto would be used more often in official documents, and the Afghan government might even opt to expand patronage of Pashto education. However, Persian would likely remain the dominant language of Afghan bureaucracy."

If the Taliban does decide to negotiate with the Afghan government, which the insurgents have so far avoided, a peace treaty could rebalance the relationship between Dari and Pashto.

Nonetheless, Dari seems likely to maintain its distinguished status in Afghan officialdom for many years to come.

"Afghanistan's leaders have changed, but they've remained a Persian-speaking lot for centuries," Hanifi told The New Arab. "Not even the Taliban seems likely to change that trend."

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture, and politics in Africa and Asia. He has conducted fieldwork in Bosnia, Indonesia, Iraq, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Oman, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda. His research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)