Nine years of reconciliation in Algeria brings rewards

Sheikh Ahmad bin Aisha was, fourteen years ago, hiding from the Algerian army in the country's rugged mountains. But the day came when the local commander of the Islamic Salvation Front climbed down the hillside, and handed over his rifle.

He rejected the armed struggle and returned home. He now lives now in the town of Chlef in northwestern Algeria, a decision he says he has no regrets about. Bin Aisha was among thousands of fighters who took up arms against the Algerian state in 1992, but following a reconciliation deal he was granted immunity, returned to his family and began civilian life all over again.

The mood of the Algerian people on both sides was exhausted from a decade-long civil war between Islamists and the military, and the rebels were welcomed back by people in villages across the country as peace returned.

The Algerian Civil War was a brutal conflict of attrition and butchery between a myriad of Islamist factions and the central government. It all followed a series of clashes during electioneering between the Islamic Salvation Front and the secular-leaning National Liberation Front in 1991.

Once it became clear that the Islamists would win the election, the army cancelled the second round of polling, and the conflict soon exploded into a full-blown guerilla war.

In a national referendum on 28 September 2005, 97 percent of Algerians approved the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation Law (PNRL) put forward by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, to formally end the war. It also granted legal status to 6,000 armed members of the Islamic Salvation Front (known by its French initials AIS) who had renounced violence in 1997. A further 9,000 rebels who surrendered to the government in 1999 were also included in the deal.

Path to peace

The PNRL set out a road map for settling the conflict, the most important points including amnesty for rebels who agreed to a ceasefire and surrendered their weapons, the release of prisoners involved in the war, and the government offering social assistance and compensation to more than 11,000 family members of the rebels who were killed by the army in the 1990s.

Nine years later and 15,000 repentant rebels have passed through this reconciliation programme and now face the challenges of daily life back in their towns and villages, rather than the hardships of life in the wilderness as a guerilla fighter. Algiers was relatively successful in reintegrating these former fighters back into public life - not an easy task for the authorities who were exhausted materially and morally by the war, with the country's infrastructure at the point of destruction.

After years of guerilla warfare, rebels returning to civilian life found it difficult to be among people that they had caused to suffer immensely, with the fabric of society ripped part from the vicious fighting.

Among those taking part in the programme were 2,200 members of armed groups and their supporting networks who were detained by the army and released during the implementation of the PNRL. More than 4,300 workers who were dismissed from their jobs after being accused of belonging to an armed group or providing them with financial support were re-employed.

Algerian authorities launched an initiative to create a spirit of reconciliation in the country - a national effort that sought to repair the damage the people had suffered, described by law as "the victims of the national tragedy".

| Nine years later and 15,000 repentant rebels have passed through this reconciliation programme. |

National tragedy

Nonetheless, the authorities tried to develop a legal framework that would close outstanding cases pertaining to the civil war.

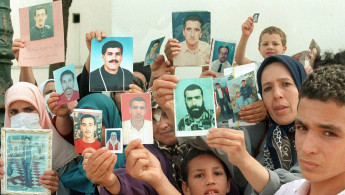

One of the prominent issues remains the thousands of people who went missing during the conflict, largely considered to be "disappeared by the army". The authorities have acknowledged a list of 7,500 missing persons. As part of a settlement regarding their cases, the authorities paid financial compensation to their families and issued death certificates for the deceased.

Many families, however, are still refusing any legal, political or financial settlement before they know the fate of their relatives and the conditions and circumstances behind their kidnapping and probable assassination. Their families insist that the Algerian security services were behind their disappearance and the mothers and families of missing people continue to hold weekly public gatherings in Algiers city centre every Wednesday.

Another outstanding issue is to finally get to grips with providing a legal status for "the children of the mountains" - infants born in the rebes' mountain bases. Many rebels brought their wives to the stations. Other women were kidnapped from their villages and married to the fighters by force.

"The authorities counted 500 children who were born on the mountains and were not registered with the civil status authorities," said Marwan Azzi, head of the judicial aid unit charged with implementing the PNRL.

"Some of their fathers were killed in fighting against the army, a fact which makes it difficult to confirm their legal status in civil records. With difficulty, the authorities did settle the status of 37 of them, as well as the status of the women who were raped by the rebels."

Reviewing the past

However, a review of reasons for how and why the conflict started has not yet begun. The Islamic Salvation Front is still outlawed and its leadership banned from political activities or standing as candidates in elections. Revoking this ban is strong demand by the cadres of the outlawed party.

It is true that the national reconciliation programme has placed Algeria on a new road, from being a terror-exporting country shattered by instability to a more confident nation spreading its experiences in national reconciliation to other war torn countries, such as Mali and Libya.

However, as much as the project has contributed to security and stability in the country, it still needs time to run its course and to tackle several thorny social and economic issues that could lead to further internal disturbances.

This article is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News