Why Muslim countries are turning their back on China's repressed Uighurs

Addressed to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, the letter from mostly Western nations is urging Beijing to end repression in Xinjiang and allow UN experts to visit the region.

Significantly, this is the first collective international move against China's domestic policy.

Michelle Bachelet requested the Chinese authorities for permission to undertake a fact-finding mission in Xinjiang region, and her office stressed that access would be required to key sites, in addition to the 'vocational education centres'.

|

This is the first collective international move against China's domestic policy |  |

Surprisingly, just a few days later, 37 mostly Asian and African countries responded with a letter to the United Nations praising China's human rights record.

"Faced with the grave challenge of terrorism and extremism, China has undertaken a series of counter-terrorism and deradicalisation measures in Xinjiang, including setting up vocational education and training centres," it read.

According to this document, no terrorist attacks have taken place in the previously troubled region since the last three years due to China's effective measures for counter-terrorism and de-radicalisation.

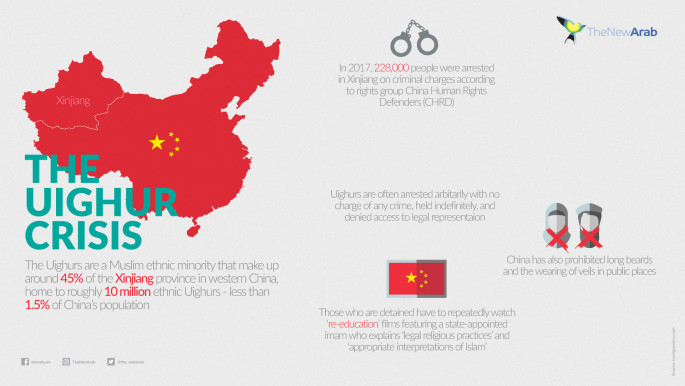

However, the situation on the ground may be tense, and responsible estimates shared by the Human Rights Watch state that nearly 13 million ethnic Uighurs remain in detention, while over one million are being held in "political education" camps. In addition, there is a general heightened surveillance of Muslims in the entire region.

|

|

|

There is a general heightened surveillance of Muslims in the entire region |  |

Unusually, most of the signatories of the second letter defending China's new policy to the UN happened to be Muslim countries like Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Qatar, UAE and Syria.

In the past, as Organization of Islamic Co-operation (OIC) members, these countries had demanded justice for Rohingya Muslims in line with the forum's mandate to "safeguard the rights, dignity, and religious and cultural identity" of Muslim minorities.

Where Xinjiang is concerned, these OIC delegates are satisfied as they had been taken on a tour by Chinese government officials.

However, some other OIC members such as Afghanistan, Albania, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey abstained from signing the statement in support of Beijing.

Nevertheless, all Muslim majority countries have ignored the call by the UN Human Rights Council to investigate the situation in Xinjiang.

Having common ethnic links with Turkey, the eight million Uighurs, Kazaks and Kyrgyz population in Xinjiang happens to be the fourth largest concentration of Turkic people globally while Turkey itself has around 53.6 million Turks.

In the past, Uighurs have even demanded sanctuary in Turkey. Out of all the Muslim countries, Turkey had initially taken up the Uighur matter last year.

But after his recent trip to Beijing, Turkish President Erdogan also expressed his satisfaction over the situation in Xinjiang.

Ostensibly, Beijing managed to allay Ankara's concerns and convinced Erdogan that Muslims faced no discrimination as minorities in Communist China.

Keeping in mind the rampant reports in media regarding China's Xinjiang crisis, the matter deserves a more empathetic approach. Like Erdogan had said after meeting with the Chinese President, it may be possible to "find a solution to this issue that takes into consideration the sensitivities on both sides."

Maybe, more Muslim-majority countries would like to help in ending the controversy. But certain factors make them stay at a distance.

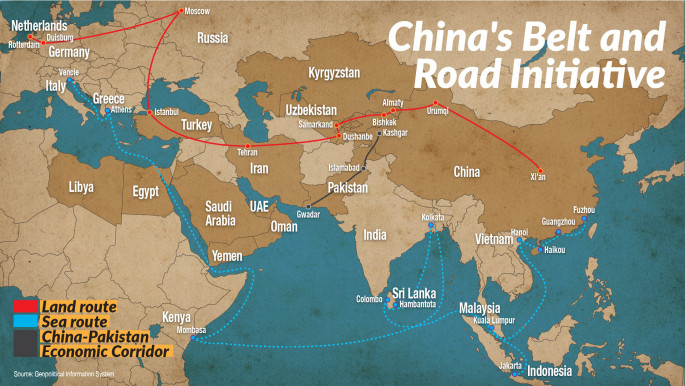

For starters, quite a few OIC members are part of China's mega-project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Where business interests are concerned, these Muslim countries have their economic future tied up with China, the second global superpower.

|

|

The political and practical cost of probing into the Uighur issue would be too high for any of these countries to withstand.

Secondly, even otherwise, Muslim solidarity on other issues has often come into question. Be it Syria, Yemen or even the ongoing frictions between the US and Iran; the Muslim world has always come up with a scattered response or just divided itself into two separate lobbies.

Thirdly, while China's energy security depends on the GCC countries which are its main suppliers of hydrocarbons, Beijing remains the Arab world's secure long-term consumer base for the next few decades as fluctuating oil prices and the Western demand for alternate energy sources disturbs its economic stability.

|

|

| Read also: Welcome to Kashgar! Where you can sip tea and watch Uighurs be persecuted |

Lastly, Xinjiang is China's border province and the success of the BRI depends on this region as it is the main land route to the Arabian Sea via Pakistan.

Any instability here can hinder Beijing's plans for trade connectivity, endanger its investments and disturb all stakeholders.

But ignoring the problem is not the best solution.

According to a research study conducted by Graham Fuller from the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, " If the "Xinjiang problem is not resolved, it is bound to affect not only broader developments within the People's Republic of China but also the stability of Xinjiang's neighbours in Central and South Asia and, indeed of the broader world order."

But why did the problem begin and how will it end?

According to Fuller's research, over the last two decades, China's Western border province of Xinjiang underwent rapid economic development, enough to boost its per capita income to the 12th among all the 31 provinces.

Ranking third in the equity of income between its rural and urban populations in the whole of China, the region also has ample oil and gas reserves. Not only that, even the literacy and school completion rate is above the national average.

Even tourism increased by 75 percent in 2018.

Apparently, Beijing started expansive development programs worth around $7 billion to further integrate Xinjiang.

Spurring up economic activity, this boosted migration from other provinces, which in turn irked the local Muslim multi-ethnic population.

Consequently, around one decade ago, conflict broke out in Xinjiang after a workplace riot that resulted in the death of two Uighurs.

Riots took place after a police crackdown and ever since then the region has faced security and terrorism issues.

It was in 2017 that the first reports about 'detention centres' surfaced in the news and after these were mentioned in the UN report in 2018, China legalised them as training centres.

Sabena Siddiqui is a foreign affairs journalist, lawyer and geopolitical analyst specialising in modern China, the Belt and Road Initiative, Middle East and South Asia.

Follow her on Twitter: @sabena_siddiqi