Missed part one of Otman Aitlkaboud's study? Catch up with Jewish Arabs and the birth of Israel's Black Panthers

Otman Aitlkaboud is an Executive Committee member of the Arab-Jewish Forum working on improving relationships between Arabs and Jews in the UK and beyond. He formerly worked at conflict resolution think tank Next Century Foundation and for the European Union External Action service in Armenia. Follow him on Twitter:@OtmanA

The legacy of Israel's Black Panthers

A significant number of politicians believed that the actions of the Panthers were part of a passing revolutionary phase that followed the numerous global revolutionary turning points in 1968 surrounding the huge escalations of the Vietnam War.

But the protesters in Israel believed their actions reflected deeper concerns within the Mizrahi community. Having felt they missed out on being pioneers before 1948, and finally "proved themselves" in Israel's 1967 Six Day War, they resented all the more their continued marginalisation, watching on as new Ashkenazi arrivals immediately received preferential treatment.

Elie Eliachar, in his posthumously-published English translation Living with Jews, writes about Eastern European/Ashkenazi prejudice and how it kept Mizrahim from pursuing posts in government.

"This phenomenon - the exclusion of Sephardim [an ethnic lineage closely identified with Mizrahim] from decision-making levels - became particularly conspicuous in the process of building a civic bureaucracy after independence," he writes.

"Despite the fact that Sephardim had comprised the great majority in the Mandate civil service, the new government offices were staffed almost entirely without them. Not one Sephardi was found in any position of influence in the political, economic or cultural ministries. The new law courts too were established on a political basis. No Sephardi judges were appointed to the Supreme Court, and only a few of the distinguished group of Sephardi judges from Mandate times were given posts in the lower courts."

The state did not accept that the protests were largely down to the social malaise that the Mizrahi community continued to experience. Even so, the Panthers were briefly successful in encouraging a government commission of inquiry which concluded that Mizrahim had indeed been discriminated against at many levels of society.

The commission had made recommendations to increase budgetary resources, but much of these new budget allocations were subsequently redirected to the security budget following the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

The prevailing establishment in Israel was Labor Zionist - but the Panthers held a mirror up to the Labor "socialists" with their demands for real social change and confrontation with the establishment. In short, the Panthers suggested that Laborites were not as progressive as they had thought.

|

The historic Likud victory that year was largely attributed to Begin's success in courting the sizable Mizrahim vote |  |

The activities of the Black Panthers eventually petered out, due to internal rifts and the trend of most Mizrahi groups following mainstream political parties.

Israel's 1967 War saw a shift in Mizrahim voting patterns, with many increasingly deciding to vote for the right-wing Likud bloc after the Labor government began to divert money into the Occupied Territories of the West Bank and Gaza - previously under Jordanian and Egyptian control from 1948 - 1967 - and away from the type of development towns largely populated by the Mizrahim.

|

|

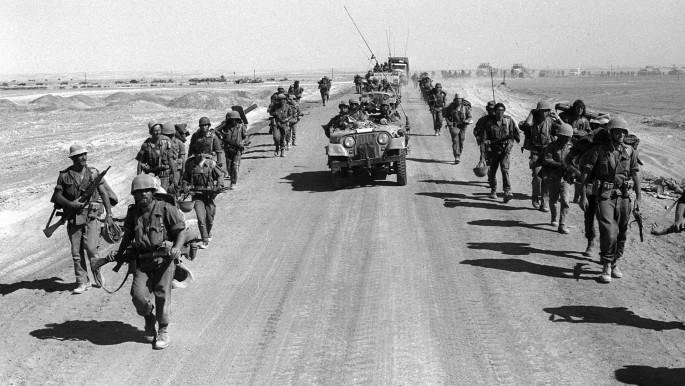

| The 1973 war diverted funding away from Mizrahi communities [Getty] |

Ironically, Israeli settlement of the

Begin acknowledged and spoke of the discrimination that they experienced under the Labor government, and many Mizrahim believed him sincere.

Mainstream left-wing movements in

Absent from even its mainstream grassroots organisations was a working class Mizrahim cadre, with the dominant milieu of the left from top to bottom being predominantly Ashkenazi, bourgeois, urban, secular and well-educated.

Mizrahim felt uneasy in Ashkenazi-dominated movements such as Peace Now, ironically sensing that peaceniks discriminated against them while at the same time backing Arab and Palestinian rights.

Instead, a conservative majority of Mizrahim found a home in Likud, or later, in the Sephardi religious party, Shas. Other more progressive Mizrahim - albeit fewer in number - gravitated towards Mizrahi-dominated movements like Keshet, the Mizrahi leftist Rainbow movement, and Shalom le-Mizrah, Peace for the East[erners] - which echoed the goals of Peace Now and Gush Shalom, but in Mizrahi terms.

Reuven Avergil's own political journey, having co-founded the Israeli Black Panthers, continued on the fringes of Israeli politics after serving for many years as a Knesset Member for the Communist Hadash party.

He currently heads the Tarabut-Hit'habrut Arab-Jewish movement for social and political change. Notably both in Hadash and in Tarabut, Reuven fuses the Mizrahi struggle with Arab causes.

|

The Israeli Black Panthers exposed policies that left the Mizrahim feeling excluded in politics, education, employment and more |  |

The Israeli Black Panthers did initially play a sizable part in contributing to a voice for a Mizrahi political consciousness. It successfully influenced the national debate during the 1970s and, paradoxically, the movement could claim credit for contributing to Likud's historic success in 1977 by bringing the issues of the Mizrahim to the fore - allowing Likud to position itself as the voice of the marginalised.

The Israeli Black Panthers exposed policies that left the Mizrahim feeling excluded in politics, education, employment and more. These issues even resonated with the Mizrahim who never supported the Panthers' entire radical political stance, opening up the political space for newer parties to lay claim to Mizrahi representation.

The mid-1980s saw the arrival of a new rival to challenge Likud for the Mizrahi vote that was now comfortably on the political right. The Shas party, with its Sephardi- and Mizrahi-dominated leadership, fused Mizrahi social concerns with ethnic pride and religious orthodoxy.

It championed the theological tradition of Maimonides and Yosef Karo and Baba Sali and the Babylonian Talmud - which once bore tremendous authority throughout the Jewish world, and still informed the Ashkenazi yeshivot (rabbinic seminaries). Headed by a former Sephardi chief rabbi, the Shas party has since offered an alternative for Mizrahi voters whenever they felt that Likud - and its recent offshoot Kadima - reneged on its promises.

Likud, by and large, still enjoys considerable support from the Mizrahim, but has never had a Mizrahi as its leader.

Paradoxically, Labor has had two: Binyamin Fuad Ben-Eliezer who was born in Iraqi Kurdistan, and Amir Peretz who was born in

Mizrahim have occupied other senior posts including one foreign minister (David Levy), two presidents (Yitzhak Navon and Moshe Katsav) and the military's chief of staff at the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur war (David "Dado" Elazar).

Improved socioeconomic conditions played a significant part in this course too; but that is not to say that the legacy of Wadi Salib and that of the Israeli Black Panthers is no longer relevant today.

Protests against police brutality by Arab citizens of Israel in October 2000, and last year by Israel's Ethiopian Jewish community along with Israel's social justice protests of 2011, proved not only that issues to do with discrimination, adequate access to housing and the eradication of poverty were still applicable - but, as in the case of the social justice protests, it also confirmed the bitter divisions within the left between Mizrahim and Ashkenazi bourgeois - differences that eventually helped bring the 2011 protests to an end.