Inside Douma: A desperate portrait of life in Syria

Protests come in difference shapes and sizes; the intensity of the action often being directly related to the scale of the torment suffered.

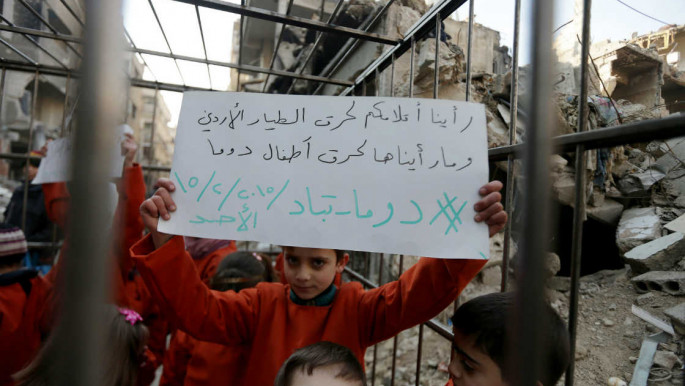

And so it is that here in Douma market, 15 kilometres north of Syria's capital, Damascus, a group of 15 young children - some only toddlers - were part of a chilling protest. Dressed in tattered orange jumpsuits - like those in which the Islamic State group clothe their execution victims - they were ushered into a crowded cage, like squawking chickens awaiting slaughter, before raising banners that read "Stop the killing of children".

Once the cage door was bolted, Jaysh al-Islam activist Houmam Sayid pretended to set the cage on fire using a flaming torch, mimicking the murder of Flight Lieutenant Moaz al-Kasasbeh - the Jordanian pilot who was caged and burned alive by IS in December 2014.

The controversial stunt, held in February 2015, called for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's atrocities during Syria's bloody civil war to be compared with those carried out by jihadists.

"We wanted to show the world how the Assad regime is unashamedly and indiscriminately murdering children," Sayid tells The New Arab in a secluded security hut near Tawheed Mosque. He is surrounded by four gun-wielding footsoldiers who hang on his every word, and seem itching to pull the trigger upon his command.

|

|

| 'We saw you writing when [Kasasbeh] was burned, but we did not see you writing when the children of Douma burned' [Photo: With permission] |

"The young heroes we picked were actors and never in danger. Their parents felt proud to watch them illustrate the truth.

"I was also honoured to hold the flame. It felt like being the torch-bearer at an Olympic Games, but I must admit it was difficult to keep my hand steady. It is traumatic to imagine setting a human being on fire, especially an innocent child."

When pressed whether it was abhorrent to use innocent children in such a sickening capacity, Sayid abruptly ends the interview and storms off muttering Arabic profanities.

Those involved, who have grown up knowing nothing but war, may have been too young to know what they were imitating - but this hardly excuses cramming children into captivity for over an hour just to make a political point, however powerful.

Douma, the caged city

Two years on and rebel-held Douma still feels very much like a locked cage.

The government staunchly prevents most outsiders from entering, and stops residents fleeing to Damascus and its surrounding suburbs.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

The blockades became extra stringent after August 16, 2015.

Six months after that hellish demonstration, the Syrian Air Force launched vicious airstrikes on both Douma and neighbouring Harasta - two of the most densely populated cities in eastern Ghouta.

"First there was a massive explosion in the el-Hal market," explains an emotional Abood al-Diri. His 22-year-old wife Maya was killed in the blast. She was seven months pregnant.

Loss is such a universal language that Abood's pain is palpable, even before receiving translation.

"Next, as paramedics and aid workers gathered to treat the injured there were more shellings. Once things calmed down, all that was left were people screaming for help and corpses covered in blood, rubble - even fruit and vegetables. The noise was slowly replaced by an unwelcome silence. How we wished for more crying, because at least that meant someone's loved one was still fighting for their life.

"I just kept calling out Maya's name and when I didn't hear back I knew she was gone. It took us almost 24 hours to find her body. She was seven months pregnant with our first child.

"All she wanted was some qamar al-din [dried apricots]. They are quite hard to find at the moment but when possible I eat one each day in her and my unborn daughter's memory. I called her Maya as well."

| More than 100 people were killed in the Douma Massacre, when Assad's aircraft targeted the local market on August 16, 2015 [AFP] |

The government's stated target for what became known as the Douma Massacre was the Jaysh al-Islam headquarters, but US-funded rescue operator Syrian Civil Defence - known colloquially as the White Helmets - maintain at least half of the 100-plus fatalities were under the age of 21.

A journey to two mass graves, where 60 of the victims are buried backs up this claim.

|

|

| The corpses of those killed in the Douma Massacre overwhelmed local hospital morgues [AFP] |

Upon arrival it is instantly apparent that Douma has run out of space for its dead.

Even though gravediggers hurriedly constructed a new terraced cemetery in November 2015, individual plots are a rarity, especially for the poor.

Not all of the deceased are officially known, since some of the corpses were too deformed to be formally identified, but mourners who visit the site from Douma's once cozy, close-knit community say they know precisely who perished.

"Five years ago we were such a happy city," sighs 36-year-old grocer Mohammed Fathi. His 12-year-old daughter Sara was partially blinded in the massacre.

|

Two of Sara's friends are buried here. They died during a game of hide and seek with her, and I can promise you they were laughing until their very last breath |  |

"We were such a vibrant city, but so many young faces have left us. Douma now has a cloud of depression hanging permanently over it.

"Two of Sara's friends are buried here. They died during a game of hide and seek with her, and I can promise you they were laughing until their very last breath. I take comfort in that. They are playing in heaven now, I am sure of this."

Douma has never truly recovered from one of the civil war's most devastating attacks - and peace hardly looks to be around the corner.

The market continues to be periodically shelled, and with more ghosts than living residents, there's a strong suggestion the bombardment is intended to destroy supplies rather than directly target insurgents.

The carnage hasn't just caused physical casualties, but left Douma with a depleted population of around 70,000 - 41,000 fewer than the figure listed in the 2004 census.

The International Committee of the Red Cross estimates as many as 2,000 of those still living here are amputees - that's one in 35 of the town's residents - with most struggling to find wound dressings, crutches or wheelchairs.

"Losing an arm or leg is life-changing, and without proper support and resources it can feel impossible to handle," admits 23-year-old Satra resident Abu Ahmad.

He was working as a tailor until August 2013, when some stray shrapnel left him paralysed from the waist down.

"Douma can't handle the current volume of amputations. Even if the affected limb is successfully removed that's just the beginning of the journey," says Abu Ahmad. "Infection is commonplace and there is nowhere appropriate to rest and recuperate. Wheelchairs also aren't easy to find and, as importantly, there aren't enough trained psychologists available."

|

|

| The wheelchair race was started with pre-Baath opposition flags [WAFA] |

|

| _ | |

_ |

|

| The race was organised to build friendship and solidarity between the city's many amputees, and to overcome a stigma often attached to becoming permanently injured [WAFA] |

|

Abu Ahmed now works for the Wafa Association - a non-governmental organisation specifically founded to care for the disabled - and in his new role organised a small, yet spirited, wheelchair race through the streets of Douma to coincide with the start of the Paralympics in Brazil's capital Rio de Janeiro last September.

"Only 12 of us took part, but it wasn't about the numbers,” says Abu Ahmed, who plans to stage a second race later this year.

"The idea was to send a message: to show amputees they don't have to die from depression. Emotional support is here and with a little luck, physical aid will follow. All Douma residents, not just us [amputees], pray for this to arrive every single day."

Douma's false dawn

There was fleeting optimism on 10 June last year, when humanitarian groups were finally granted entry to Douma for the first time in three years. But the safe and unhindered access they requested never fully materialised and that, in turn, stopped those aid deliveries that did successfully pass through checkpoints from reaching the neediest recipients.

A few new field hospitals were nonetheless opened in the rubble-strewn basements of safe houses.

The Unified Medical Office in Douma oversees such facilities and endeavours to fill them with rudimentary locally sourced medical equipment - but supplies are extremely short.

"We lack qualified medical staff - and recruiting from outside Douma is problematic," says the animated Dr Muwwafaq Saada.

Three medical students from the University of Damascus tell me they begged to volunteer in Douma but couldn't get the necessary government approvals, so ended up painting murals of solidarity on their campus walls.

|

|

| Medical students at Damascus University painted murals in solidarity with Douma |

"It is also very difficult to maintain a basic standard of hygiene," Dr Muwwafaq continues.

"We had to shut Douma's only dialysis clinic last year because it was impossible to run with the thin supplies and failing equipment at our disposal. That was effectively a death sentence for the 18 patients inside at the time, but keeping it open wouldn't have saved them, just [spent] the limited resources we had left.

"Another big problem is that Douma lacks specialists and we can't refer patients to Damascus. My dear friend Dr Nabil Daas, for example, was shot in the back of the head at his home [last May]. He was our only gynaecologist.

"Women here dread their periods. There is a shortage of sanitary pads and they are expensive. Many reuse old ones leading to fungal infections or kidney pain, and when this happens they often don't seek help - because they fear talking openly about such problems.

"Those of us still working are exhausted and our hands are tied unless more medical aid arrives. There is some suggestion it is being intentionally confiscated [by the government] in order to ensure a rebel-held city like Douma remains weak. The result is helpless doctors, suffering patients and hospitals that are starting to feel like morgues."

To even term these underground healing stations "hospitals" is a stretch.

If the one near the Mahmood Mosque is representative, then only the seriously sick are guaranteed a bed - the majority of which lack pillows. Patients with minor wounds must perch on a wobbly table as they are sewn up, while those having broken bones wrapped in casts or slings lie upon the cold, hard, non-sterile floor.

|

|

| Douma's field hospitals are full beyond capacity. Many of the injured have to be treated upon the floor [NurPhoto] |

The wall is stained with spatterings of blood and even a small handprint - perhaps from a suffering child who leaned against it for support. Helpless parents also kneel in front of it, praying for miracles.

The narrow corridor leading to the ward is extremely noisy. It echoes with piercing screams from the injured. These can be heard above ground, too. But once inside, when the scalpels are put away, there is an eerie silence - a tangible and terrifying unspoken acceptance from those admitted that this will potentially be the last place they'll see.

Water is a weapon of war

An alarming number of those fortunate enough to dodge hospital are still at risk of death via starvation or dehydration. This is due to the paucity of both food and clean water in Douma.

| | |

| Watch: Archive video shows the result of the 2013 chemical attack in Douma [Warning: Graphic footage] |

Since August 2013 - when shells filled with poisonous gas rained down on the city - most of the population have been forced to eat just one meal per day.

Things have moderately improved since last June with fruit, bread and eggs more readily available. Other produce is expertly smuggled in from Damascus through tunnels. But just because food is on sale doesn't mean its extortionate prices can be met.

A loaf of bread (and a stale one at that) costs 450 Syrian pounds ($2) in Douma. That's almost five times pricier than in Syria's capital, a few miles away.

The Central Bureau of Statistics reports the average Douma family of four require at least 16,000 Syrian pounds ($75) per month to sustain themselves - meaning most breadwinners spend their entire pay cheque just to feed their loved ones.

Those without jobs - and unemployment is unsurprisingly rife across all of Syria - have no choice but to beg. Famished fathers are even instructing their sons to steal snacks, despite knowing that Assad's judicial system would likely send them to prison or forced labour if caught.

Like most other thirsty suburbs, Douma's lack of clean water is an equally grave issue. The supply chain to the Wadi Barada and Ain al-Fija springs - which serve 70 percent of the population in and around Damascus - was cut off in early January after infrastructure was damaged in fierce clashes.

The rebels accused the government of intentionally destroying water-pumping stations as part of a tactic to reclaim the land surrounding them - a feat achieved on 29 January. The government responded with allegations that the rebels poisoned both springs with diesel.

|

|

| Douma's gravediggers have had to build terraced plots, but even so, a single-occupancy grave is rare [AFP] |

Whoever is to blame, it is clear that water is being used as a weapon of war.

That's why the latest adage - or perhaps legitimate prayer - doing the rounds in Damascus is, "May the gold you hold become water."

Visitors to Syria are advised to bring in their own bottled water, but it tends to be confiscated at the Masnaa border if crossing over from Lebanon. Once inside Damascus, imported water is indeed like gold dust, and only readily available from luxury establishments like the opulent Four Seasons - one of the few hotels still taking advanced bookings with rooms starting from $360 per night.

A bottle of Evian is even more expensive here than anywhere else in town.

On the southern tip of Douma, in the village of Mesraba, I gift a large bottle, purchased for $18, to 14-year-old Noora al-Masri. She can't quite believe her luck or hide her infectious smile. Noora carefully takes just the slightest of sips, artfully curling her tongue around the underside of the cap, preferring to lick that dry rather than enjoy a proper swig from the bottle.

She then seals it tightly shut and sprints off to offer her friends a taste of what has become a rare delicacy.

"This is the first clean water I have seen in a long time," says the noticeably panting Noora upon her return. She's worked up a whole new thirst through all the running. "You get used to not drinking it. We squeeze fruit to make juices and keep buckets of dirty water to bathe in. It isn't easy. I feel scared some days but I am pleased to be alive."

Civil war inevitably cuts childhoods short, and Noora is mature for her age. Since January 2016 she has been forced to grow up quickly, losing her father, Mohammed, in a ruthless Russian missile assault on Mesraba that also left the brave teenager with a prominent scar on her right cheek.

"It doesn't hurt anymore," divulges Noora, pointing proudly at her war wound. She is now cradling her water bottle like a newborn baby, conscious not to spill a single drop. "I actually like it because I got it protecting my brother Sami from the rockets. He was only six, but now he's the man of the house. He has my father's eyes.

"I don't remember too much, except the whole city just vibrating like an earthquake. One of the walls in our home fell down. I just lay on top of Sami and a glass window broke above me. Some of the falling pieces cut my face."

Douma's secret abortion clinic

Noora's aunt Yara [a name which means "water queen"] is a nurse, and was able to expertly tend to her wound, but this would prove one of the last times she ever saw her niece.

A heartbreaking family feud over abortion was about to divide her family.

The 28-year-old Yara, who asked us not to publish her surname due to safety concerns, was two months pregnant with her first child when she discovered her husband Firas had been left in intensive care by the same Mesraba attack that killed Noora's father, Mohammed.

Firas would sadly pass away six days later, leaving his grieving widow too distraught to give birth without him.

|

I suppose she thinks I am a murderer... But I sat with Firas on his deathbed, and I think he understood I couldn't handle being a mother alone |  |

"Most of my family wanted me to raise the child in Firas' honour," Yara tells me in her modest home on the outskirts of Douma. There are tears in her eyes and she is nervous about speaking so candidly.

"My sister [in-law] was sure that's what her brother wanted and hasn't talked to me, or let me see my niece, since she found out I had an abortion. I suppose she thinks I am a murderer. I'm like the black sheep in the white herd. But I sat with Firas on his deathbed, and I think he understood I couldn't handle being a mother alone.

"He wished to take our son with him to heaven."

Abortion is illegal in Syria unless undertaken to save the life of the mother. Termination due to rape, or to protect physical or mental health is not permitted. If prosecuted, Yara could face up to three years in jail and the doctor who carried out her procedure would also be put behind bars.

After speaking to other medical professionals and some female friends, Yara realised there were other women looking to terminate their pregnancies - so set about using her connections to found a covert abortion clinic.

The facility opened in April last year and is housed within a makeshift pediatric centre.

Yara is rightly reticent to reveal the precise location, but coyly confirms it operates out of a cellar in a residence owned by a doctor. He is apparently well-known by some high-ranking rebels, who seemingly turn a blind eye. Yara refuses to confirm or deny allegations of rapes leading to pregnancies that fighters wish to make quietly disappear. The look on her face is telling, however.

|

|

| Catch up with all our special coverage on the fall of Aleppo |

"The hardest part was finding an obstetrician willing to take on the risk," she says.

"Sourcing supplies was a bit easier because even though we are separate from the children's hospital, we still share some resources.

"Every day I am terrified we will be shut down, but I can't let this [fear] show. To begin with, I didn't dare tell anyone what I was doing, but as time passed I wanted to reach out to more pregnant women. This is also why I am glad to talk to you. Women in Douma must know abortion is an option - and I still think lots of them don't."

Yara declined to reveal the exact methods used to terminate pregnancies. The World Health Organisation estimate 20 million unsafe abortions occur each year, mostly in "third-world countries", or places where termination is illegal.

One of the safest and most common methods is to employ suction to remove uterine contents through the cervix.

But the worry is that, due to lack of resources, Yara's clinic might be using the "coat-hanger" technique, where the womb's amniotic sac is broken with a sharp object. This can lead to infection and organ damage. Ingesting large quantities of plant poison, chili peppers or even vitamin C is another way to induce a miscarriage - yet all these methods are extremely dangerous, potentially sending the woman into toxic shock.

"We are as safe as we can possibly be and have a high success rate," Yara assures me. She won't be drawn on whether any of her patients have died, but nods silently when asked if the number of women treated in the past 12 months exceeds 100.

|

|

| Our most in-depth stories |

"Our biggest challenge is maintaining post-abortion care. We struggle to get hold of contraception as well. Plenty of my patients want to maintain a healthy sex life with their husbands, but are frightened about getting pregnant again.

"There is also very little we can do for patients in the more advanced stages of pregnancy. I am afraid we are not properly equipped to offer dilation and evacuation or hysterectomy abortions and it is very hard to turn desperate women away."

It is not difficult to find empathy with the women Yara's clinic treats. Some have lost their husbands or even entire families; many others have been sexually abused. Whatever the circumstances, Yara hears woman after woman tell her how the prospect of bringing a child into a heated civil war that has no apparent sight of ending is not just overwhelming but irresponsible.

"What if Douma becomes the next Aleppo?" asks Yara, who still hopes to reconcile with her sister. "We aren't far off and mothers don't want to bring children into that environment, especially those with children already. I suppose they have seen what it does to them.

"I understand some people think abortion is murder, but if that's the case then we are killing out of kindness.

"I think you have to live in Douma to realise a child should not be raised here - at least not without two strong, healthy parents. You must also remember that adoption, like abortion, is illegal in Syria. If children could be taken in by loving families abroad, there would perhaps be no need for my clinic."

Yara also hints that she hasn't only been approached by pregnant women.

|

Of course I sympathise with those who feel the only way to take away the pain of their sons or daughters is to send them to paradise |  |

A small but steadily increasing number of parents drop by each month to enquire about - and often plead for - assisted suicide on behalf of their severely wounded children. To date all requests have been refused, but the fact they were even made illustrates the acute distress felt by many of Douma's parents.

"Of course I sympathise with those who feel the only way to take away the pain of their sons or daughters is to send them to paradise," concedes Yara. "But even if we had the means to help them pass away peacefully this is not something I would feel comfortable doing... There is no way of knowing with certainty that [assisted] suicide is what the child really wants."

|

| Douma continues to be targeted by Assad's air force and its allies [AFP] |

What hope remains?

Yara argues that things will get worse, much worse, with continuing regime attacks leaving Douma a childless city. However, if and when the time comes, the Assad regime may try to reclaim the city very differently to its onslaught against Aleppo.

Analysts maintain a negotiated settlement is just as likely as a military offensive. January's peace talks between the Syrian government and various rebel factions in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana didn't explicitly confirm this, though, and humanitarian groups continue to raise valid concerns that Douma's tunnels - the only viable means of smuggling essential goods - could soon be sealed off.

Whatever happens next, the resolve of Syria's younger generations shouldn't be underestimated or discounted. Yara's pessimism is understandable, but Douma's children are not just vulnerable targets. They offer the hope of positive change - and if long-term peace is to be achieved they will ultimately be the ones to sustain it.

With this in mind, 40-year-old painter Abu Ali al-Bitar scavenges for rocket debris.

He transforms the former missiles into playground swings, so children here have something other than death to associate with weapon fragments.

"My neighbours thought I was mad," chortles Abu Ali. "I just came out of my shop one day with a rocket-swing."

|

| Abu Ali's 'Rocket Swings' use a weapon of war to put a smile on children's faces [Sameer al-Doumy] |

|

"That's how it all started. I took something that used to kill and turned it into a toy that makes children smile. I tell the younger ones, who don't fully understand what’s going on, not to dread the attacks. If they ask me what all the noise and smoke is I always say 'don't panic, it's just Allah giving you something new to play with'."

Hassan Majeed often frequents Abu Ali's novel swings. The seven-year-old lost his right arm last February in an airstrike that left clouds of yellow smoke lingering for days.

Despite his injury, the delightfully hyperactive Hassan remains utterly convinced he'll one day turn out for Syria's national football team, though not in time for their potential appearance at the 2018 World Cup in Russia. His doting dad, Hayyan, says instead of being traumatised by the sound of attacks his son waits for the calm, then gleefully runs outside to sift through the wreckage in order to find objects he can use as an ersatz ball.

The danger posed by unexploded ordinance is huge, but does nothing to dampen the spirits of the football-mad youngster. Six of his seven years have been dominated by this war.

"Hassan won't play for Syria, but he can inspire our nation," reasons father-of-four Hayyan. "He has such a big heart. I dream of him meeting Cristiano Ronaldo. I am always telling him stories about Real Madrid because when I was younger I wanted to play for them."

Douma may appear a dire place at the moment but it is teeming with Syrian spirit. To keep the flame of hope alive, though, outside backing is urgently required.

It is crucial to understand that those trapped in Douma or any other part of Syria - plus the 4.8 million refugees in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey - are the victims of terror, not its perpetrators.

Contrary to the convictions of United States President Donald Trump, the vast majority are not security threats - or "bad dudes" as he recently dubbed them on Twitter. Furthermore, Trump's indefinite ban on Syrians entering America exposes a profound misunderstanding and mistrust of why those fleeing so urgently need help.

There is always a danger that a tiny percentage could be susceptible to brainwashing by organisations such as the Islamic State group, but there is surely less chance of refugees swallowing IS rhetoric about the evils of America if desperate Syrians are offered safety and an elevated quality of life by a global superpower such as the United States.

There is no doubt Syrians - 14 percent of whom are Christian or Druze - are being scapegoated due to brazen Islamophobia. According to research by California-based author Richard Todd, significantly more Americans are killed each year by armed toddlers (21 a year, averaged over ten years), lightning (31), lawnmower mishaps (69) and even just falling out of bed (737) than by Islamic jihadist immigrants (two).

A Syrian refugee is not some mysterious, shady, troublemaker we must fight to bar from America or the western world. They are predominantly peaceful heroes, survivors, who need our urgent and undivided support - and if world leaders can't see this, it is arguably not just Douma that is doomed, but the whole of humanity.

Ben Jacobs is a senior journalist with BeIN, ESPN and TalkSport, based in Dubai and reporting from around the Middle East.

Follow him on Twitter: @JacobsBen

![Minnesota Tim Walz is working to court Muslim voters. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2169747529.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=b63Wif2V)