The screams of Ahlam: Harrowing honour killing in Jordan sparks movement for justice

Sarkhaat Al-Nisaa, Arabic for 'the screams of women', is the name of a new campaign which has formed in the wake of the killing.

The group stood outside the Jordanian Parliament on Wednesday to make their demands clear – they want the government to abolish articles in Jordan's Penal Code that allow prison sentences for men who murder their female relatives to be reduced.

The murder of the woman, identified as Ahlam, took place two weeks ago in the Amman district of Safut, but it was only when an audio recording of her screaming and images of her lifeless body in the street went viral on social media that her father was arrested. He has been in custody since 18 July.

Ahlam's neighbours say they heard screams at 9pm on the day of her death and saw her running into the street with her neck bleeding, pleading with people for help because her family wanted to kill her.

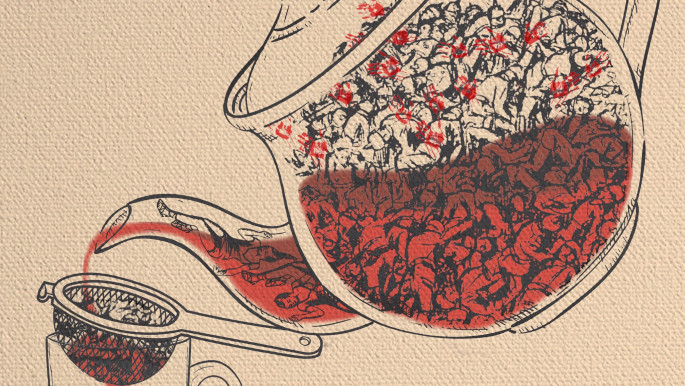

No one intervened as her father came running behind her with a brick and bludgeoned her to death, before sitting down, lighting a cigarette and drinking a cup of tea.

|

The brutal murder of a 30-year-old Jordanian woman has put domestic violence under the spotlight |  |

Paramedics reported that her head was so badly beaten that it had been crushed. Those who knew Ahlam reported that she had asked the country's Department for Family Protection several times for help, convinced her family wanted to kill her.

"The problem with this case is that the victim should have stayed at Amneh House for women whose lives are in danger but she only stayed for a few days…her case was known to have been extreme and that she most probably was going to be killed," journalist Rana Husseini told The New Arab.

|

|

| Read more: 'No honour in murder': Honour killings are a problem and we know it |

The Jordanian journalist started covering the issue of honour killings 27 years ago when it was still a taboo topic, and has written a book on the subject, Murder in the Name of Honour. "They did not keep her for more than two days and in principle, it is hard for a woman to leave [the safe house] on her own," Husseini said.

Ahlam's case is one of the most high-profile murders of women in the region since the death of 21-year-old makeup artist Israa Ghrayeb in the Palestinian city of Bethlehem in August 2019. Many have drawn parallels between the two murders in that again no one intervened at the hospital where Israa was being treated as she screamed while her brothers allegedly beat her to death in her cubicle.

|

A new campaign called Sarkhaat Al-Nisaa, Arabic for 'the screams of women', has formed in the wake of Ahlam's killing |  |

Following Israa's death, thousands of women in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan took to the streets in protest, demanding that their governments change laws that allow a reduction in sentences and calling for tougher penalties.

At the forefront of the Sarkhaat Al-Nisaa movement is Banan Abu Zaineddine, a feminist activist in Amman. "The issue [of honour killings] is present in all of the Arab World, not just Jordan," says Abu Zaineddine.

"I can imagine it happens in most countries, but in other countries they have laws that assist and support women, and the penalties for committing acts of violence against women are clear. We have laws in Jordan that don't help."

|

|

Abu Zaineddine was among those who stood outside Jordan's parliament on Wednesday to call for a number of legislative and administrative changes that would provide greater protection to women and reduce the number of so-called "honour killings."

The most important of these demands are revising the structure of Jordan's Department for Family Protection, and the revision of articles in the penal code that allow reductions in sentences on the basis of the family forgiving the murderer (who is often a member of the same family).

Other requests include calling for amendments to the Domestic Violence Act to ensure effective measures are in place that provide at-risk girls and women with easy access to sustainable protection, and a stronger system of accountability for the Department for Family Protection so what happened to Ahlam never happens again.

Jordan's Penal Code is partly derived from France's Napoleonic Code – the French civil code. Article 340, which allows judges to hand less severe sentences to men who murdered female relatives on the basis of them committing adultery or fornication, was recently repealed in 2018, largely in part to the work of grassroots activists like Abu Zaineddine.

Even though Article 340 has been repealed, a number of other troubling articles remain in place. Article 99 allows a murderer's sentence to be reduced by half the original amount when a member of the victim's family chooses not to pursue legal action or forgives the murderer. The penalty can be further reduced under Article 98 if the defence argues that the crime was perpetuated in "a state of great fury resulting from an unlawful or dangerous act on the part of the victim."

|

If they think that something she has done is bringing shame to their family name, they resort to domestic abuse and killings in the name of honour |  |

An "unlawful or dangerous act" in the eyes of some families in Jordan and Palestine, which share similar penal codes, can be something as simple as a woman setting up a Facebook account, or in Israa Ghrayeb's case, posting a photograph of herself with her fiancé on Instagram.

Article 97, which allows the penalty for a premeditated murder to be reduced if it was committed due to a "fit of fury", also allows convicted murderers to serve as little as twelve months in jail.

Besan Jaber is another Amman-based human rights activist and researcher. She explains how the laws work against victims like Ahlam in Jordan. "The law of sentences and the law of protection against domestic violence in some cases justify these acts or killings as 'an act of anger'. In most cases, the family guardian drops the 'personal right' which leaves it to the 'public right' only. This reduces these sentences."

|

|

| Read more: Trapped with domestic abusers: How Covid-19 lockdowns are endangering vulnerable women across the Middle East |

When it comes to revising and abolishing these articles in the Penal Code, Palestine is ahead of its neighbour. It repealed Article 340 before Jordan did and has already restricted the use of articles previously used to reduce sentences. Jordan may have modern shopping malls, state-of-the-art hospitals and a plethora of tech start-ups, but the country's legal system is decidedly anachronistic.

The Ministry of Social Development records 5,000-6,000 reports of domestic violence each year, with most incidents likely to go unreported. Around 20 women are thought to be killed in so-called "honour killings" each year. So far in 2020, while 11 Jordanians have died as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, nine women have been killed in incidents of domestic violence. But why are attitudes to violence against women so slow to change?

|

There is no intervention from people because unfortunately society considers domestic violence a private matter |  |

Bana Habash, a Palestinian woman who grew up in Jordan, is currently studying International Relations at Florida State University. As well as being a human rights activist, she leads Florida State's Students for Justice in Palestine group, and is currently running workshops for Jordanian activists and feminists to revive women's rights in Jordan.

"The root of the problem in the region is the patriarchy. Societies are filled with misogynists that see women as property, and [believe] that women shouldn't be allowed to live their own lives and make their own decisions…these men see a woman's actions as a reflection of themselves and their 'honour', as if the woman is an extension of them," she told The New Arab.

|

|

"So, when they see a woman's actions as wrong or if they think that something she has done is bringing shame to their family name, they resort to domestic abuse and killings in the name of honour. The actions in question could be simply owning a social media account or getting raped by a man, then having to pay the price for it."

Ayah Al Fawaris, a Jordanian woman who works as an Energy Policy Manager in Leeds, echoes this sentiment, pointing to the role that the media in Jordan plays in the continuation of society's implicit acceptance of violence against women. "The media is one place that is underperforming when it comes to women's rights and honour killings. A well-known TV host was justifying violence just yesterday on TV despite the increasing impact 'a slap' can have on society and how it enables more domestic violence."

For many, one of the harder things to understand is the refusal of people to step in and intervene when they see a woman being harmed by a male family member. "There is no intervention from people because unfortunately society considers domestic violence a private matter," Abu Zaineddine explains.

"Guardianship over a woman is a widely accepted concept in our society so others feel it is not their right to step in. This returns to the concept of the patriarchal society we live in." Jaber agrees. "Neighbours see [it happen] and think 'it is not our place to interfere' which is ridiculous," she told TNA.

Jordan currently has eight women's shelters which are funded by the Government of Norway, the Jordanian Women's Union, UN Women and UNICEF. The first women's safe house funded by the Jordanian government, Amneh House, opened in 2018. These are the first shelters of their kind in the country which provide a comprehensive package of support to women such as psychotherapy, medical treatment, economic assistance, education and professional development.

|

Change is not easy. It needs a huge amount of effort and requires the unity and cooperation of civil society, media outlets and the government |  |

Previously, women who were at risk of being harmed by their families would turn themselves into the police and ask to be incarcerated for their own protection. Women have spent years in prison without charge, terrified that if they leave their families will kill them. While these shelters are a start, oftentimes they are far away and hard to reach, and it is incredibly difficult for women to make it to these shelters without a family member being aware. Hence why Abu Zaineddine and Sarkhaat Al-Nisaa are calling for women's refuges to be more accessible.

The announcement two days ago that Major General Hussein Al Hawatmeh, Jordan's Director of General Security, ordered a restructure of the Department for Family Protection has brought activists like Abu Zaineddine and Jaber in Jordan hope that their demands will be taken seriously this time. Activism in the region has worked before – in 2017 and 2018 pressure from activists resulted in laws that spared punishment for rapists if they married their victims to be abolished in Jordan and Lebanon.

"Change is not easy," says Jaber. "It needs a huge amount of effort and requires the unity and cooperation of civil society, media outlets and the government, and that's what we are hopeful for with the movements that are currently taking place in Jordan, that there will be progress."

Follow her on Twitter: @UNDERYOURABAYA

![President Pezeshkian has denounced Israel's attacks on Lebanon [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2173482924.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=q3evVtko)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News