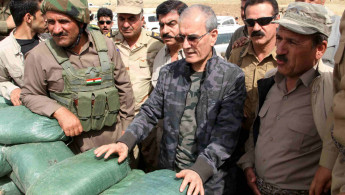

The governor Baghdad wants to remove from office

Karim is disregarding parliament's vote.

Since he became governor through a vote of confidence by Kirkuk's Provincial Council and its people, Baghdad cannot withdraw confidence in him - since they didn't appoint him in the first place.

"I will stay in office," Karim told Reuters. "The referendum will go on as planned… The prime minister does not have the power to ask parliament to remove me."

Iraq's politicians are staunchly opposed to Kurdistan's plan to hold this referendum. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has dismissed it as "unconstitutional [and] illegitimate" - and even once went so far as to glibly declare that he had no plans to send tanks into Iraqi Kurdistan to forcibly prevent the referendum.

Kirkuk remains an area of contention between the Iraqi state and the autonomous Kurdistan Region, both of which claim ownership. While Abadi says the Iraqi Constitution allows him to dismiss any Kurdish independence referendum, he, and the rest of the Iraqi leadership, conveniently ignore Article 140.

This makes it clear that Kirkuk's status should be resolved by a referendum of all its inhabitants, to decide whether they want to become a part of Iraqi Kurdistan or remain part of Iraq. It was supposed to be implemented a decade ago.

Had Baghdad followed the very constitution they are now waving at Erbil, the important issue of Kirkuk's status could have been resolved years ago, and the latest insistence by Karim that Kirkuk participate in the Kurdish independence vote would be much less risky and simple and more clear-cut, straightforward and uncontroversial.

Governor Karim, the man in the middle of this latest dispute, has an interesting back-story. Born in Kirkuk in 1949, he remembers the city of his youth being "an oasis of tea-rooms and movie theatres, where the melting pot of local ethnic groups mixed with ease".

In the 1970s, Karim fought with the Peshmerga against the Baathist regime in Baghdad until its devastating defeat in 1975, when he was in his 20s. He was a physician to the leader of that insurgency, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, the father of the incumbent president of Iraqi Kurdistan, Masoud Barzani.

|

Just weeks before Saddam Hussein gained international infamy by militarily annexing Kuwait, Karim testified in a Senate committee hearing on Iraq's human rights abuses |  |

Karim then lived for three decades in the US where he made his living as a skilled neurosurgeon. During this time he stridently advocated on behalf of the then-largely unknown plight of the Kurds, particularly during the genocidal Anfal campaign which killed 182,000 of them.

He even happened to be in the room following the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981 and told him about the Kurdish struggle.

In an interview with this journalist in February 2016, he recalled how difficult it was back then to draw the attention of the US Congress to the issue, sometimes having to ask his patients who knew someone with contacts to arrange meetings - a striking contrast to the present day, with the Peshmerga and the Kurdish issue having received greater recognition on the international stage in light of their fight against the Islamic State group.

In June 1990, just weeks before Saddam Hussein gained international infamy by militarily annexing Kuwait, Karim testified in a Senate committee hearing on Iraq's human rights abuses. Listing the many crimes of the Iraqi regime, Karim pointed out that 4,000 Kurdish villages were levelled by the Iraqi army, essentially all of the villages in that then agrarian region. When the moderator asked him to clarify that statement, Karim did so, leaving the moderator speechless for a brief moment by the shocking statistic.

Karim did not seek a leadership position in the years immediately following Saddam's overthrow in 2003. Many previously exiled members of the Iraqi opposition had sought to do so, and few received any serious support among Iraqis - since they were perceived as having been installed by US military conquest.

Karim, on the other hand, didn't move back to the region until 2009, and upon building his own base of support was promptly voted into office as governor of Kirkuk in 2011.

|

Kirkuk is an ethnically diverse city: Saddam's Iraq launched a policy of "Arabisation" - the settlement of Arabs from elsewhere in Iraq in the city - in an attempt to shift the city's demographics and undermine Kurdish influence i a bid to exercise complete control over the region's stupendous oil reserves.

The city's infrastructure and economy had been neglected for decades. It was set back even further by horrific terrorist attacks, which took place on a near weekly basis, making Kirkuk almost indistinguishable from the chaos that has so frequently gripped Baghdad, Mosul and other major Iraqi cities since 2003.

Karim brought local economic development by diligently spending an investment budget. An average 4-6 hours electricity per day in Kirkuk was increased to 18 hours. As Iraq analyst Michael Knights observed firsthand when visiting Kirkuk during Karim's third year as governor: "Some of Kirkuk's brand-new thoroughfares and spaghetti junctions recall the early threadbare days of Dubai's rise as a metropolis."

Even Michael Rubin, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a man who has routinely lambasted the Kurdish leadership for years, observed on a visit to Kirkuk in 2013: "Najmaldin is more competent than his predecessors and remains squeaky clean, a rarity in a nation where corruption has since the 1980s been the norm."

There have been criticisms and allegations levelled against Karim, many emanating from within his own party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which, along with Kurdish President Barzani's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), is one of the two most powerful parties in the autonomous region.

Aside from being a member of the PUK, Karim has established a power base of his own as governor of Kirkuk, which has caused some consternation within the party.

In July 2014, he submitted his name to run for the presidency of Iraq without the consent of the PUK political leadership. One PUK official even went so far as to say that his act of unilaterally nominating himself was "an act of turning against the PUK".

Hero Ibrahim Ahmad - the wife of PUK leader Jalal Talabani, who has been incapacitated as a result of a 2012 stroke - also accused Karim last year of colluding with Barzani over the export of oil from Kirkuk. She wrote to Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and asked him to stop sending oil revenues to Erbil, alleging that it was being used in an "unfair and non-transparent way".

On the security front, however, Karim has made impressive progress. Faced with daily, even hourly, threats and lethal attacks on his city when he first became governor, he staunchly declared: "To do this job, you have to stand up to these people and not be afraid."

The governor had a large trench dug around the city. Before that project approximately two to three car bomb attacks rocked the city each week. Today, even after the ascent of IS, they are no longer a frequent occurrence.

While Kirkuk hasn't exactly blossomed, tangible progress was certainly made in Karim's first three years in office - before the rise of IS.

The withdrawal of the Iraqi army from northern Iraq following the fall of Mosul to IS saw the Kurdish Peshmerga forces fill the vacuum and secure Kirkuk.

With the IS war came the influx of 1.6 million internally displaced persons, mostly Sunni Arab Iraqis, into Kurdistan, including a quarter of a million into Kirkuk province, a larger population of Arabs than during Saddam's Arabisation program.

Receiving scant financial assistance from Baghdad to keep the city's employees paid and infrastructure operational, while also relying entirely on the Peshmerga to defend it from deadly IS attacks, Karim commended Kirkuk residents for selflessly sharing "their schools, electricity, medicine, and water with these IDPs".

|

Governor Karim has also been consistent in his advocacy of a special status for Kirkuk, explaining that such a multi-ethnic city cannot be run the same way as homogenous ones |  |

On October 21, 2016, just after the launch of the Mosul operation, IS militants infiltrated Kirkuk city for the first time and attempted to incite an uprising among the large displaced Arab population, not unlike as in happened in Mosul over two years before. The swift response by Kirkuk's security forces, and by locals who took their own guns to fight the militants, quickly foiled the attack.

Karim made a point of acknowledging the contribution these Arab IDPs made to fighting that mortal threat to the city. Two days after the infiltration, some surviving IS members in Kirkuk found shelter with IDPs, probably believing them to be sympathetic with the cause of the caliphate.

Only after feeding these militants dinner and giving them a place to sleep, which they accepted, did the Arab IDPs alert the security forces and have them all arrested.

Governor Karim has also been consistent in his advocacy of a special status for Kirkuk, explaining that such a multi-ethnic city cannot be run the same way as homogenous ones. Even if Kirkuk is peacefully annexed into some future independent Kurdish state, it must retain a certain level of autonomy, with the city's different communities having, in Karim's words, "their own police, control over their own finances and... provisions for the representation and participation of Kurds, Turkmen and Arabs alike for the presidency of Kurdistan, council of ministers, parliament in accordance with their population".

The Iraqi parliament's bid to try and have Karim removed will do little to solve the Kirkuk question.

If they are successful it will, at best, leave the issue unresolved, as their aforementioned neglect of Article 140 has done for a decade. At worst, it would undo the governor's efforts to allow the region to determine its own destiny as well as realise its full potential.

Paul Iddon is a freelance journalist based in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, who writes about Middle East affairs.

Follow him on Twitter: @pauliddon