Times are strange when the sister of a Jordanian taxi driver on death row in Saudi Arabia writes to a former England soccer star asking him to help save her brother's life.

But that is before you consider that Alan Shearer is something of a legend at Newcastle United, a football club which has just been bought by the desert kingdom’s Public Investment Fund. If they cannot pull a few strings back home, then who on earth can?

Shearer, a former player and manager at Newcastle, now a TV pundit, had been very gung-ho about the $US 400m takeover when it was announced, mainly due to his hatred of the outgoing owner, Mike Ashley.

He soon came to his senses about who was taking over the club and penned a thoughtful piece in the sporting bible, The Athletic, about the takeover consortium. The former England captain said he wanted to "listen to the evidence about human rights abuses" in Saudi Arabia and not "brush them under the carpet".

Zeinab Abo al-Kehir took him at his word and told him about her brother, Hussein, who seven years ago was arrested for alleged drug smuggling.

The father-of-eight children had been employed by a Saudi businessman 260 km away in Tabuk where he would work for a month at a time with a week back home in Aqaba.

It is thought that his car was tampered with while parked outside his Jordanian apartment and three bags filled with 290,000 amphetamine pills hidden in the petrol tank.

Zeinab told Shearer what happened after her brother was stopped at a border checkpoint, and his vehicle searched.

"Officers tortured my brother for 12 days until he 'confessed'," she said. "They hung him from the ceiling by his feet, with his head down, and beat him on his face, stomach and hands. We could see the marks this torture left on his body for a year."

Hussein's conviction and sentence of death – based solely on that confession extracted under duress – was seven years ago.

Since then the authorities have made public commitments not only to reduce the use of the death penalty, but also to end it for drugs offences.

In 2018, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) told Time magazine that Saudi Arabia was moving to 'change the death penalty in a few areas to life in prison' where the crime did not involve a situation where 'a person kills a person.'

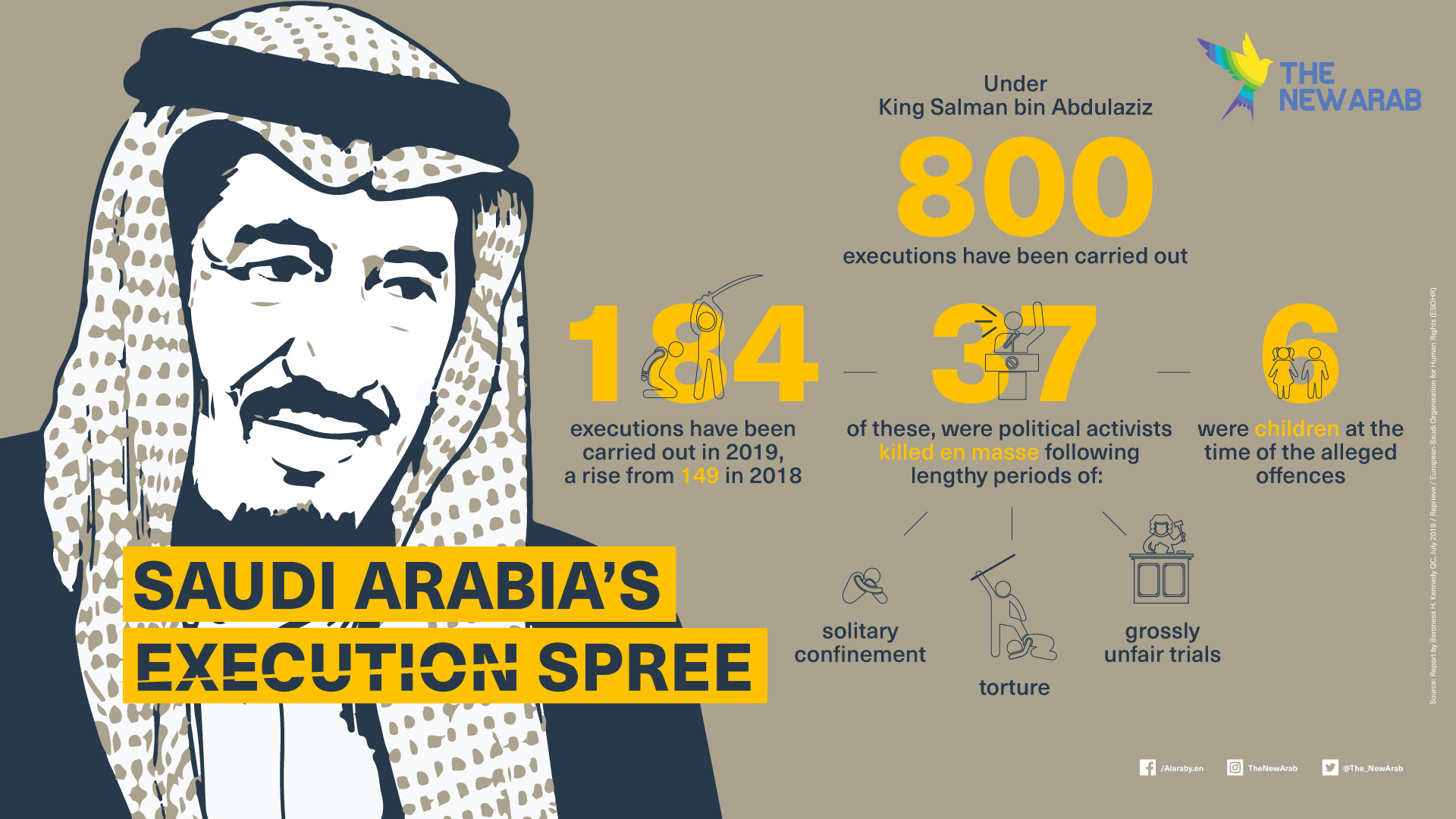

Yet in 2019 Saudi Arabia still executed 185 people, almost half of whom were convicted of drugs offences. Moreover, over 80% of those put to death for drugs offences were foreign nationals; people like Hussein.

The gap between Saudi promises and reality on criminal justice reform is stark. Pledges were made when Riyadh applied to be a member of the UN Human Rights Council and the fact that this bid was rejected in October 2020 might explain the lack of follow-through.

However, Saudi Arabia is still a member of the League of Arab States and bound by Article 6 of the Arab Charter on Human Rights which states that the 'sentence of death shall only be imposed for the most serious of crimes'.

Its execution of a disproportionate number of foreigners is also contrary to the UN Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, which Saudi Arabia joined in 1997, and as such is compelled to "take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists."

Also, by signing up to the Convention Against Torture, Saudi Arabia has pledged to ban torture, investigate allegations of torture and ensure that any statement made under torture – as happened in Hussein's case – is not used in evidence.

Also, by signing up to the Convention Against Torture, Saudi Arabia has pledged to ban torture, investigate allegations of torture and ensure that any statement made under torture – as happened in Hussein's case – is not used in evidence.

So, is there any real change afoot or is it all just a glorified public relations exercise? Was a drop in executions last year due to a change in policy or because the COVID-19 pandemic caused the judicial system to close down and with it a moratorium on all executions during lockdown?

There were 27 executions in 2020, five of which were for drugs offences. This year that rose to at least 60, just one of which was for ‘drugs and political offences’.

While that does illustrate a substantial drop, campaigners are still calling for legislative reform, not just claims by the Saudi Human Rights Commission on Twitter that something has changed. As nothing has officially been announced, family members and campaigners often only what appears in the Saudi media to go on.

Last year, it was suggested that a debate about a policy change on drugs sentencing was underway in the Shura council, the body which advises the royal family.

A leading advocate for reform on the council, Faisal al-Fadhel, a British-educated lawyer, was quoted, saying, "This will improve the kingdom’s reputation and its human rights record, in addition to strengthening communication with other countries of the world and international human rights organisations."

Any change in the law would need to apply to tazir offences for which the penalty is discretionary, but where the death penalty has been widely used, including for drugs offences.

The authorities are fearful of appearing to be going soft on what has become a serious problem. Saudi Arabia is a major narcotics hub, accounting for 30% of the world's amphetamine seizures despite the country accounting for only 1% of the world's population. That is either great policing or the country’s got a major drugs crisis. Yet there is no evidence that the death penalty serves as a deterrent for any offence, particularly drug offences.

James Suzano, a lawyer for the European-Saudi Organisation for Human Rights, said he had been told that a request for a moratorium on the death penalty for drug crime had come from MBS himself, as part of his much-trumpeted reform package. "That it’s before the Shura council is itself noteworthy," he said.

Meanwhile, Hussein is still left languishing in his cell, now 56 and almost blind, suffering excruciating pain in his legs and stomach from the torture he endured. When Zeinab saw a photograph of him behind bars he looked more like her father than her brother, he had aged so much.

Unlike the Saudi prince, who in 2015 was caught trying to smuggle two tonnes of the amphetamine drug, Captagon, on a private jet from Lebanon to Riyadh. The prince - Abdel Mohsen Bin Walid Bin Abdulaziz - was not tortured or sentenced to death. Instead a video of him emerged of him celebrating his birthday in a comfy prison cell with friends and candles. He was later sentenced to just six years in prison.

Clearly, one law for rich Saudi princes, another for poor Jordanian taxi drivers. These are the human rights abuse you say you do not want brushed under the carpet, Mr Shearer.

Anthony Harwood is a former foreign editor of the Daily Mail.

Follow him on Twitter: @anthonyjharwood

Join the conversation @The_NewArab.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.