Last week, after 141 days without food, Hisham Abu Hawash, a Palestinian construction worker from the West Bank, ended his hunger strike in protest of his imprisonment by the Israeli regime. Abu Hawash had been arrested by Israeli forces in October 2020 and was placed under administrative detention, a mechanism commonly used to incarcerate Palestinians for indefinite periods of time without a charge or a trial.

Under administrative detention, there is no time limit on how long a prisoner can remain in custody, and the “evidence” on which the arrest is based is never disclosed. Inherited from the British Mandate in Palestine, the Israeli regime often claims it uses this mechanism in a preventative way, in order to avert “future offences”. Administrative detention orders in Israel last for a maximum of six months, but can be renewed indefinitely.

Human rights organisations and international bodies around the world have decried Israel’s practice of administrative detention as illegal and unjust. UN Special Rapporteur on the Palestinian territories Michael Lynk has called the practice “an anathema in any democratic society that follows the rule of law”.

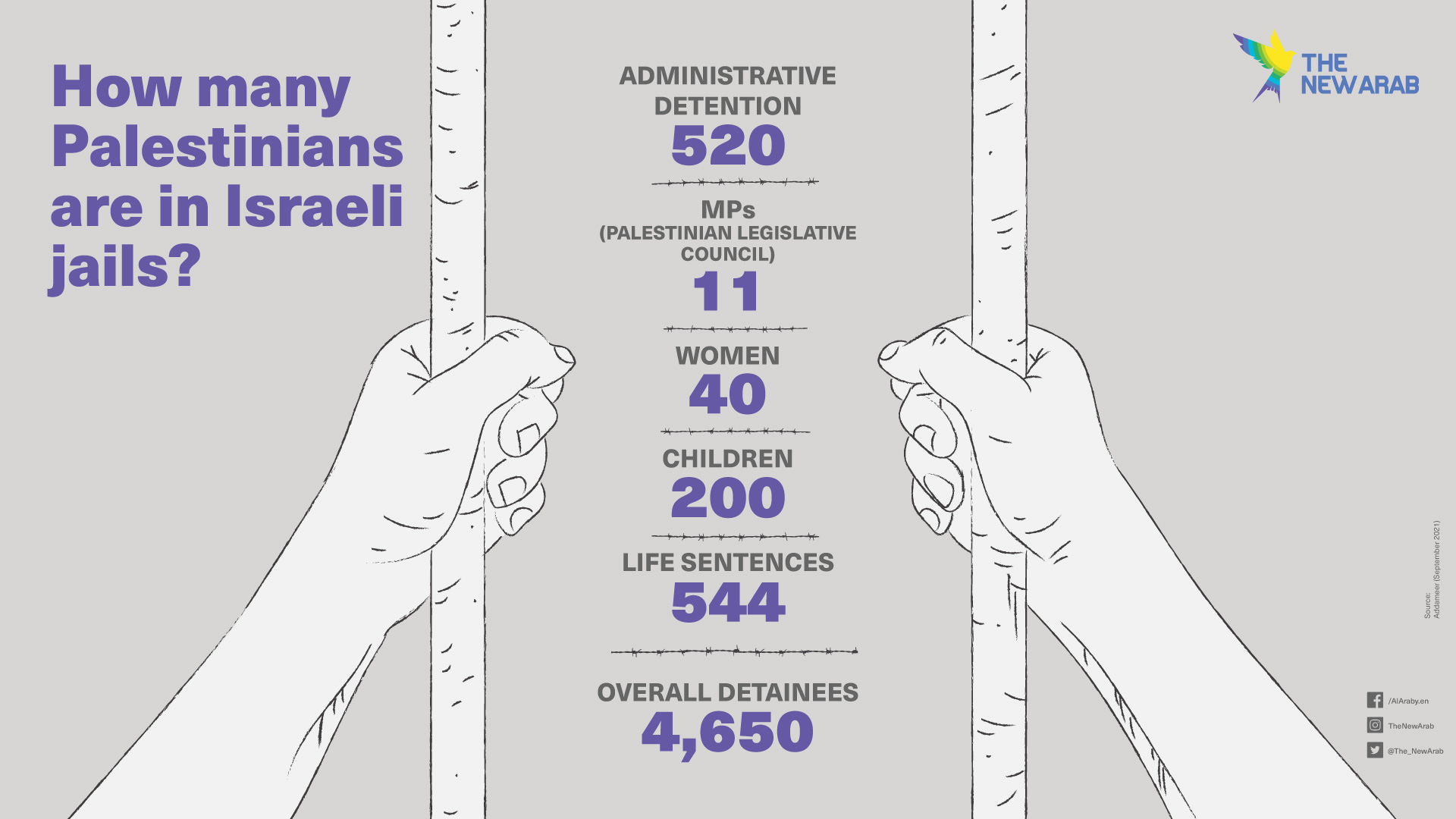

According to the prisoner support NGO Addameer, there are currently 500 Palestinian political prisoners placed under administrative detention in Israeli prisons, many of which have been incarcerated for years.

Yet after nearly five months of hunger strike (and one of the longest strikes in Palestinian history) the Israeli regime was pressured to agree upon a release deal. Abu Hawash’s detention will not be renewed, and he is now due to be released in February.

Palestinians everywhere celebrated this as a small victory in an otherwise ongoing and relentless onslaught of daily incarcerations. Abu Hawash’s resistance and perseverance follows a long history of both collective and individual hunger strikes by Palestinian prisoners.

The longest Palestinian hunger strike took place between August 2012 and April 2013, when Samer Issawi refused food for 266 days before reaching a deal with the Israeli regime. His case drew global attention, and in the face of international pressure and his rapidly deteriorating health, Israel was forced to release him.

|

Hunger strikes have also been used as tools of collective action. In 2017, thousands of Palestinian political prisoners refused food for weeks on end all at the same time demanding basic rights. In some cases, these mass strikes have resulted in deals being reached to improve detention conditions, such as increasing family visitations and better medical services.

Yet often the Israeli regime responds to hunger strikes by punishing the prisoners further- by placing them in isolation, transferring them to different cells and even stopping family visits.

In some circumstances, the Israeli regime has resorted to force feeding hunger striking prisoners- a practice that the United Nations has called tantamount to torture and a violation of international law. In the 1970s and 1980s several Palestinian prisoners died from being force fed by the Israeli authorities, which resulted in a cessation order from the Israeli High Court. However in 2012, the Israeli government reinstated the practice of force feeding Palestinian political prisoners.

Hunger strikes have been used around the world by both activists and political prisoners alike for hundreds of years. In the early 20th century, British and American suffragettes frequently used them as means of protest. Yet they have become more widespread in the last few decades as a means of prison resistance.

In 1981 in Ireland, imprisoned leader of the Irish Revolutionary Army (IRA) Bobby Sands led a collective hunger strike in protest of the removal of the “special status” granted to IRA political prisoners. After 66 days, Sands died, along with nine other strikers.

After Sand’s death, Palestinian political prisoners wrote a letter in solidarity and smuggled it out of the prison. It read, “We salute the heroic struggle of Bobby Sands and his comrades, for they have sacrificed the most valuable possession of any human being. They gave their lives for freedom.”

A few years after the Irish hunger strikers, Black South Africans also embarked on mass hunger strikes in protest of their incarceration by the apartheid regime. Meanwhile, Kurdish political prisoners held by the Turkish state were being inspired by Palestinian and Irish hunger strikers alike.

For political prisoners like those mentioned above, hunger strikes are a means of resistance in a context where they are stripped of all agency and control. Although at first glance hunger strikes may appear antithetical to the struggle for liberation by inflicting damage on oneself, they allow political prisoners to seize back the power of life and death from the incarceration regime.

As Palestinian scholar Dr. Malaka Shwaikh writes, “The prisoners’ power is embodied in their choice of action, and their ability to start and end it whenever they want. Through their strikes, the prisoners claim the ownership of their own bodies and even lives.”

Indeed Hisham Abu Hawash, and thousands before him, have embarked on this practice as one of the only tools at their disposal to reclaim power and resist the Israeli regime. And until Israel’s brutal incarceration regime ends, no doubt many others will follow in his footsteps.

Yara Hawari is the Palestine Policy Fellow of Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network.

Follow her on Twitter: @yarahawari