Will we finally accept that 'precision airstrikes' don't exist?

“Strive.” “Lawfulness.” “An honest mistake.” “Unintended consequences.” “Access to classified intelligence.”

These are words that come up repeatedly in US justifications of “regrettable” civilian casualties caused by US or US supported military operations. The US military responded similarly to this week’s bombshell investigative reporting by Azmat Khan in the New York Times revealing that Pentagon documents regarding alleged civilian harm in 1,311 airstrikes in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan — the “Civilian Casualty Files” or CCF — highlight “a system of impunity” rather than a system of accountability in the US post-9/11 wars.

Just as the Air Force Inspector General found in an investigation into the now infamous August 29 drone strike of Zemari Ahmadi and his family in Kabul, Afghanistan, the Pentagon didn’t find any “wrongdoing” in the CCF. It instead focused on ways to “improve process” in order to avoid such situations in the future.

The military’s hindsight reveals flaws but nothing nefarious; there was no wrongdoing in these strikes because it was not the drone operator’s, or the military’s intent to kill civilians or misidentify them, rather it was a miscalculation of the estimated costs to civilians.

"Debating the legality of individual strikes or admitting the need to improve the strike process misses the forest for the trees: this investigation shows, once again, the very idea of a precise air warfare is flawed"

Debating the legality of individual strikes or admitting the need to improve the strike process misses the forest for the trees: this investigation shows, once again, the very idea of a precise air warfare is flawed and attempts to make it more humane only reinforce the entrenchment of the status quo.

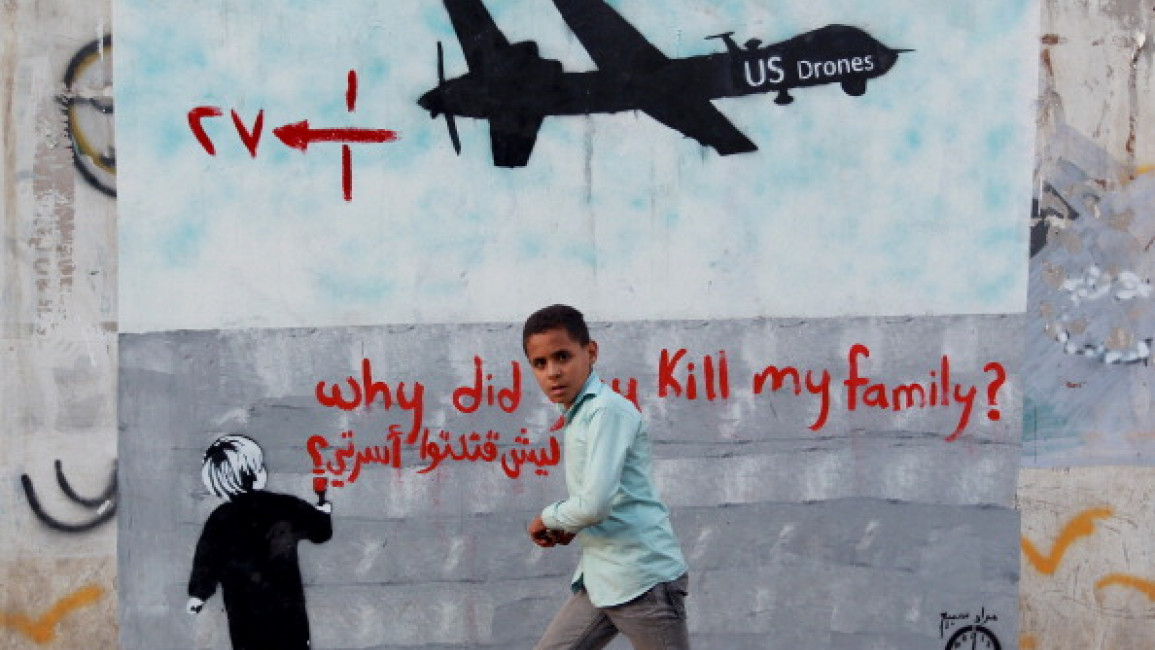

The US military’s intent behind these strikes does not matter to the hundreds, possibly thousands of unacknowledged civilian victims of US “precision” airwars over the last two decades. It does not matter to survivors of drone strikes that killing a handful was worth killing hundreds.

The egregious human costs of the US drone and air strike campaigns are a failure, but also a symptom of larger strategic dissonance in US counterterrorism doctrine. The Times report shows, time and again, that the intelligence prompting target tracking and, in part, strike authorisation, is flawed.

The misidentification of the target, often due to confirmation bias, and the presumption of guilt, keep the institutional incentives behind continued airstrikes. Moreover, the myth of surgical strikes doesn’t hold up when thousand pound payloads are dropped in urban or residential areas, no matter how precise the weaponry.

The military’s own confidential assessments of over 1,300 reports of civilian casualties since 2014, obtained by The New York Times, lay bare how the air war has been marked by rushed and faulty targeting, despite promises of precision and transparency. https://t.co/6VCYUtSZXf pic.twitter.com/QKdqbK38Ah

— The New York Times (@nytimes) December 18, 2021

Meanwhile, the underlying factors driving support of armed nonstate groups — government corruption and/or non-presence, lack of economic opportunity, insecurity and state violence — remain unaddressed. Civilian-harming US drone strikes (often in alliance with the local ruling authority) then provide fresh fodder to inflame these grievances for mobilisation.

Never mind the fact that the very threats these strikes are supposed to address were very much born from previous US military misadventures in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. Instead, we continue to implement policies that terrorise children in response to our own perceptions of insecurity.

For all its boasts of reviewing “lessons learned,” the decision to keep the systematic harm to civilians produced by US drone wars hidden from public view sure seems like evidence of an attempt to paper over those lessons, and the larger ineffectiveness of the endless war enterprise they expose.

As the United States expanded its endless post-9/11 ground wars into drone wars across the Levant, Central Asia, and Africa, the question of whether and under what auspices these wars were happening became less and less transparent. Revealing the true costs of remote warfare presents an inconvenient truth for the US military as the Biden administration seeks to pivot to a new era of counterterrorism and great power competition.

According to administration officials, this approach will be guided by investing in the capacity of partners to fight these wars for us, combined with “over-the-horizon” operations, cybersecurity, and law enforcement efforts. That’s less a pivot to the future than a re-emphasis of certain tools already in the toolkit, belying a fundamental misunderstanding of the challenge at hand.

It isn’t a critical evaluation of the last 20 years, or the very strategy that has guided the expansion of these wars. And it doesn’t address the flaws identified in the CCF or the broader post-9/11 wars following multiple nation-building failures.

The “Civilian Casualties Files,” just like the “Afghanistan Papers” before it, are yet more evidence that the US government — at the very least the US military — knew the costs and failures of these wars, decided the collateral damage was acceptable, and continued on with bombing as usual.

Will these files help create momentum for accountability? If it’s left up to the military and the president, the apparent answer is a resounding “no.” The question remains, what will Congress’s response be, and if any change will finally come.

Kate Kizer is the Policy Director at Win Without War. She has nearly a decade of experience working on human rights, democratization, and U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East.

Follow her on Twitter: @KateKizer

This article originally appeared on Responsible Statecraft.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed here are the author's own, and do not necessarily reflect those of her employer, or of The New Arab and its editorial board or staff.