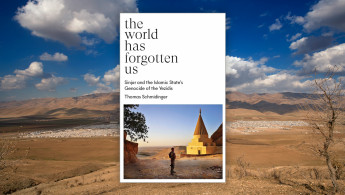

The World Has Forgotten Us: Sinjar and the Islamic State’s Genocide of the Yazidis

The Yazidis, an ethnoreligious group of around half a million people mainly living in Iraq, were catapulted into the global news cycle in August 2014.

During that month, the so-called Islamic State (IS) made rapid advancements in Iraq's northwestern Sinjar region.

The area, which is the homeland of the Yazidi people, saw how more than 3,000 adherents to this ancient faith were killed while 6,000 were captured.

The Yazidis had a long history before the tragic summer of 2014. In its current form, Yazidism dates back to the twelfth century, although it is certainly older. And, despite the most brutal form of intolerance displayed by the IS and the death and displacement brought by it, the Yazidis also have a future.

"Schimidinger’s book has a strong virtue. The sympathy for the plight experienced by the Yazidi people does not come at the expense of leaving aside some of the most controversial aspects of Yazidism"

In his latest book, The World Has Forgotten Us: Sinjar and the Islamic State’s Genocide of the Yazidis, University of Vienna Political Scientist and Anthropologist Thomas Schmidinger presents two key realities.

On the one hand, the efforts by IS to destroy the Yazidis are by no means an isolated event but represent the culmination of centuries of discrimination.

On the other hand, the Yazidis are much more than a long-prosecuted people. Rather, they are a group with distinct cultural and religious practices that have traditionally been poorly understood. One of the most commonly held myths is that the Yazidis are worshipers of the devil.

Such a trope has played a central role in the vilification of Yazidism over the centuries, most recently in the dehumanization that led to the massacres of Yazidis at the hands of IS members.

The World Has Forgotten Us is structured into two parts. The first one is an essay that covers the Yazidis’ history up to the present day. Although it is logical that the focus of the historical account is on the last century, the reader would probably have liked to learn more about the Yazidis’ ancient history, to which Schmidinger dedicates a few pages.

The second part of the book is a collection of interviews with prominent Yazidis conducted by the author over the years. The volume also features photographs taken by the Austrian academician during his research on the ground.

One of the constants in the history of the Yazidis is state attempts to rein in their autonomous organisation.

During the nineteenth century, different Ottoman generals were tasked with imposing taxation in Sinjar. In 1915, the ancestral lands of the Yazidis would become a refuge for thousands of Armenian Christians fleeing Ottoman prosecution.

With the creation of an independent state in Iraq and its strengthening in the following decades, the Yazidis were subjected to a new level of state interference. For the Yazidis living in the Sinjar mountains, “the period of Ba’thist rule over Iraq represented a massive caesura in their traditional lifestyle.” (p. 46)

Under Saddam Hussein, indigenous Yazidis were deported from their villages and re-settled in collective towns. The situation after the downfall of the Iraqi dictator was not necessarily better.

With the change of regime, some Muslim Arabs resettled by Saddam to Sinjar started to gravitate towards the jihadist underground. They “regarded the occupation of the country by the United States and the presence of Kurdish militias as humiliating.” (p. 53) In August 2007, two truck bombings masterminded by al-Qaeda left more than 500 Yazidis dead.

"Thomas Schmidinger presents an account of the Yazidis living in northern Iraq that eschews simplistic narratives presenting the Yazidis as nothing more than the victims of genocide"

The 2007 terrorist attacks were the prelude to the 2014 Yazidi Genocide, recognised as such by the UN and the European Union and numerous national parliaments.

The ultimate responsibility for the atrocious acts perpetrated on the Yazidis undoubtedly lies in the hands of IS members.

This notwithstanding, many Yazidis believe that the peshmerga, the military forces of the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, could have bought time for more Yazidi civilians to escape to the Sinjar mountains and Syria if they had put up a fight against IS in August 2014 instead of withdrawing.

In an interview with the author, Haydar Shesho, the commander of the HPÊ Yazidi militia, expressed his conviction that “the KDP [the largest party in Iraqi Kurdistan] were quite content to leave Sinjar and that there was an agreement with IS allowing it to take over.” (p. 178)

In weighing in the different strands of evidence, Schmidinger notes that the secret agreements concluded during those convulsed days were very opaque.

Still, there is no denying that the peshmerga of the KDP retreated without a fight in August 2014, and “hesitated for a long time to advance in the direction of the mountain regions,” (p. 91) where the Yazidis were deeply in need.

The Yazidis that suffered the worst fate were the ones living in the southern areas of Yazidi settlement in Iraq, further away from the Sinjar Mountains and northern Syria.

That was the case of Kocho, one of the collective towns created under Saddam. In that town, 600 men and boys were slaughtered by IS. Women survived, only to be enslaved and subjected to sexual violence.

Nadia Murad, the Yazidi human rights defender who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018, is originally from Kocho.

"The World Has Forgotten Us: Sinjar and the Islamic State’s Genocide of the Yazidis is thorough in its approach but accessible in its style. It represents a key work in the path of making Yazidism in Iraq better understood"

Schimidinger’s book has a strong virtue. The sympathy for the plight experienced by the Yazidi people does not come at the expense of leaving aside some of the most controversial aspects of Yazidism.

Traditionally, Yazidis have shunned and even killed women from their group who engaged in sexual intercourse with non-Yazidis, regardless of whether the relationship was consensual or not.

Consequently, women would even face punishment for being abused. After the return of many Yazidi women subjected to sexual violence by IS, the Yazidi spiritual leader Baba Sheikh worked against these practices and introduced a baptism ritual that welcomed these women back into the community.

|

What happens, however, when women voluntarily want to establish a relationship with a non-Yazidi, something that is happening more often in recent times due to the large number of Yazidis living abroad after the genocide?

Akhin Intiqam, commander of the female YJŞ Yazidi militia, explains to Schmidinger that the group she leads tries to convince women not to marry Muslims.

Questioned by the Austrian researcher on whether this may contradict the emancipatory spirit of her political movement, she replies that this is not the case because “they don’t kill these girls but only give them advice and try to convince them by arguments.” (p. 227)

Thomas Schmidinger presents an account of the Yazidis living in northern Iraq that eschews simplistic narratives presenting the Yazidis as nothing more than the victims of genocide.

At the same time, it is obvious that the Yazidis need help both from within Iraq and internationally to return to their ancestral lands with safety guarantees, especially considering that former IS members continue to live in northern Iraq.

The World Has Forgotten Us: Sinjar and the Islamic State’s Genocide of the Yazidis is thorough in its approach but accessible in its style. It represents a key work in making Yazidism in Iraq better understood.

Marc Martorell Junyent is a graduate in International Relations, currently finishing a MA in Comparative and Middle East Politics and Society at the University of Tübingen (Germany). He has been published in the London School of Economics Middle East Blog, Middle East Monitor, Inside Arabia, Responsible Statecraft and Global Policy.

Follow him on Twitter: @MarcMartorell3

![Yazidi children hold photos of family members killed by ISIS as members of the Yazidi ethnic community from Iraq who escaped death and persecution at the hands of ISIS [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-05/GettyImages-1159793589.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=BuMhUIjb)