Praying to the West: Uncovering Muslims' deep roots in the Americas

In 2017, a mass shooting at a Quebec City mosque left six worshippers dead, five others seriously wounded, and an entire community of Muslims traumatised.

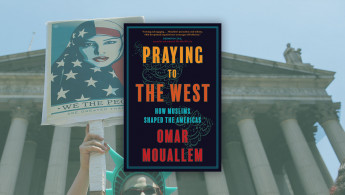

For Omar Mouallem, an Arab-Canadian writer who grew up in a Muslim family, the shooting brought home the reality of anti-Muslim hate in North America. But it also sent Mouallem on a journey of self-reflection, international travel and historical exploration that he captures in his new book, Praying to the West: How Muslims Shaped the Americas.

"You can actually capture quite a bit of the 1500-year history of Islam, I think, by looking at one city in the Americas and examining its different denominations, Sufi inflections and mosques. I don’t think you can do that in Beirut or Cairo, and certainly not Mecca"

Part travelogue, part memoir, this cultural history of Islam in the Western Hemisphere follows Mouallem’s travels to dozens of mosques, discovering Muslim communities worshipping from the Arctic Circle to the edge of the Amazon. Through meeting indigenous Mayan Muslims in southern Mexico and congregants at a 170-year-old mosque in Trinidad, Praying to the West traces the pasts, present, and futures of diverse Muslim communities throughout the Americas.

Mouallem aims to “normalise” Islam, in all its heterogeneity, as part of the broader American religious landscape. But in excavating these forgotten histories of Islam's influence and glimpsing the expansiveness of the ummah, he also comes to better understand his own fraught relationship with Islam.

|

What do we gain when we put these diverse Muslim communities in conversation with one other?

"One of the most unique things about greater American Islam, and maybe its defining feature, is just how diverse it is. Here in Calgary, there are probably 30 mosques and probably 12 different branches with decently sized communities. That's just one typical Western city. You don't necessarily find that kind of denominational diversity in African, Middle Eastern, South Asian cities where there is a large Muslim population.

And you certainly don't find that kind of ethnic diversity — Muslima are the most ethnically diverse religious group in the US, and you probably extrapolate that to the rest of North America. When you put these groups in conversation, you see how even Muslims who subscribe to the same branch developed in culturally different ways.

You can actually capture quite a bit of the 1500-year history of Islam, I think, by looking at one city in the Americas and examining its different denominations, Sufi inflections and mosques. I don’t think you can do that in Beirut or Cairo, and certainly not Mecca. It's maybe a provocative thing to say. But I think if you were to do a deep dive into all the mosques of a city like Houston versus a city like Mecca, you'll walk away with a much better understanding of Islam."

How did this book project evolve as you worked on it?

"As a travel writer, a travelogue seemed the logical way to unearth the continental history. When I went up to the Midnight Sun Mosque in Canada's Northwest Territories, that's when it all clicked together that the framework would be profiles of mosques.

From every mosque, you could move in concentric circles to the congregants, the leadership, their conflicts and issues, the broader region, the city, the province, the country, the homeland if they're immigrants. Then you come back to the mosque. It's a kind of time portal.

"What surprised me is it started to feel that, whether or not we hold firm to the exact same beliefs, we have a lot in common — going to mosques, spending Eid with a community, relating to people. We have a shared experience."

The book wasn't supposed to be so personal. Once it came time to get into the story, I just found myself inserting my inner thoughts, and then my memories, and that turned into baring my soul. But it felt like it felt more ethical that way, to be very transparent about where I'm coming from, where I've been — spiritually, or lack thereof — and where I can feel myself going."

How did working on this project reshape your personal faith and identity?

"What surprised me is it started to feel that, whether or not we hold firm to the exact same beliefs, we have a lot in common — going to mosques, spending Eid with a community, relating to people. We have a shared experience. Over the past few years I’d been experiencing more racism, and I realized that whether or not I call myself Muslim, people assume I am. And there are certain values, traditions and rituals that I still cherish.

So I started to wonder if there was a place for someone like me. That became a challenge, a test — if there is, where would I find it and what would it look like? I felt like reclaiming my Muslim identity on my own terms and in claiming a spot in it felt like a just to do.

|

|

Everywhere I went, I met Muslim people who were called illegitimate — people who were very observant, very pious, extremely faithful, sometimes dogmatic. And there was always someone else who was telling them, “You're not a real Muslim.” Something that challenged me was meeting people from the Moorish Science Temple and recognising some judgment within myself, where I was questioning whether they are legitimate Muslims. And then I was like, “Well, why not?”

Going to their conferences, I saw efforts to wrestle with the original text and syncretise it with more orthodox Muslim traditions. They have a lot in common with other Muslim communities because of their beliefs. They see themselves as Muslims. So why aren’t they a part of the ummah?"

As you examine early Arab settlement in the North American prairies, you write about your immigrant community’s complicity in Indigenous genocide. Amid a national conversation about residential schools, how are Arab and Muslim immigrants engaging with this topic?

"These communities are starting to acknowledge and respond in a productive way. A friend told me about how the Imam’s Friday sermon at her mosque was about the history of residential schools and encouraging both compassion and action for equity among Muslims.

It is still difficult for a predominantly immigrant community to understand. In my immigrant community, there is a bootstrap mentality and a gruff pride in it. My uncles, my father, take pride in being self-made men. There's truth in that, but there was also a pretty established community supporting them. It’s difficult for them to understand how deep-rooted and lasting the trauma of residential schools is, because many, like my mum, come from war-torn places. That makes it easier to overlook just how awful and real the genocide was in Canada.

A lot of Arabs, when they think of settlers, they think of settlers in Israel. To put that label on themselves is a hard pill to swallow. But it has to be acknowledged."

Aysha Khan is a journalist covering American Muslim communities.

Follow her on Twitter: @ayshabkhan