Why did an Egyptian film showing poverty cause a stir in a country where poverty exists?

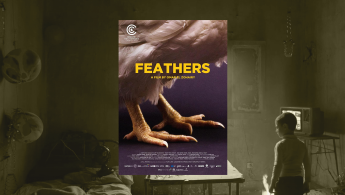

Seems like the Egyptian film, Reesh, definitely ruffled some feathers after it was premiered at the fifth edition of the El Gouna Film Festival on the Red Sea coast this month.

The award-winning film, which translates to Feathers, stirred up a heated debate in the country for portraying an impoverished local family, despite this being a stark reality for many. Pro-regime media outlets and social media users denounced the film crew for presenting the 'ugly' part of Egypt, while a number of Egyptian celebrities angrily walked out of the film's premiere.

So what caused such a negative response?

Taking on the theme of a dark comedy to tackle the issue of poverty in Egypt, Reesh revolves around an impoverished house in a seemingly disadvantaged village or squatter settlement. It follows the story of a woman whose husband is transformed into a chicken after a magic trick goes wrong, leaving the wife to undergo a personal ordeal to support her children in the absence of the family’s patriarchal figure.

For the celebrities who withdrew from the premiere, Reesh did not depict the 'new Egypt' that the current regime of President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi had been creating.

"Pro-regime media outlets and social media users denounced the film crew for presenting the 'ugly' part of Egypt, while a number of Egyptian celebrities angrily walked out of the film's premiere"

“I got out of the [hall] because what the film depicts is improper. It portrays a family living in agony… I felt suffocated. Even the slums that used to exist [in Egypt]… are no longer there. I like our homeland to look [decent],” celebrated actor Sherif Mounir told talk show host Amr Adeeb on the El-Hekaya TV show broadcast on MBC Misr.

But film producer, Mohamed Hefzy, begs to differ.

“The film is merely a human-interest [story]. Had it caused any insult to Egypt, I wouldn’t have produced it. The [fact that] it won a Cannes award made us all proud as Egyptians,” movie Hefzy told local privately-owned Al-Shorouk newspaper.

“There are aesthetic [aspects] in the film… that have nothing to do with politics, but, [rather] with humanity,” Hefzy added.

Directed by Omar El-Zohairy, Reesh is the first-ever Egyptian movie to win the Grand Prix and the FIPRESCI Award of the 2021 Cannes Film Festival's Critics' Week earlier in July this year. Most recently, Feathers won the Best Film under the Roberto Rossellini Awards during the annual Pingyao International Film Festival in China, along with a $20,000 prize.

Surprisingly, the Egyptian Minister of Culture, Enas Abdel-Dayem, had honoured the film crew in July after their triumph in Cannes, describing their win as “a historic achievement,” which may now put her in a critical position following the recent debate.

"In a country where almost one-third of the population lives below the poverty line, and whose president recurrently refers to his people as being 'very poor' it should not come as a surprise that a work of art is portraying this very poverty"

A few hours after the festival incident, social media platforms turned into a war zone, with those supporting the film crew members and their right to artistic creativity while others suggested that the film underestimated the government's efforts at combating squatter settlements and providing a better life for the poor.

However, in a country where almost one-third of the population lives below the poverty line, and whose president recurrently refers to his people as being “very poor” it should not come as a surprise that a work of art is portraying this very poverty.

|

| Translation: What [the withdrawing actors] don’t know is that 40% of Egyptians live a life like the one depicted in Reesh |

|

| Translation: This is my response to the traitors after they had posted old pictures of squatter settlements that have nothing to do with today’s Egypt |

In a move that violates artistic freedom, notorious lawyer Samir Sabry filed two complaints, one before the prosecutor general and another before the state security prosecutor against the film crew.

Sabry accused the director, scriptwriter and producer of “insulting the Egyptian state by deliberately depicting an unrealistic, offensive image of the life of Egyptians and the Egyptian society.” He called for the case to be referred to an urgent trial before a criminal court. The status of his complaint has not been determined yet by the prosecutors.

“The debate was on squatter settlements and poverty. Sisi has been addressing the problem for some time now. They just want to say it is over and there is no need to show it,” prominent political sociologist Dr Said Sadek told The New Arab.

“Interestingly, the movie had been approved by the Egyptian censorship authority; but it now gets banged for political reasons. The critics aim at showing their loyalty to the regime,” he argued.

However, several artists and public figures were quick to voice their support for the film crew and freedom of speech and creativity.

"The debate was on squatter settlements and poverty. Sisi has been addressing the problem for some time now. They just want to say it is over and there is no need to show it"

Prominent director Kamla Abou Zekry wrote on her official Facebook page: “For those who bid on their patriotism, [stop using] Egypt’s ‘reputation’ [as a justification] …a provocative word that underestimates Egypt. Shame on you…enough with the hypocrisy…and making yourselves the guardians of Egypt.”

Award-winning journalist, former CNN correspondent, and ex-deputy head of Nile TV International, Shahira Amin agrees with Abou Zekry.

“Defaming Egypt’s reputation starts with narrow-mindedness and the terrorisation of creators and [treating them like] traitors… not with a work that highlights the already existing poverty, even sometimes, uglier than what is shown in the movie,” she wrote on her Facebook page.

In fact, Egyptian cinema has never been free of controversy. In 1991, late award-winning, international director Youssef Chahine directed a docudrama in which he appeared himself, entitled Le Caire. The film depicted poverty, slums, over-crowdedness, and several other unpleasant aspects of the Egyptian capital Cairo, and like Reesh, received a lot of backlash despite it merely revealing reality. Several other films produced throughout the past few decades depicting social realism have raised controversy in Egypt as well.

However, following this recent debate in the country, the commercial fate of Reesh and whether it will be screened in Egyptian cinemas in December as earlier scheduled remains unknown.

Thaer Mansour is a journalist based in Cairo, reporting for The New Arab on politics, culture and social affairs from the Egyptian capital.