A World Cup for all: How Qatar's relaxed entry rules made it one of the most inclusive tournaments in history

Now that World Cup fever is slowly fading and 2023 has begun, what do we have to look forward to in our lives…

At the 2026 World Cup, the tournament will expand from 32 to 48 teams for the first time in its history. Asia will see its confirmed participation slots rise from 4 to 8, with Africa’s rising from 5 to 9, giving hope to millions of football fans around the globe whose nations have never qualified within their lifetimes.

For Iraqi fans, whose national team currently sits at 68th worldwide, and 7th in Asia on FIFA’s rankings, it would be poetic to qualify for the 2026 edition held in the US, Canada and Mexico, knowing their last appearance was in Mexico in 1986.

The top 8 spot looks achievable, and should they do it, the nation will ascend into euphoria. Long into the night the celebrations, fireworks and gunshots will ring out in celebration of the Lions of Mesopotamia; but as the dust settles the next morning, the elation will fade.

"It’s ironic... the process of travelling through the Jordanian airport was a much easier experience than any Israeli checkpoint"

Iraqi football fans will come to the realisation that the majority of them will not be able to see their country compete on the global stage, in person. These supporters know that draconian border force laws will render their dreams invalid, with their passports being ranked 2nd weakest on Earth in terms of visa-free movement. This is a struggle that will not be faced by Iraqis alone. Many fans from the continents of Asia and Africa will suffer, and it’s at this moment that we will reminisce on how open the 2022 World Cup in Qatar was.

It’s all in the name. It was actually a cup for the world. Pundits, players and fans alike from all over have commended Qatar for its handling of the tournament, allowing in visitors who would otherwise struggle to be able to witness most of the previous editions. This article will delve into the accessibility of the tournament, which, according to a BBC poll, was the best World Cup of the century.

Qatar Tourism recently released a statistic showing that over 600,000 international fans visited the country in November 2022, and the results were fascinating.

|

Which other tournament could you see such a diverse range of fans, when these tournaments have previously been dominated by support from Western Europeans and South Americans? We saw a plethora of cultures and native dresses. It was a moment for international cultivation and education, with almost every team having a special version of a thobe (traditional Middle Eastern and North African men’s dress) with their nation's flag upon it.

|

Throughout the duration of the tournament, Qatar’s visa system was innovated through its implementation of the Hayya card, a fan ID that grants supporters access to the country.

From the knockout stages onwards, even ticketless fans were able to apply for a Hayya card too, giving even more freedom to those who wanted to experience the event. The Hayya card offered fans a free sim card, free travel, access to fan experiences, and a number of other complimentary benefits.

How did Qatar achieve such an open-door policy? It offers visa-free entry to over 95 countries, including Pakistan, Lebanon and Iran, which are respectively the 4th, 15th and 17th worst passports on earth.

The weakest passport from all qualifying countries to the 2022 WC was Iran, and it is they who will also be feeling apprehensive about entry to the 2026 WC. If they do qualify, will their fans, and even their players feature too?

It was reported in July 2022 that Iran’s national archery team were denied visas to the US, ruining their chances of competing in the World Games; 2026’s other host, Canada, cancelled a friendly game with the Iranian national football team that was set to be hosted in Vancouver, just a month earlier.

Muslims worldwide will acutely remember that in early 2017, the then-President of the United States Donald Trump enforced a set of orders labelled as the “Muslim travel ban” by critics. Instantly, citizens from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen were banned from entering the USA for 90 days.

The United 2026 bid was unveiled on 10 April 2017. What kind of message is being displayed when this coalition of countries is actively pitching their willingness to host the world’s largest sports tournament during a time in which seven nations, whose accumulative populations are over 200 million people, are banned from entering the US?

|

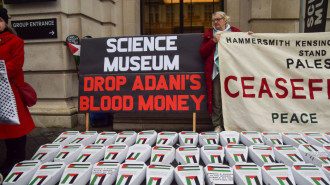

Another group of fans who don’t have much hope of attending the 2026 WC are the Palestinians. The “Palestinian Territories” passport is ranked 7th weakest on earth, allowing visa-free access to only 38 countries worldwide. What about the many Palestinians who don’t even hold passports?

I spoke to Adnan Barq, a filmmaker from Al Quds (Jerusalem), about his World Cup experiences. He attended with friends and delved into some of the difficulties that Palestinians face while travelling.

“I’m from Jerusalem, but I have an Israeli ID. I have Jordanian travel documents, but I’m stateless and have no registered nationality, so it was really confusing to identify ourselves on the application forms,” he recalls. “After a few attempts, all of my friend’s visas were accepted and mine was still pending. I thought I wouldn’t receive it in time.”

His friends flew ahead of him in the hope they could find a solution, and upon landing at the airport they went directly to the Hayya helpdesk, where one of the workers was able to sort out the issue within 30 minutes.

With that, Adnan was off to Qatar. “It’s ironic,” he comments, “the process of travelling through the Jordanian airport was a much easier experience than any Israeli checkpoint,” albeit his first time ever travelling via a plane.

The other option for travel was via the Israeli Ben Gurion airport, using their Israeli IDs, and it would have technically been quicker. However, Adnan and his friends wanted to end any possibility of being humiliated by Israeli airport officials, who have been known to harass and degrade any Palestinians who pass through. He was wary that they would feel the bitterness of Israelis who were upset at how their journalists were being ignored in Qatar.

“We just wanted to be treated like human beings, and in the end, we made the right decision,” he says proudly.

The experience was mind-blowing for him, with the level of Palestinian solidarity on show being something that he’d never expected. “Zionists always tell us that we’ve been left alone; that the Arabs hate us, and that the Palestinian cause is boring,” he expresses “but this was a beautiful experience that threw it all right back in their faces.”

He has since returned home and has said that he’s still processing all of the imagery and the atmosphere that he witnessed and that he was in awe the majority of the time.

As he donned a large Palestinian flag in public for the first time in his life, he reminisced about the support and kindness he received from everyone he came across, feeling privileged to hear the unregulated voices of all citizens who were in support of Palestine.

“You know during Ramadan when you’re fasting for the entire day and you’re so hungry, and the Adhan (call to prayer) is heard, and then we eat everything that we can eat, and then we die,” and it’s this relatable anecdote that perfectly sums up exactly how overwhelmed he was.

Another attendee from Palestine was Momen Faiz Quraiqea, a photojournalist, and filmmaker originally from Gaza. Momen was only 21 years old when an injury from an Israeli airstrike resulted in him needing to have both of his legs amputated, leaving him in a wheelchair for life.

With photography being his passion from the tender age of 16, he and his camera has become inseparable. After surgery, his wife encouraged him and supported him in returning to his dream. Despite his injuries, he has become one of the most established photographers in Gaza, whose work has been recognised internationally, so much so that the Qatari Foreign Ministry personally invited him to come and document the World Cup.

“Covering the World Cup and even attending the World Cup is something that is not easy to coordinate or even reach, especially from Gaza, but I found things to be easier when I actually arrived in Qatar,” he stated.

When asking him about his experiences as a wheelchair user at the World Cup, he responded “From the very first moment of our arrival at the airport, I was able to move without an escort because everything felt inclusive. All of the public facilities, streets, cars, the metro and stadiums had ease of access. I was very happy with this experience. I wish that the Qatar version of the World Cup will be able to be circulated worldwide.”

In the broader sense of the word, when talking about accessibility, it’s clear to see that Qatar did more than open doors to nations; it opened doors to those who needed special assistance, as well as also opening doors to parents.

Doctor Mohammed Shaath, from Manchester, travels to Doha every year to visit his family who lives there. After arriving mid-tournament, the fantastic reviews gave him the confidence to take his seven-year-old son, Nabeel, to watch the Morocco-Croatia semi-final.

“The atmosphere was buzzing… Nabeel was so into it, and now he wants to play for the Moroccan team, so much so that he asked me if he has to learn the national anthem,” all the more hilarious as Nabeel is of Palestinian heritage.

"I’ve always wanted to attend such tournaments, but male-dominated environments tend to make me feel uncomfortable. The Qatar World Cup was a family-friendly tournament"

As a father, Mohammed is against taking his children to a football game in the UK. “I feel unsafe at matches sometimes, never mind having my son with me,” he tells me. “I probably won’t take him to a match in England until he’s a lot older… If we were to go now then I wouldn’t be able to let go of his hand, but in Qatar, I was so reassured that he could roam free,” albeit with a stern eye watching him from not too far a distance.

As he narrates these anecdotes via voice note, he is in a car on the way to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, with his family.

Another benefit for Muslim football ticket holders is that they would be allowed to enter the kingdom to participate in the Umrah pilgrimage, without having to pay for a visa. It’s these acts of consideration that have provided comfort to Muslims during the tournament, giving them and their families an experience to cherish indefinitely.

Dalia Dallal, another avid football fan and one of Adnan’s friends, travelled to Qatar from the UAE during the tournament. Her experience from a safety perspective was unmatched, citing that on the first day, she accidentally left her passport in the restroom, and within minutes a Qatari official approached her to return it before she had even realised it was lost.

She also did not think she would ever attend a World Cup game. “I’ve always wanted to attend such tournaments, but male-dominated environments tend to make me feel uncomfortable. The Qatar world cup was a family-friendly tournament. I didn't witness a single fight or any form of harassment,” she reveals, alluding to the absence of alcohol in stadiums as being pivotal to encouraging a safe environment.

Western mainstream media had attempted to cast a dark shadow over the World Cup 2022 in Qatar. Nevertheless, from within, the light emerged and showed the world how capable the Arabs were of hosting the world’s most prestigious sporting event. Long may the lessons of this event's openness and safeguarding aspects show other sports federations and governments that this sport is open to everyone… Men, women and children, from all over the world.

Saoud Khalaf is a British-born Iraqi filmmaker and writer based in London. His videos, which have garnered millions of views across social media, focus on social justice for marginalised groups with specific attention on the Middle East. His latest documentary premiered at the Southbank Centre for Refugee Week.

Follow him on Twitter: @saoudkhalaf_

![For Adnan, who is Palestinian, attending the World Cup in Qatar and seeing the wave of support for the Palestinian cause was a dream come true [photo credit: Adnan Barq]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2023-01/Adnan.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=6d1lzqLf)